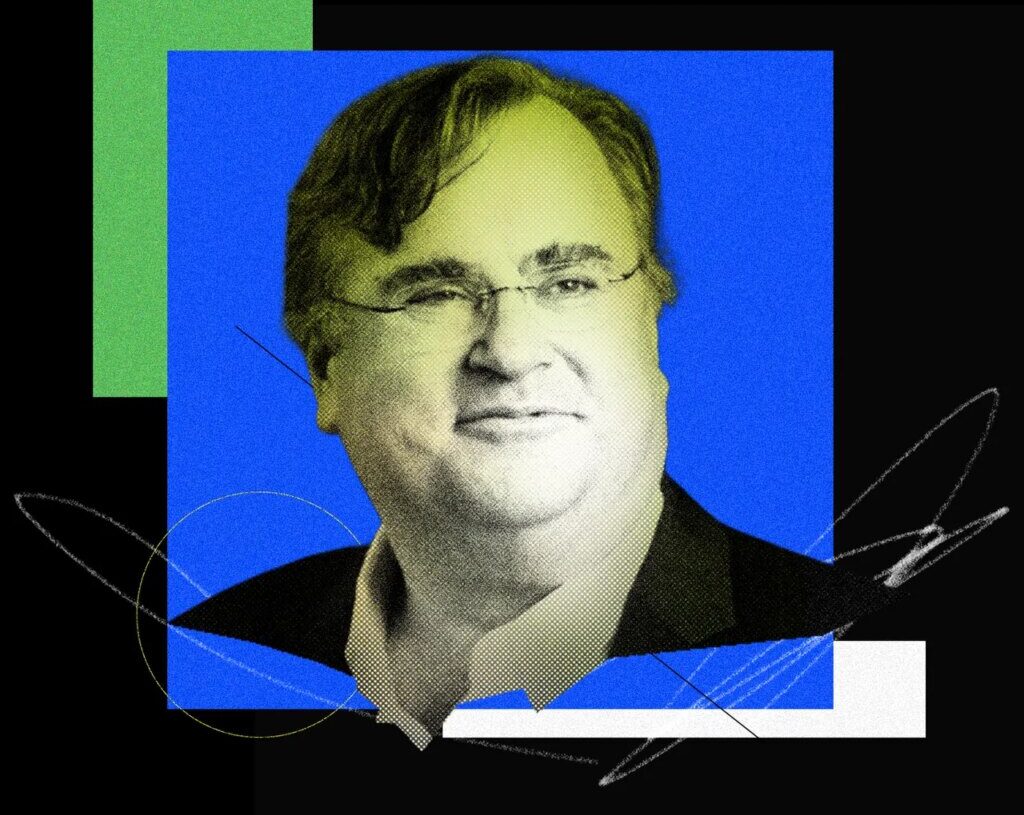

Reid Hoffman doesn’t do much in half measures. He cofounded LinkedIn, of course, and helped bankroll companies including Meta and Airbnb in their startup days. He has also fashioned himself, via books, podcasts, and other public appearances, as something of a public intellectual—a pro-capitalist philosopher who still insists that tech can be a force for good.

Most recently, Hoffman has emerged as one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent defenders of artificial intelligence. His newest book, 2025’s Superagency, makes the case that AI won’t diminish human capacity but will instead amplify it. In our conversation for this week’s episode of The Big Interview, Hoffman readily riffed on AI’s utility for pretty much everything, whether you’re looking for a research assistant or a second opinion on your blood work. Hoffman even relied on AI to make one of the most unconventional—and perhaps uncomfortable, depending on your view of AI-generated creativity—Christmas gifts I’ve heard of lately. (And no, he didn’t get me one.)

Whatever you think of Hoffman’s utopian views on AI, credit where due: He’s also a very outspoken critic of President Trump—a rare trait in a tech world that’s grown increasingly quiet, or cozy, when it comes to the cruelties of the US administration. Hoffman’s overt political views haven’t been without consequence: Trump has twice threatened to launch investigations into him, most recently calling on Attorney General Pam Bondi to dig into Hoffman’s ties to Jeffrey Epstein. (In 2019, Hoffman apologized for his mid-2010s relationship with Epstein, which he says related solely to fundraising for MIT. He has subsequently called for the government to release the Epstein files in full.)

