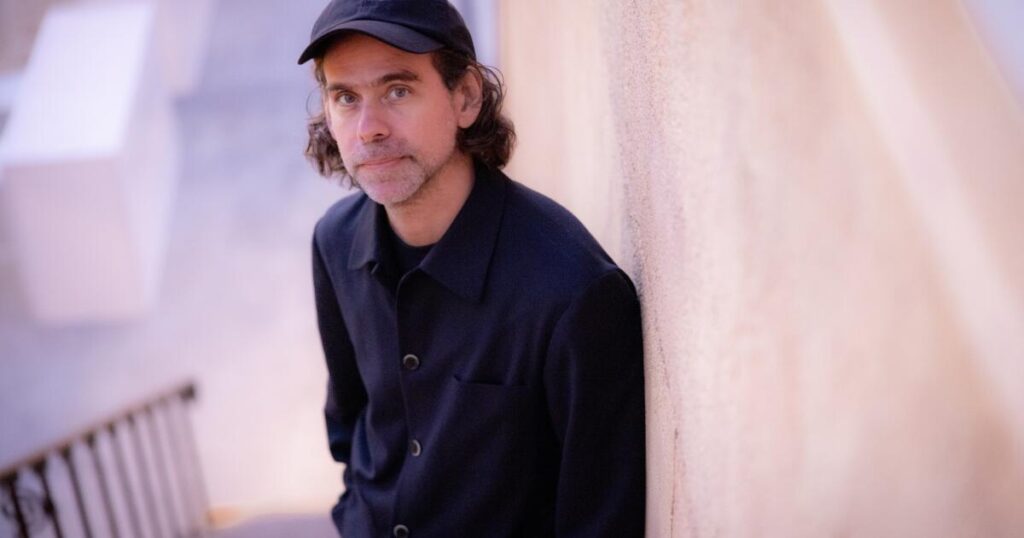

A few days before Sunday’s Golden Globes ceremony, Bryce Dessner admitted with a laugh that he’d come to Los Angeles without a tuxedo — something of a problem, given that he was up for an award.

“The movie people think about what the actors are going to wear, of course, but the composer — who cares?” he said last week over lunch in Beverly Hills. “I was like, ‘Guys, do you have something I could borrow?’”

He might consider getting a tux of his own: Though Dessner and Nick Cave inevitably lost the original song prize at the Globes to the chart-topping “Golden” from “KPop Demon Hunters,” their title theme from director Clint Bentley’s “Train Dreams” made the shortlist for an Academy Award nomination, as did Dessner’s score for the movie about a laborer in northern Idaho in the early 20th century.

Adapted from a 2011 novella by Denis Johnson, “Train Dreams” follows Robert Grainier (played by Joel Edgerton) through 80 years of life in all its turmoil and routine; we watch as he cuts down logs in the forest, as he nurtures a romantic relationship and becomes a father, as he returns home one day to a nightmarish discovery from which he never quite recovers. A stirring meditation on work, love, nature and grief, the film doesn’t contain much dialogue — critics have compared it to the movies of Terrence Malick — which means that Dessner’s gently rippling chamber-folk music is an almost equal partner to the images in the storytelling.

“It’s the water of the river that moves the film along,” Bentley said.

The title song features a haunting vocal performance by Cave, the veteran Australian post-punk singer and songwriter, who was so taken with Dessner’s music that at first he was reluctant to take part.

“The last thing someone who’s crafted a beautiful score wants is some rock star to come in and sing all over the top of it,” said Cave, himself an experienced film composer. “It’s happened to me many times.”

Best known as a member of the Grammy-winning indie-rock band the National, Dessner, 49, is one of a growing number of rock musicians finding a place in Hollywood. Last year’s winner of the original score Oscar was “The Brutalist’s” Daniel Blumberg, who got his start in the band Yuck; other composers on this year’s shortlist include Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood (for “One Battle After Another”), Nine Inch Nails (“Tron: Ares”) and Daniel Lopatin, who makes records under the name Oneohtrix Point Never (“Marty Supreme”).

And Dessner isn’t the only member of the National to establish a successful career outside the group: His twin brother Aaron is an in-demand pop producer who’s collaborated with Taylor Swift, Ed Sheeran and Brandi Carlile, among other acts.

Yet “Train Dreams” feels like a breakthrough for Bryce Dessner — the point where his backgrounds in roots music, concert performance and film scoring converge.

He came on to the movie early, having previously worked with Bentley on 2021’s “Jockey” and 2023’s “Sing Sing” (for which Bentley and his creative partner, Greg Kwedar, earned an Oscar nod for adapted screenplay).

