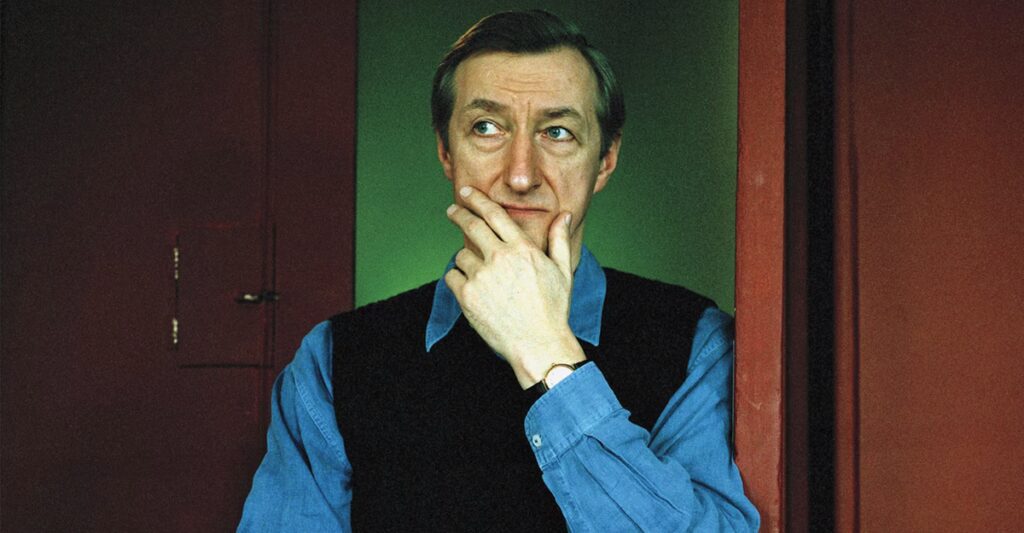

“Yes—oh, dear, yes—the novel tells a story,” E. M. Forster wrote. “I wish that it was not so.” Julian Barnes has confessed that as a young man reading Aspects of the Novel, he found this sentiment “feeble” and responded impatiently, “If you aren’t up to telling a story, why write a novel?” Barnes, who turned 80 in January, now sings a different tune, and anyway, Forster’s wish was long ago granted. The literary novel of today is quite free from conventional storytelling, and ironically (irony is one of his specialties), Barnes got busy loosening the bonds early in his career. He’s still at it: His brief new novel, Departure(s), offers only a sketchy storyline, mixed with memoir and thoughts on memory. An extended farewell, an author’s valedictory flourish, the whole package is a culmination of sorts, shimmering with his silky, erudite prose; beneath the suave surface is an earnest investigation into the mysterious ways of the human heart.

The scant plot in Departure(s)—a “true story” the narrator swore he wouldn’t tell—tracks the two-part romance of Stephen and Jean, friends of his at university who fell in love, broke up when they graduated, then connected again in late middle age after Stephen asked Julian to reach out to Jean. Like many of Barnes’s 14 previous novels—including his most famous, Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), and the Man Booker Prize winner, The Sense of an Ending (2011)—Departure(s) tells a love story filtered through the consciousness of a ruminative, standoffish man preoccupied with something other than the love at stake.

In the earlier novels, Barnes is given a fictional identity; in the new one, the author speaks to us directly, blithely confident that a skeptical realist with a restless mind probing familiar yet essential experiences—how the brain works, what happens as we age—is all the entertainment we require. He shrugs off the romance: “Couple fail to make one another happy, well, turn the page.” But one should never disregard the way love works (or doesn’t) in his books. In the words of Philip Larkin (a Barnes favorite), love is the “element / That spreads through other lives like a tree / And sways them on in a sort of sense.”

When love is absent, bottled up, interrupted, or misdirected, Barnes is at his best. One-tenth of Flaubert’s Parrot is heartache, but it’s buried under the other nine-tenths, a rambling miscellany of Flaubert factoids. The novel reads at times like an eccentric biographical essay, at times like a cranky compendium of pet peeves. Yet the reader is peripherally aware that the narrator, Geoffrey Braithwaite, indulges his literary obsession so as to distract himself (and us) from the tragedy of his wife’s death. After dragging his feet for most of the book, he at last addresses his loss, his despair, in a short chapter called “Pure Story.” A melancholy emotional logic holds Flaubert’s Parrot together, not least the parallels between the unfaithful Ellen Braithwaite and Emma Bovary, whose name is synonymous with adulterous passion.