Despite those threats, Hoffman isn’t pulling punches: When we sat down to tape this episode in mid-December, he readily called out the administration for degrading American government, criticized his peers for keeping their heads down, and urged Silicon Valley to stop pretending that neutrality is a virtue. If only more billionaires were saying it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KATIE DRUMMOND: Reid Hoffman, welcome to The Big Interview. So glad to have you here.

REID HOFFMAN: I’m glad to be here.

We like to start these conversations with some very fast questions. Little warm-up. Are you ready?

Great!

Voice memo or text message?

Text message.

Cooperative games or competitive games?

Cooperative games.

The biggest difference between you and Elon Musk?

Sanity.

What’s the hardest lesson you’ve ever had to learn?

Oh gosh, there’s a whole lot. Probably when to give up.

Who do you wish would run for president in 2028?

Sanity.

Sanity for president.

Yes, exactly. You know, it’s funny, I probably can’t give a good answer to that question. I mean, the people I would want to run for president probably won’t.

Oh, that’s too bad.

Yes.

You can’t say their names?

Since I’ve tried to persuade them to do so, I think it’s probably impolite.

I’m fascinated. Next time we talk, I’m going to force you to tell me. What is your one, personal, killer use case for AI?

Well, I just generated a holiday Christmas album as my Christmas gift for all my friends.

I assume they all know that it’s AI generated music?

Yes. And it’s on records. We put it on records.

So it’s from your heart into the AI …

Yes.

… to their Christmas tree.

I’ve always had this desire to have Christmas music that has irony as well as affection for the holiday. So, there’s a song on ugly sweaters and, you know, all of this kinda stuff. As opposed to the “holly, jolly Christmas,” you know, something that actually has some humor. Almost like what “Weird Al” Yankovic would do if he was doing a Christmas album.

Is that what you told the AI to do?

Yes, exactly. It’s completely AI-generated. Actually, we did one model for the lyrics and another for generating the music and everything else to try to get the best of all things. By the way, it’s stunning. My better half was listening to this and going, “Wait, that’s not an actual singer?” I’m like, “Nope.”

Coming soon to WIRED: a leaked copy of Reid Hoffman’s AI-generated holiday album.

Oh, I’m happy to send you it.

What is most exciting to you about 2026?

Well, there’s a lot, but I would say primarily the amazement that we’ll get with AI. So it’s not just like Manas AI and trying to cure cancer through drug discovery, but also the Superagency book, and how it’s giving us super powers. Obviously there’s some things that are overhyped and won’t be here soon, but what is there is amazing, and I think that’s probably the most exciting thing, and maybe that’s, unfortunately, too generic of an answer.

We’ll get into AI in just a minute, but let me ask you one last question. You went to a private school where students did farm chores. I learned this about you getting ready for this show. Which was your favorite?

Well, the hardest one was called Winter Barn, which is you got up at 5 in the morning in Vermont and you trekked across the very cold hillscape and you shoveled manure from behind cows. So that was a grit and endurance test. And probably my favorite was actually driving oxen through the woods as part of the maple syrup farming.

That brings me to where I want to start. You were born in Palo Alto, right? You secretly applied to boarding schools for high school, which, now having a young daughter, I can’t even imagine how I would react to that. You ended up at The Putney School in Vermont, a progressive high school, working on a farm, and you’ve said it really set you up in a big way. Tell us about that.

Putney is very unique, and part of the uniqueness is its theory of education as preparing you as a person. Most of these schools are all college prep, and you will have the right academics to prepare you for Stanford, Harvard, Yale, whatever, blah, blah, blah, blah. Putney’s like, no, we try to create well-rounded people. You have a work job, even if you’re paying full tuition. Every quarter, you must do some art. You have evening activities; I did blacksmithing, there’s woodworking and poetry-writing and helping construct the magazine.

As part of each quarter you do a serious project, which is something you create. You break twice a year and go into various wilderness expeditions together. So I did canoeing and other kinds of things as part of this. And that full, rounded person is part of what I think is the gift that Putney gave me.

Now, it meant that when I started at Stanford, I was actually behind many of my friends and fellow students on actually learning academics. I had to learn because I hadn’t done academics as intensively, and I had to learn much more intensively in my first year on that. I took advantage of a bunch of different things that Stanford had to offer. It was like, Oh, well, I’m doing this really intense math course, I’ll get a tutor in order to kind of process these things.

