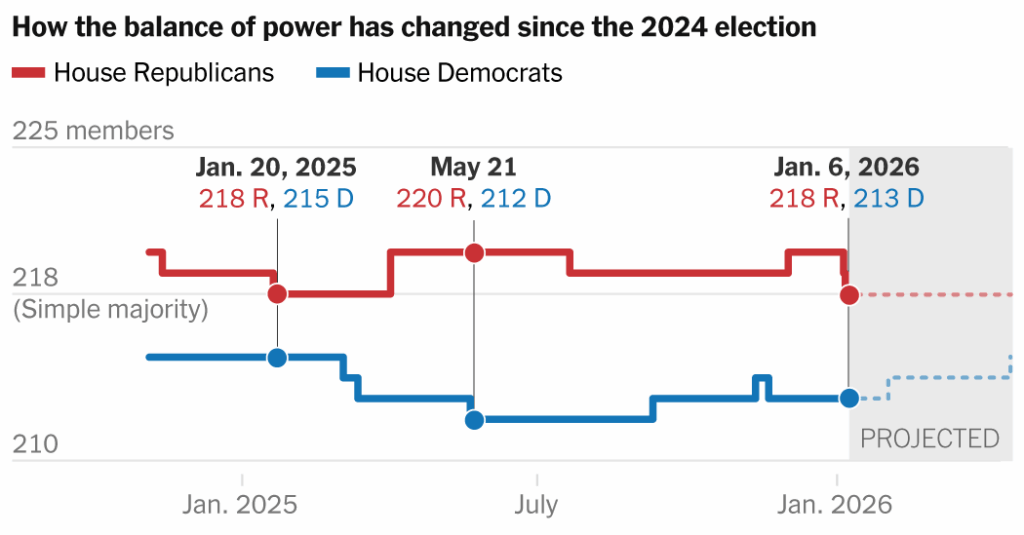

A surprise resignation and a sudden death have left House Republican leaders starting the new session of Congress with their already slim majority down to the bare minimum of 218 seats.

Speaker Mike Johnson is now able to afford just two defections on any party-line vote if all members are present — and in an election year, they seldom are. In the coming weeks, his situation is expected to become worse, whittling down the margin to a single vote.

It is the continuation of a dynamic that has plagued House Republicans since President Trump took office in 2025: A majority so small that it gives outsize power to any one member who wants to buck the party. It makes governing difficult, if not impossible.

When Republicans cemented control of the House in the 2024 elections, they did so with only a small edge over Democrats: Republicans held 220 seats compared with 215 for the Democrats. They could afford only two defections to still pass legislation.

After the resignation late last year of Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, Republican of Georgia, and the sudden deathlast week of Representative Doug LaMalfa, Republican of California, the current breakdown is 218 Republicans to 213 Democrats.

The edge is likely to dwindle further after a special election later this month in Texas to replace Representative Sylvester Turner, a Democrat who died last March. Democrats are expected to pick up an additional seat there, bringing their total to 214. At that point, Mr. Johnson would be able to afford only one defection on a party-line vote and still pass legislation.

An election on April 16 in New Jersey to fill the seat of former Representative Mikie Sherrill, a Democrat who was elected governor, is expected to provide Republicans no relief. The solidly blue district is expected to remain in Democratic hands, nudging the party breakdown to 218 Republicans and 215 Democrats, still a one-vote margin for the G.O.P.

Most major legislation cannot even come to the floor without a House vote to set the ground rules for debate. Without a working majority, Republicans effectively have no control over the floor and no ability to move their agenda.

And under House rules, a tie vote fails.

The result of it all has been a historically unproductive session of Congress so far: The House set a grim record in 2025, casting the fewest votes of the 21st century during the first session of a two-year Congress.

It’s worth noting that Mr. Johnson has discretion over when he swears in a new member of the House. He waited seven weeks to do so after Representative Adelita Grijalva, Democrat of Arizona, won her seat in a special election, claiming he could not seat her while the House was out of session. (There is no such rule.)

But Mr. Johnson’s one-vote margin is often not enough when he has to contend with Representative Thomas Massie, Republican of Kentucky, who often breaks with his party on key votes and has been so impervious to pressure that Republican leaders and Mr. Trump himself no longer bother to whip his vote.

The tight margins mean that attendance will be a critical and continuing issue on both sides of the aisle — especially in an election year when many House members are running for statewide offices and have turned their attention away from Washington and toward meeting potential constituents at home.

And they have rendered Mr. Johnson’s weak grip on a demoralized House Republican conference even weaker as the party looks anxiously toward midterm elections in which their control of the chamber is at stake.

“A lot of times they’ll say, ‘I wish Mike were tougher’ — he’s tough,” Mr. Trump said while addressing House Republicans last week at a party retreat at the Kennedy Center. “But you can’t be tough when you have a majority of three — and now, sadly, a little bit less than that.”

Ashley Wu is a graphics reporter for The Times who uses data and visuals to help explain complex topics.

The post The House Republican Majority Is Down to Almost Nothing appeared first on New York Times.