Geoffrey warns against the smug certainty of those who think that by trawling for facts they can catch the essence of a life, whether Flaubert’s or Ellen’s. (“My wife: someone I feel I understand less well than a foreign writer dead for a hundred years.”) In an oft-quoted passage, he considers a fishing net with Olympian detachment:

You can define a net in one of two ways, depending on your point of view. Normally, you would say that it is a meshed instrument designed to catch fish. But you could, with no great injury to logic, reverse the image and define a net as a jocular lexicographer once did: he called it a collection of holes tied together with string.

He adds, “You can do the same with a biography.” You can do the same with a novel.

Once you start looking for holes in Barnes’s books, they open up everywhere: what’s unknown, withheld, or willfully ignored. Absence itself—absence of love, absence of the beloved—becomes a crucial locus of meaning. In Flaubert’s Parrot, for instance, the longer Geoffrey delays telling us about Ellen, the more we sense how much she meant to him. In Departure(s), there’s a 40-year gap between the first time Stephen and Jean try to love each other (which a young, love-starved Barnes experienced as “romanticism-by-proxy”) and the second, “rekindled” attempt, reluctantly facilitated by Barnes. Both Stephen and Jean tell him, “This will be my last chance of happiness.” They marry—a church wedding!—and then break up for good. A decade or so later, they’re both dead. Breaking his vow, Barnes writes about them, exposing Stephen as a spurned romantic and Jean as incapable of accepting or returning his love. Barnes says it’s what he’s been after “all my writing life: the whole story.”

The whole /hole pun is surely intended. The brief, truncated narrative leaves Barnes space to ruminate on the blanks in our memory. He glides past a truism (“As we age, forgotten memories of childhood often return to us”) and delivers a startling prognosis: “At the same time, our grasp of the middle years decays. This hasn’t happened to me yet, but I can imagine how it might develop as senescence takes hold.” In other words, he adds, if we live long enough, our lives—his, mine, yours—may be reduced (like Stephen’s and Jean’s) “to a story with a large hole in the middle.” Meanwhile, scattered references point to the defining event of those four missing decades, at least in Barnes’s own life: In 1979, he married Pat Kavanagh, a literary agent six years his senior; three decades later she died, just weeks after being diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor.

In 2013, he published Levels of Life, a celebration of his love for her and an anatomy of his mourning. “I was thirty-two when we met, sixty-two when she died. The heart of my life; the life of my heart.” An essay, a short story, and a memoir squeezed together in one slim volume, the book defies formal categorization, but the sum of those disparate parts is an achingly honest dirge:

It’s true that some of my grief is self-directed—look what I have lost, look how my life has been diminished—but it is more, much more, and has been from the beginning, about her: look what she has lost, now that she has lost life.

Her absence imposes a very specific form of loneliness—“not so much loneliness as her-lessness.”

He broods about memory and aging in Departure(s), of course he does: He has a new partner, Rachel, who’s 18 years his junior. He reveals as well that he was diagnosed in 2020 with a rare blood cancer that can be managed with a daily dose of chemo, but not cured. Before he knew his cancer wouldn’t kill him, he began making notes for what he thought would be his final book, to which he gave a provisional, “archly self-pitying” title: Jules Was. He is “heavily afraid,” according to one note, of the grief his demise will “impose on R”—a replay, perhaps, of what he himself experienced.

[Read: It’s hard to change your mind. Julian Barnes’s new book asks if you should even try.]

Setting aside the pain of Kavanagh’s death, almost 20 years ago now, Barnes acknowledges the luck of his life, particularly his professional success. The oldest in the all-male scrum of his generation’s celebrated British novelists (Martin Amis, Kazuo Ishiguro, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie), he has enjoyed a prize-strewn career. And he has had happy second chances, unlike the unfortunate Stephen and Jean, and unlike Tony Webster, the narrator of The Sense of an Ending, the first book Barnes published after Kavanagh died.

Tony, too, is offered the opportunity to rekindle an old flame. Again, there’s a 40-year gap. A solitary divorced retiree who puzzles over familiar Barnesian preoccupations (time, memory, aging), Tony comes into contact with an ex-girlfriend, Veronica. He can’t let go of their backstory. Soon after they split, she took up with one of his close friends—who shortly thereafter killed himself. Now Tony tries to make sense of two endings: the breakup and the friend’s suicide. But instead of a rekindling, or even a moment of clarity, he’s left with a muddle. “You just don’t get it,” Veronica tells him. “But then you never did.”