That was essentially the setup. It gave you a kind of entrepreneurial thinking, because you weren’t just like a cookie cutter, you know, learn the physics …

Take the SATs, test into a good college.

Exactly. It was a much broader spectrum, and so that helped me in thinking in a much broader spectrum and also helped me as a person getting ready for stuff.

One thing that’s interesting to me is that you went to Oxford. You thought you may want to be an academic philosopher. Obviously, you did not do that. You decided to go into tech. Funnily enough, I also thought I might want to be an academic philosopher. I got a bachelor’s in philosophy. Then I decided not to get a master’s degree because I remember feeling like I didn’t want to be sitting on a university campus for the next 40 years of my life.

But it did, I think, set me up very nicely for the career that I have now in ways that people might find unexpected. I’m curious for you, why did you make the move that you did? Why did you turn your back on academic philosophy, and what do you think that interest and that pursuit of philosophy gave you in the long term?

At Stanford, I did artificial intelligence, cognitive science, and this major called small systems. I was like, “We don’t understand what thinking and language is, so maybe philosophy does.” I went to Oxford, studied philosophy to possibly do that, and part of my interest has always been human beings. How do we understand, you know, the world, each other, ourselves?

It’s helped in a lot of ways. So it’s helped in entrepreneurship. Part of what entrepreneurship is, is thinking about what the world might possibly be. This new product, this new service in a market with competitors and so forth, and thinking about that in a crisp way.

One of the things that I tell entrepreneurs, especially consumer internet entrepreneurs, is that they absolutely should have a theory of human nature. When you’re creating a product that you hope to have a billion active users of, the way that that happens is you have a theory of human nature. Now, back in 2002, when I was trying to give talks at business schools and I was trying to wake them up on things, they would say, “Well, what’s your secret of investing?” And they were expecting I would say, “Well, I analyze the customer acquisition cost, long-term value …” And I was like, “I invest in one or more of the seven deadly sins.”

Is that true?

Yes. It’s a theory of human nature. Now, one of the things I’ve later updated is, yes, I invest in the seven deadly sins with the hope to transform them into human positivity.

When I was giving this talk, I think at Stanford in 2006 or something, someone said, “Well, what’s Twitter?” And I said, “It’s identity.” I misunderstood it. It’s wrath. We have these deep psychological things, and you want to evolve them to our better selves. Someone said, “What’s LinkedIn?” It’s greed. But, of course, part of LinkedIn is trying to have your best economic amplification through working with the people you know and have worked with. That’s the goal with LinkedIn; it isn’t to sit around and be King Midas.

To think about these as human products, as ways of changing and evolving the human condition. Philosophy is very helpful for that.

Speaking of the human condition, I want to move us into AI. You are very open about being optimistic about artificial intelligence. Your latest book, Superagency, argues that AI is not replacing human agency, right? It is multiplying it. It is an intelligence multiplier. That’s what you say. Give us a quick overview of how you got to that argument and exactly what you mean there.

So the first thing is: AI is not a naturally occurring phenomenon. We can shape it. Part of Superagency was bringing together what people were concerned about, which is the loss of agency, loss of control, loss of privacy, loss of economic engagement, et cetera, et cetera.

Then, obviously, you have the existential risk people, you know, loss of life or something else’s ways of doing this. If you look at this in the history of technology, including the printing press, including electricity, this argument has come up each time as this kind of loss of agency, and we’ve shaped it to much more positive agency. So the whole thing is, as technologists, we should be shaping it to positive agency.

If you put something serious on the line and say, “Compose a Christmas album,” I would be dead. Right? There’s no way I could do that, but I can do that with AI. It’s kind of a superpower. I, of course, also use it for research and use it for, you know, amplifying my thinking and solving the blank pages and all the rest. But we get all these superpowers. One of the superpowers I recommend everybody to use frontier models for is for both doctors and patients. Any serious medical thing you have, use your choice of frontier model: ChatGPT, Copilot, Claude, Gemini, whatever, as a second opinion. Right? Like that’s a superpower.

I would vastly prefer for my doctor to handle that. The idea of having more medical information, for me personally, is terrifying. But maybe for someone else it would be a superpower.

But, by the way, I’ve had friends that do this: You get your blood tests and literally take a picture of the blood test, upload it to ChatGPT, and then have a conversation and get a dialog. It makes it much more interpretable and understandable. Then you can say, “Well, I’m worried about this thing that’s showing up in red. Why is that? What does that mean, and what can I do about that? Should I take the blood test again?” This kind of stuff. You can already see it as an amplifier.