“They sent me the script and I composed a fair amount of music” as Bentley was shooting, Dessner said, “which tends to be a bad idea.” He recalled a similar experience about a decade ago on Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s “The Revenant.” “I wrote like two hours of cello music and then Alejandro — he’s the nicest person — he was like, ‘So, I have to tell you — I don’t think we need cello.’”

Dessner, who lives in Paris with his wife and young son, was dressed in his usual all-black, as indeed he would be the next night during a live-to-screen performance of “Train Dreams” at the Egyptian Theatre.

“But in this case it worked, I think because it’s a different kind of film — more like a cinematic poem,” he said of “Train Dreams.”

Some of Dessner’s cues evoke the chugging rhythms of a locomotive; others, he said, were inspired by the raw splendor of the Pacific Northwest — a landscape he immersed himself in by recording much of the score at Flora Recording in Portland, Ore., where the National had worked before.

“It’s got analog gear and old ribbon microphones and a janky upright piano,” he said of the studio. “I wanted some dust on the sound.”

For the movie’s title song, Bentley said Cave was the only person he could imagine striking the right tone: a delicate blend of weariness and gratitude.

“I actually don’t know if I could’ve moved on if he’d turned us down,” the director said.

In a phone call, Cave, who called himself a huge fan of Johnson’s book, said he watched the movie “with one hand over my eyes just because I thought they might’ve done a terrible job of it.” He laughed. “But within a few minutes, I just eased into it. I was very moved.”

He said the song’s lyrics, which lay out a succession of stark images from Robert Grainier’s world, came to him as he slept after seeing the film. “It was a gift from a fever dream,” he said.

As a parent who’s lost two sons, did Cave identify with Edgerton’s portrayal of a father in mourning?

“Very much so,” he said, adding that he’d first read Johnson’s book years ago, before his teenage son Arthur died in an accidental fall from a cliff near the family’s home in Brighton, England. “Obviously, it was a book about grief, but it didn’t affect me in that way. Then I read it again — no, actually, I listened to Will Patton’s audiobook, which is a work of art in itself — and suddenly it wasn’t something I read from a distance.” (Bentley’s movie employs Patton’s narration in voice-over.)

Asked whether he has a favorite line from Cave’s song, Dessner — who hears “Train Dreams” in a kind of conversation with the singer’s latest album, “Wild God” — picked the song’s chorus, in which Cave sings, “I can’t begin to tell you how that feels.”

“It’s like the whole film, in a way,” the composer said. “It’s about what art can do.”

Dessner and his brother grew up in Cincinnati, where Bryce was playing flute and classical guitar by the time he was 12 or 13.

“He was also really good at math,” Aaron recalled. “The combination of those things always felt related to me.”

For the Dessners, music was “just what you did as suburban kids at a time when there was nothing to do,” Bryce said. “You either do drugs or you play music.”

Bryce joined the National in New York after earning a master’s degree from the Yale School of Music. (The band’s other members are singer Matt Berninger and a second set of brothers in bassist Scott Devendorf and drummer Bryan Devendorf.)

“It was a little bit of an accident that we ended up in a band that got popular,” Aaron said, but that’s definitely what happened. By the mid-2000s, the National’s albums were regularly topping critics’ lists; by 2011, the band was headlining the Hollywood Bowl.

Bryce got seriously into film music after Iñárritu heard a piece he composed for Gustavo Dudamel and the L.A. Phil in 2014; the director called him the next day, Dessner recalled, and asked him to work on “The Revenant.”

These days, the members of the National are “really enjoying a break,” Dessner said, after dropping two albums in 2023 and touring behind them in 2024. He’s confident the band will come back together but figures it’ll be a year or so before he and his bandmates get anything going again.

Until then, he’s focusing on concert music — “I just got asked to write a concerto for the ondes martenot,” he said, referring to the early electronic instrument Greenwood famously used on Radiohead’s experimental “Kid A” album — and occasionally collaborating with his brother on Aaron’s pop productions.

“Bryce is always going to do something interesting in any setting,” said Aaron, who recently asked him to orchestrate a song for Florence + the Machine.

And of course there’s the long road to the Oscars with the quiet but powerful “Train Dreams.”

“I’m kind of excited to be a fly on the wall in a room with Spielberg and Scorsese and all these people,” he said ahead of the Golden Globes.

As awards season kicks into gear, does Dessner harbor any hope of somehow triumphing over the world-conquering “Golden”?

“I have to say yes,” he replied with a laugh. “But no.”

The post How Bryce Dessner got ‘some dust on the sound’ of Netflix’s ‘Train Dreams’ appeared first on Los Angeles Times.