“Our life is not our life,” Tony tells himself, “merely the story we have told about our life.” He acknowledges that his own is utterly bland: his career, unspecified; his marriage, tepid; his daughter, emotionally distant. “What did I know of life,” he asks, “I who had lived so carefully? Who had neither won nor lost, but just let life happen to him?” The romance, the life-and-death passion in this sad, sad novel, takes place out of sight, its contours unknown—except that, of course, none of it involves poor Tony, who gradually then suddenly becomes aware of what’s missing. Barnes wrings emotion—sharp, sustained anguish—from remorse at love’s absence.

Even in his nonfiction, Barnes points to the holes all around us. In Nothing to Be Frightened Of (2008), a sophisticated, meandering meditation on mortality and his own timor mortis (published, coincidentally, a few months before Kavanagh’s death), he keeps the “nothing” of death front and center. And in The Man in the Red Coat (2019), a boldly unconventional biography of Samuel Pozzi, a pioneering French gynecologist who was a lifelong friend and sometime lover of the immortal Sarah Bernhardt, Barnes repeatedly taunts us with the limits of our knowledge: “We cannot know.”

What is the string that binds the holes in a biography or a novel? Memory, yes: “We all know that memory is identity,” Barnes writes in Departure(s); “take away memory and what do we have?” Yet he also reminds us that memory is the “place where degradation and embellishment overlap.” To compensate for degradation and to make embellishment pleasing, we call upon imagination and style (that erudite prose), and the comforting continuities of narrative. Add to all of that a kind of attentive engagement—Barnes prefers a more active word, “attending,” a knack for noticing details that beg to be preserved—and you might manage to knit together a coherent pattern of events and images, a history. You might even give shape to a love story. “Writers believe in the patterns their words make,” he tells us in Levels of Life. “We cannot, I think, survive without such belief.”

The big-picture pattern that emerges from Barnes’s shelf of books is the mystery of love, which he addresses directly in 20-odd pages of A History of the World in 10½ Chapters(1989), an early book of linked stories. The half chapter, aptly named “Parenthesis,” has achieved a modest cult following, undoubtedly because of passages as clever and un-saccharine as this one:

“I love you.” Subject, verb, object: the unadorned, impregnable sentence. The subject is a short word, implying the self-effacement of the lover. The verb is longer but unambiguous, a demonstrative moment as the tongue flicks anxiously away from the palate to release the vowel. The object, like the subject, has no consonants, and is attained by pushing the lips forward as if for a kiss.

In the same unsentimental vein, he insists that we must be “precise” about love, by which he means, “attending to the heart, its pulses, its certainties, its truth, its power—and its imperfections.” That’s a good description of the task that Barnes has taken on as a writer. A final admonition: “We must believe in love, just as we must believe in free will and objective truth.”

At the beginning of Departure(s), Barnes tries out a new perspective. He’s fascinated by an extreme form of what’s known as involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), in which a particular action triggers a cascade of memories of all the times that action has been performed in the past. Here’s an example: What if saying “I love you,” whether you meant it or not, triggered an IAM? He asks, “How would you face the record—the chronological record—of all your lies, hypocrisies, cruelties?” What if one sexual fantasy triggered an IAM onslaught, including all the “inadmissible, sluttish adulteries of the heart which we have chosen to suppress”?

There are memories we suppress and then there’s the echoing emptiness of everything we’ve simply forgotten, a vanished immensity, the selves we’ve left behind, the many millions of skin cells our body sloughs off every day. Faced with the choice of string or hole—a relentless deluge of recovered memory or the pathos of forgetting, of shedding thoughts that seemed momentous a moment ago—which would you choose?

At the end of Departure(s), Barnes announces, “This will definitely be my last book—my official departure,” and he imagines a “final conversation,” conjuring the image of

writer and reader on a cafe pavement in some unidentified town in some unidentified country. Warm weather and a cool drink in front of us. Side by side, we look out at the many and varied expressions of life that pass in front of us. We watch and muse.

“What do you make of that couple,” he asks us: “married, or having an affair?” Spotting an old couple holding hands, he says, “that always gets to me.” He offers other observations, “ordinary, conversational mutterings.” He sees, out of the corner of his eye, that we share his “attendingness.” He rests his hand on our forearm—a brief touch—and slips away. His parting injunction: “No, don’t stop looking.”

This article appears in the February 2026 print edition with the headline “Sense of an Ending.”

The post Sense of an Ending appeared first on The Atlantic.