My push for people is if you are not using AI in a way today that isn’t seriously helpful to you, you are not actually trying hard enough. Right? It doesn’t mean that it does everything. For example, as an investor you can’t say, “Make my investment decisions.” But you can say, “Give me the due diligence list on this.” It works very well.

Now, of course it’ll transform jobs, and there’ll be a bunch of pain in that transformation. But the way that you as an individual can avoid that is to be engaged; it’s the best learning technology created in human history. It’s better than the book. So use it in order to do that and as part of adapting to the future.

That’s the essence of the argument, which is we’ve always had these concerns about agency when we have new technology. In every case so far, it’s led to an amplification of human agency. We are able to shape it as technologists and builders and iterate in order to do that. That’s what we should do.

One piece of that is this idea of the potential of this technology in the hands of billions of people, right? That’s a very powerful idea. The idea of democratizing access to education or access to health information—those are very, very powerful concepts. But the practical part of me can’t stop coming back to the idea that a lot has to happen for billions of people to have equitable access to technology. Do you worry that AI will concentrate that agency in the hands of fewer people, rather than distribute it? And how can that dynamic change?

Well, there’s two things. One, mass market technology does tend to have very broad access. So your Uber driver has the same iPhone as Tim Cook has, right? So when you get to very, very broad, it’s actually made the same for everybody. Like there isn’t a wealthy person’s cell phone. We all use the same cell phones now.

As far as we know.

Well, I think I might know, and I don’t. So I have a credible statement here. Then the second thing is that by having multiple companies competing really ferociously, they are doing the work to get it to hundreds of millions of people. Next year will be billions. And you know, the vast majority of ChatGPT is free usage. The vast majority of Gemini is free usage. That means if you have access to the internet, you have a phone, you have a library computer, it is actually broadly usable.

Now, we do have wealth differentials in society. I don’t know what society looks like without inequality. This is one of the things about the goal of equality; you want equality of opportunity and equality of talent engagement and so forth. But we run everything in society like there are people who compete for your job. There’s people who compete for my job. Few people get those jobs, but you want to have everyone have the opportunity. For example, today you already have these agents being amongst the best tutors that you could possibly get. If you just put it in as a meta prompt—“don’t give me the answer, walk me towards the answer”—you can actually have it as an educational tutor today.

I want to ask you about art. Listening to you talk about your early education and the idea of creating a whole person, you had this very multifaceted, very hands-on educational experience, and there is something so distinctly human about so much of that.

My mom was a poet, so I have the idea of my mother sitting down to write poetry as a craft. We are now talking about you using AI to create a Christmas record. I’m curious about how you grapple with the AI and art and creativity debate. Obviously, this is a very, very hot topic. Everybody has a different point of view on it, and it’s very fraught. Art is very emotional for a lot of people. It’s also their livelihood. How do you think about that?

I have no objections to someone who says art is something specifically created by humans, and you have to be using very old-school technology, like a paintbrush—that’s still technology, by the way—and that’s the only way that you can do this. I do have objections to people who say you’re not allowed to use new technology to make art.

By the way, we’ve had in quasi-recent times this idea of Oh, photography can’t be art. Only painting, because you learn the mechanics of doing this and so forth. So, you know, this debate has happened in various ways before.

I do think that AI is gonna transform a lot of art processes. I use AI intrinsically, for example, in writing books. People go, “Well, did you just give me a piece of writing that was completely, like, press a button and get it from AI? Or do you own it in some way? Did you shape it or craft it in some way?” Some people say, “I only wanna see things that have no AI touch.” And some people say, “I want to have it so that you actually typed every word, but you could be using AI as an editor.” I have the same views on art.

The technology will disrupt how movies are made. It will disrupt how music is made. People go, “Well, wait a minute. I put in all of this energy, and I got very specific in terms of a skillset in order to do this.” Now the skillset’s changing relative to output production, given the use of this tool. But I think that’s the nature of progress, and sure, it’s difficult in the short term, but it’s part of what’s really good.

How have you wrestled with AI’s acceleration versus its risks? I know that you have advocated for AI development to continue, not to be slowed down in unduly ways, but how do you think about the risk versus reward there?

