The first medical evacuation in the history of the International Space Station (ISS) is happening today.

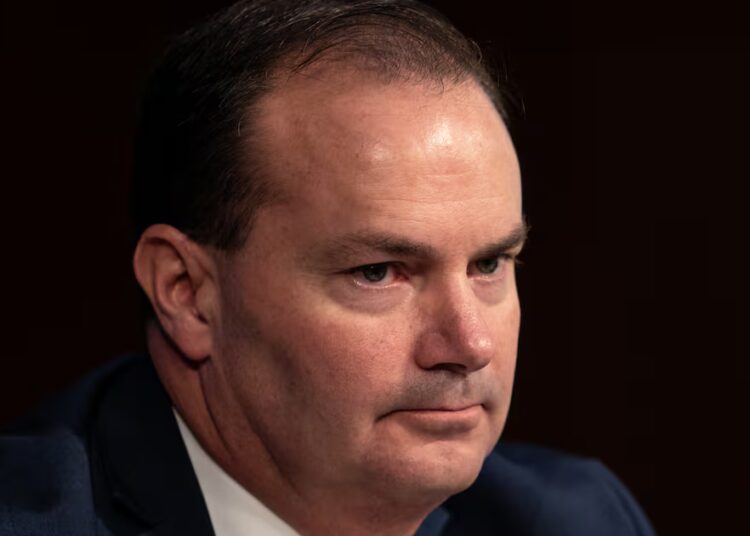

Crew-11 will return to Earth ahead of schedule because of an unspecified medical issue. Included in the group are NASA astronauts Mike Fincke and Zena Cardman, Russian cosmonaut Oleg Platonov, and Japanese astronaut Kimiya Yui. NASA didn’t specify what the exact condition was or which astronaut was dealing with an issue, citing privacy concerns, but indicated that the person’s condition is stable.

The reason why the whole crew must return home (and in the SpaceX capsule they came from) is because there are no spare crew-ready capsules at the moment, and NASA wants to avoid leaving astronauts in orbit without a way back. Crew-11, which left for the ISS in August, was nearing the end of its sixth-month mission anyways, making the call a bit simpler.

The ISS, which originally launched in 1998, has been continuously occupied by rotating crews of astronauts since late 2000, and it serves as an important international laboratory for developing new technologies and medicines, as well as studying life in the space environment. However, Crew-11’s departure doesn’t mean the ISS will be empty; it will be staffed by a skeleton crew of three until Crew-12 arrives in mid-February.

NASA’s chief health and medical officer James Polk said that the medical issue was not an injury sustained while performing work on the ISS but, rather, a health concern arising in the microgravity environment.

“Everyone on board is stable, safe, and well-cared for,” Fincke wrote in a LinkedIn post from the ISS. “This was a deliberate decision to allow the right medical evaluations to happen on the ground, where the full range of diagnostic capability exists. It’s the right call, even if it’s a bit bittersweet.”

This is also the first time in NASA’s history that a mission has ended early because of a medical issue. It’s not the first time ever; the Soviets performed two medical evacuations for cosmonauts in the 1980s. According to Polk, statistical models suggest that there should be a medical evacuation from the ISS about every three years, but it’s been smooth sailing for the past quarter-century.

“It’s almost amazing that we’ve maintained the ISS for [almost] 26 years constantly crewed without something like this happening before,” Jordan Bimm, a historian of US space exploration at the University of Chicago, told Scientific American.

Medical evacuations have been kept to a minimum, likely in part because all astronauts receive medical training and have access to telemedicine services on the ground. Several medical issues that arose in-orbit have been dealt with appropriately; no evacuation was required. One astronaut who developed a blood clot on the ISS, for example, was successfully treated with blood thinners. It’s a great reminder as to why innovations in the field of space medicine are so important. As more and more people leave for space, we’ll have to figure out how to treat them without requiring a return trip back to Earth.

Why space medicine matters

Space is obviously tough on the body.

In the microgravity environment — like one you would find on the ISS — astronauts face greater risks of early-onset osteoporosis, insulin resistance, and significant muscle loss. And without normal gravity exerting its pull on the body, blood, and other bodily fluids shift “up” toward the head, reducing the volume of blood circulating through the heart and blood vessels. The heart slacks off, becoming rounder. Cardiac muscles that normally work to constrict blood vessels atrophy on the ISS, and these changes become more pronounced over time.

Pressure changes and fluid shifts in microgravity can lead to spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome, which causes swelling and changes to the shape of the eye and brain. It can make astronauts’ famously 20/20 vision blurry. The longer astronauts are in space, the more likely they are to experience symptoms. While these changes (usually) revert when astronauts return to Earth, they could be more permanent in some people. And in the long-term, exposure to space radiation is linked to developing cancer and degenerative diseases.

All this sounds pretty grim if you want to spend the long stretches in space that would enable us to travel to Mars for scientific research or establish permanent off-world human settlements. But it’s not all bad news. Space medicine works to safeguard human health in the space environment, and it has tremendous benefits for the rest of us here at home.

Last year, I reported on space medicine and its promise to transform health on Earth. Haig Aintablian, the director of the UCLA Space Medicine Program, told me that one of the next big things in the field “is probably going to be the development of radiation protection mechanisms. I do believe that with the amount of emphasis being placed on radiation protection, we’re going to figure out ways to actually protect against significant amounts of radiation for the general public for multiple uses.”

AI could also act as a resource for the on-board flight surgeon, he predicted. It’s not so far off; Google collaborated with NASA to develop an AI system that could guide astronauts through diagnosing and treating medical ailments that arise in-flight, which could improve off-planet (and thus potentially on-planet) diagnostic capabilities.

In terms of this evacuation, “this seems abnormal now, but it is a preview of what will be the new normal if humans go to space in greater numbers,” Bimm told Scientific American. “People will get sick, and sometimes contingencies will have to be exercised.”

NASA will livestream the departure of the capsule starting at 4:45 pm ET Wednesday. Crew-11 is expected to land in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California early Thursday morning at around 3:40 am ET. You can watch live coverage on NASA+, Amazon Prime, and the agency’s YouTube channel.

The post NASA’s first medical evacuation is here. It won’t be the last. appeared first on Vox.