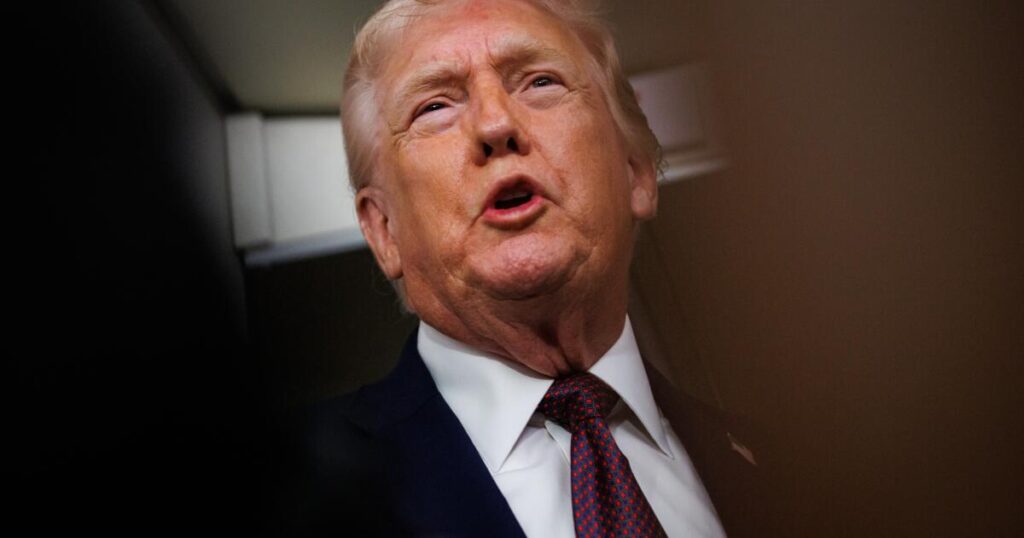

A decade ago, a famous and successful investor told me that “integrity lowers the cost of capital.” We were talking about Donald Trump at the time, and this Wall Street wizard was explaining why then-candidate Trump had so much trouble borrowing money from domestic capital markets. His point was that the people who knew Trump best had been screwed, cheated or misled by him so many times, they didn’t think he was a good credit risk. If you’re honest and straightforward in business, my friend explained, you earn trust and that trust has real value.

I think about that point often. But never more so than in the last few weeks.

In all of the debates about foreign policy — where people throw around terms like realism, internationalism, isolationism, nationalism, this ism, that ism — one word tends to draw eyerolls from ideologues: “honor.” Specifically national honor.

President Trump and many of his admirers believe he’s “restoring” America’s reputation on the world stage. Trump himself often says that we’ve “never been more respected.” It’s never exactly clear what he bases this on, aside from what foreign leaders purportedly tell him in private. Public opinion surveys are at best a mixed bag.

The deeper confusion is about what he means by “respect.” From the way Trump talks about geopolitics, it’s clear he equates “respect” with a Machiavellian mix of “fear,” “strength” or “power.” That is one definition. For instance, many people respect China as an economic and military power. But such respect is not synonymous with “admiration.” Everyone respects North Korea as a nuclear power. But few non-deranged people admire the Hermit Kingdom in any other way.

What’s missing is the concept of honor. One of the great critiques of the idea that economics is everything — that we are all mere homo economicus, maximizing income to the exclusion of all else — is that people value other things: love, family, morality, integrity, faith and, yes, honor. Trump’s theory of geopolitics could be described as patria economicus (though Latin purists might object). It’s a kind of realism that simply says the nation-state should do whatever it can to get the best deals for itself (or for the Homo Economicus in Chief).

This seems to be what Trump’s getting at when he says the only thing that can constrain him on the international stage is “my own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.”

His aide, Stephen Miller, insists that “the real world” is “governed by strength … is governed by force … is governed by power. These are the iron laws of the world that have existed since the beginning of time.” According to this logic, we can take Greenland from Denmark — and the Greenlanders themselves — because we can. The only question is whether it will be “the easy way” or “the hard way,” as Trump recently said.

We should acknowledge the truth of this. Put aside questions of law, the Constitution or policy. It’s true we could take Greenland militarily, gangster-style. It’s also true that I can take a gun and rob my friends. Again, legality aside, the question I have is, “would that be honorable?” In Trump’s terms, the seizure of Greenland would make us more “respected,” but it would not make us more honored. We would be betraying our allies (and ideals), and not just Denmark but all of NATO, by breaking our word. For what? Territory. Territory we have every right to use by treaty already. Would we be prouder of our military once it became an instrument of mercenary conquest?

St. Augustine once asked, “Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies?” George Washington was passionate about notions of honor and virtue. In his farewell address, he insisted that we should honor our commitments “with perfect good faith.”

An America that honors its commitments has allies who will honor theirs. An America that betrays her commitments by force or by the threat of force will find the cost of political capital exorbitantly expensive at the earliest opportunity.

The administration reads the Monroe Doctrine as a warrant for the president to do as he likes on his turf and, in Trump’s mind, Greenland is our turf. That is not how President Monroe saw things. In his first inaugural, Monroe declared, “National honor is national property of the highest value. The sentiment in the mind of every citizen is national strength. It ought therefore to be cherished.”

Most Americans are right to want their country to be powerful. But they should also want our country to be good. Aristotle believed that true honor is reserved not just for power or glory, but virtue. Those who prize virtue will find little comfort in Trump’s assurance that he is only constrained by his own morality.

The post Trump isn’t interested in being honorable — he’d rather be feared appeared first on Los Angeles Times.