If you said, “Hey, we’re not gonna put a car on the road until we answer every risk,” you’d never get a car on the road. You have to put the car on the road. You have to drive it, you have to learn it. And by the way, you’ll have some faults for that.

You invent the car, you invent the car accident. But what you do is you say, “What are the things you prevent in advance?” which are the limited subset of stuff that’s really pretty catastrophic. Like, no, you can’t have a car without a brake. You must put brakes in.

You do iterative deployment, you then go, “Oh, this is the thing we should fix, given what we’ve learned.” Some of it happens in the industry. Like, in the car, you add airbags. But some of it also happens through regulatory [measures]. Society goes, “I know there’s no consumer demand for seat belts, but we know what the hospital outcomes are. We’re gonna mandate seat belts.”

Well, sure. But how is the “mandating seat belts” part going in the AI regulation conversation?

Well, I’m not sure we’re—look, I think we’re just beginning to get to … I think one of the places that’s most interesting in it, which is do you have your chatbots talking to children? Yes/no. If you have your chatbots talking to children, are you responsible in the way that that one should be responsible to children? Like, for example, questions around self-harm or other kinds of things, and what does that look like?

I think Anthropic is doing a good job of showing the way of saying, “Hey, look, we need to be really proactive about cybersecurity because this could be used for all kinds of cybercrime, and we’re gonna be really proactive and everyone should be doing the kinds of stuff we’re doing.”

You know, I was on the board of OpenAI for a while, so looking at GPT-3, GPT-4, GPT-5 in sequence, the toolset for them being aligned to human values, to human well-being, got richer as the models got better.

So that’s the reason I’m broadly very positive. I fundamentally agreed with the Biden executive order on AI, which is, hey, have some transparency and reporting and a red-team plan and all the rest of the stuff. I think all that stuff is still gonna be there, despite the current administration’s let’s revoke everything that Biden possibly touched as totally bad and evil [stance], which is like a child’s response. You obviously should be like, that part was good, that part was bad as opposed to revoke it all. That is just, clearly, incorrect.

You are a Democrat. You have been very politically outspoken in recent years. Are you worried that your political point of view right now is denying you a seat at the table when it comes to AI and AI regulation? What are you doing to make sure that your voice is a prominent one as this regulatory framework either does or does not take shape under this administration?

Well, my view about my voice at the table is I only come to the table when asked and try to be helpful. If I was asked by the current administration to try to help with what they think, I would do that.

You have not been asked.

I have not been. Then they claim that the previous administration is the same and it’s very politically biased. I at least know that the previous administration would call people who disagreed with them and ask their point of view, minimally. What I try to do is do things like this: podcasts, media, writing books, advising people when they ask for advice.

I think part of what you try to do to contribute to society is you try to contribute your best possible work and perspectives and try to gather people around those to maximize the chance that it has an impact. That’s the best you can do.

You are a billionaire in politics, and you frame that engagement as a way to strengthen democracy. I’m curious about when that value became personal for you, when it felt like a personal imperative as opposed to an intellectual idea.

One of my criticisms about the underlying libertarianism in American culture is that I believe—call it Spider-Man ethics or Voltaire ethics—with power comes responsibility. If you make a bunch of money or you inherit a bunch of money, that’s an investment from society.

I’m a believer in the capitalist system. I’m a believer in the fact that we set out goals for people to contribute to society and then get rewarded from that. You know, all systems are imperfect. So it doesn’t mean it’s perfect, but you know that, as a broad-based system, it’s good. Now, that being said, I think with power, when you get power in one form, power is money. Another form of power is the media. Another form of power is government, and with that comes responsibility.

The responsibility is not just to yourself but to society and to humanity. I started serving on nonprofit boards very early in my career. If any government official asked me for something, I would try to help in terms of advice.

What I think we’re seeing is the general decay of the American government, and American society, through the current administration. At the beginning of [2024], I said, “Hey, I anticipate I’ll get political persecution, calls for the DOJ to investigate me from social media, Truth Social, et cetera.” But there’s also many different things. It’s like, you know, if you said, “Hey, we’re living in a society where masked people are pulling people off the streets and putting them in vans and putting them in something that can be characterized as a camp.” Those are degradations of society.

That’s the reason why with Trump’s [first] election I really started leaning in. Now I’m gonna try to work on society, because I think that’s one of the places where responsibility comes in for those who have power.

The narrative around Silicon Valley in the last year has not been politically generous, at least from the media, and I include WIRED in that assessment. Steven Levy wrote what I thought was a tremendous cover story for us several months ago about this.

I agree.

A lot of your peers have been very quiet about [all this], if not downright cozy, with the administration. How do you understand this change in Silicon Valley? How does it read and look to you?

Obviously it’s always a challenge when you say all Silicon Valley.

The media has a way with simplifying narratives.

Yeah. But let me break it down into some groups. The broad collective belief in Silicon Valley is that a super important way to make change in the world is building technology companies that build the next products and services at scale. It’s one of the levers that changes things.

Arguments for that are like what I’m doing with Manas AI in terms of trying to cure cancer and so forth. That’s a religion that I think everyone, or the vast majority of people, actually believe in a strong, strong way.

But within that there’s different groups. There’s one group that’s totally motivated by primarily making money, right? Then there’s people who have a strong belief in the technology of cryptocurrency. Where the Biden administration was essentially declaring war on cryptocurrency and was unbanking cryptocurrency—just applying regulatory pressure versus having a regulatory regime and following it and so forth. So [those cryptocurrency advocates] were pro-MAGA. There’s a group of people who believe that the Democrats are overly captured by Palestinian interests and would be against the state of Israel. So they’re in the kind of pro-MAGA group. Then there’s also the pure opportunists for power. Like, oh, it’s our turn to eat.

Now, I think there’s a bunch of people in Silicon Valley who disagree with [the administration], but they’re like, “Well, look, if I speak up or do things, then I am challenging my company. I’m gonna get hostile retaliation, I’ll get a regulatory thing that’s discriminatory just attacking me as a political enemy versus the thing I’m doing, and I’m trying to do this thing that’s good for humanity” and so forth.

Of course I get messages from people saying, “You should be quiet. You should keep your head down.” One of the things to think about, when you feel fear, is the opportunity for courage. The fact that you feel fear about speaking what you think is true about who we should be as Silicon Valley or as Americans—that’s precisely the degradation of American society. That’s precisely the opportunity for courage.

What I’m hopeful for in ’26 is for more people speaking up. Speaking truth to power is the point of freedom of speech, is the point of American society. I think that there’s a bunch of different factions in the Valley that have been keeping their head down out of this fear of retaliation under a rationalization of: “Hey, my contribution is to build this new company.”

The way that ICE is operating is terrible for people. Tariffs are terrible for people. Anti-vaccination is terrible for children’s health. Just speak up about the things that you think are true. Do that and do not let fear and intimidation and hostility, the weaponization of the artifacts of state, quiet you.

You talked a minute ago about fear, and I couldn’t agree more. It’s something that we talk about as a newsroom at WIRED all the time, and especially in the last year. Are you fearful? You are a prominent person. You are a very wealthy person. You work in this industry. Do you worry about this? Trump ordered an investigation into you.

Twice!

I’m referring to the Epstein situation.

There was the one before, which was this fictional organization of antifa, which I only know from right-wing media invention.

I am also unfamiliar with the organization of antifa. I can’t say I’m familiar. But we’re talking about the president of the United States here. We’re talking about someone who has clearly demonstrated an appetite for retaliation. Does that scare you?

I’m rational. So fear and concern are part of the reaction. But when you feel fear, you have to evaluate and decide what that means for you. What it means for me is: Look, if I’m not willing to stand up, how can I ask other people to stand up against the fear and intimidation that the administration is trying to practice?

I’m sure there’s a whole bunch of people that are in the red, MAGA ecosystem that go, “Oh yeah, I’ve heard of this Reid Hoffman guy, isn’t he just a criminal?” because Trump called for an investigation. Trump also called for an indictment of [James] Comey, which was legitimately thrown out. It’s precisely the staying silent that allows the bad stuff to happen. It’s like the Germans who stayed silent in Nazi Germany. People say, “Well, yeah, that’s wrong …” and they tell themselves rationalizations.

Could never happen again …

Yeah, and “it doesn’t really mean anything,” and “he’s just being political.” Look, that’s precisely the thing that degrades our society, that degrades our democracy, that degrades our rule of law. Speak up.

We’re speaking during the week of December 15, and the president has, in theory, a deadline of this Friday to release all of the Epstein files. Now, you have called for those files to be released. You’ve been very public about that. Obviously, you were tied up in this. You’ve spoken about it. When you pushed to have all of these files released, all of the intelligence released that the Justice Department has on Epstein, why is it important to you that it all comes out? What do you think it means for the president, assuming more information is released?

I had a small number of interactions [with Epstein], as you know, fundraising for MIT, and have apologized for that. Once I realized what was involved in that, I was like, “Oh shit, this is terrible. I’m really sorry.”

I didn’t even know who Epstein was in the whole, like when he was put in prison and released as a registered sex offender and so forth. It was all political attacking. But I didn’t speak up about that, because what I concluded is that the thing that’s most important is first and foremost justice for the victims, right?

Then, of course, this year it goes to “oh, we’re trying to defend our own misdeeds by trying to portray Epstein as a Democrat, and it’s all these Democrats’ fault,” when [the administration] themselves had campaigned vigorously on releasing all the Epstein files.

So I was like, “Look, you guys have the Epstein files. You’re gonna use this as a slander tactic for politics and further harm the victims. The simplest way to give justice to the victims is to release all the files. Show everyone what the truth is. I think that’s part of the reason why I was driven to speak up about this. Because despite the fact that the first and foremost important thing always is the victims, the question is, if you’re gonna try to politicize this, then simply live in truth.

Sure. The more information that’s out there, the better.

Yeah.

Let me pivot a little bit to talking about the future for a few minutes. You’ve done a lot. You do a lot. What do you still want to do? What is on your bucket list that, at this point in your career, you feel like you have not yet crossed off?

I do think we are alive at one of the most amazing times to be alive. Maybe the most, with AI and all the rest.

This is going to bring some great early January optimism to our listeners here.

That’s part of the reason I cofounded Manas AI with Siddhartha Mukherjee, to tackle cancer, to tackle a whole bunch of different diseases.

I think about the fact that we’ll all have a medical assistant, an educational assistant, a legal assistant, that is essentially available to everybody. It’s a line of sight to making this happen, and we just have to sort out some regulatory and other kinds of issues for this.

I wanna help with that. I want to help with navigating. The first reaction to technology in all human history is fear. To embrace it as pro-agency, both in terms of what we build but also in terms of how we understand it and how we do it. There’s a reason I tell everyone to start using it.

I have this thing. It’s basically humanity, then society, then industry. So part of it is, helping humanity and society I think is a lifetime goal, all the way to when I’m moving around on my walker. Then, obviously, participating in the industry stuff in various ways because I do think industry can be a very good way to do this.

Well, then let me ask you this, which bucket—humanity, society, industry—does AI fall into?

All.

Now, before we wrap up, we’re gonna play a very quick game. The game is called Control, Alt, Delete. It’s how we wrap up every show. I want to know what piece of technology you would love to control, what piece would you love to alter, or change, and what piece you would love to delete, or vanquish from the earth.

Do you want one answer for each? Two answers for each?

One. Let’s be disciplined.

Control social media for kids.

OK.

One of the things that most of the world doesn’t really understand is Silicon Valley is also broadly in line with this. If you have kids engaging with this, it should be in ways that have the kind of protections that we generally have for kids, including parental involvement and so forth. So, I’d control social media for kids.

Great.

Alter, I think it’s like let’s go shape AI, right? We want it to be American intelligence. We want it to be embodying the views that we aspire to as Americans in terms of empowerment and freedom and economic prosperity.

Then, delete. It’s very hard for me to delete a technology versus just shape it, like there’s a lot more to alter. I think that we want to be thinking about our collective media systems and how we learn collectively. So how do we have disinformation being weeded out by the operation of the system in terms of people learning collectively? Vaccine misinformation is the example that I most often give. So, for example, if I could delete disinformation at scale, I would do that. But it has to be through a collective learning process.

Well, I think for the sake of the game you can say you want to delete misinformation.

Yes.

Let’s do it. Let’s Delete it. Reid Hoffman, thank you so much. Such a thoughtful conversation. I really appreciate it.

I look forward to the next.

How to Listen

You can always listen to this week’s podcast through the audio player on this page, but if you want to subscribe for free to get every episode, here’s how:

If you’re on an iPhone or iPad, open the app called Podcasts, or just tap this link. You can also download an app like Overcast or Pocket Casts and search for “uncanny valley.” We’re on Spotify too.

The post Reid Hoffman Wants Silicon Valley to ‘Stand Up’ Against the Trump Administration appeared first on Wired.