CARAYACA, Venezuela — In the lonely house at the edge of the forest, an old man picked through the detritus of his life. Over here was the bed he and his wife had shared for decades. Over there, the trumpet his son had played in the military marching band. And here was his faded image of Hugo Chávez, giving a military salute in his red beret.

All of it, gone now.

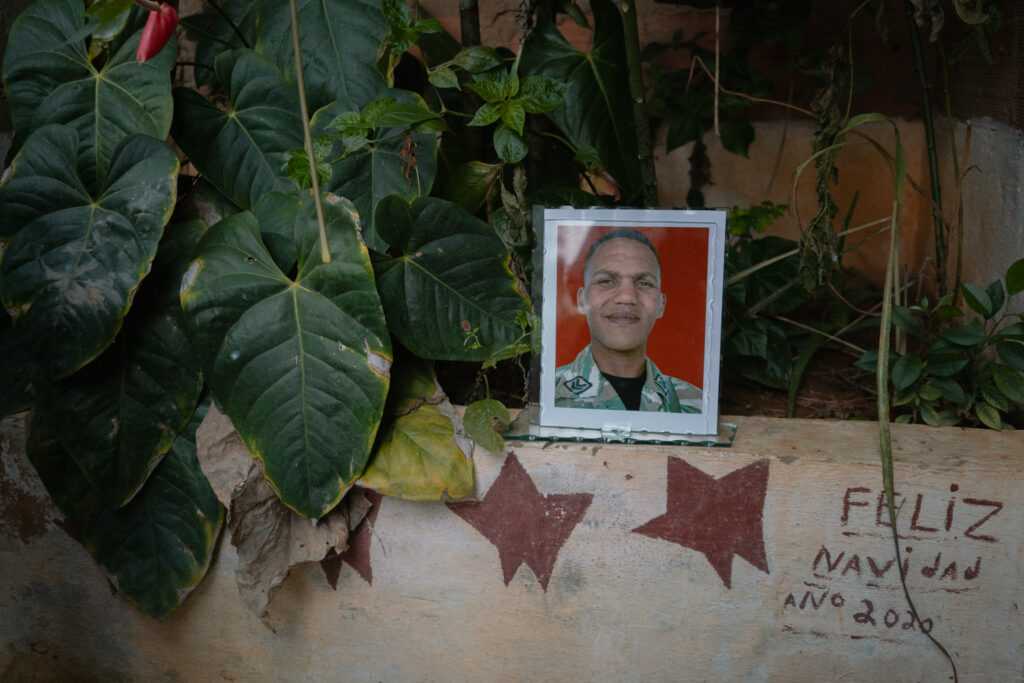

His wife was dead, taken by illness last summer. The socialist movement Chávez once led seemed as faded as the photo Salvador Rodríguez, 74, held in his calloused hands. And now his son, the boy who’d always asked for Rodríguez’s blessings, who’d helped him through the anguish of his wife’s passing, had been taken from him, too — killed in an explosion during the mission by U.S. forces to capture Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

“I have his cédula right here,” he said, pulling out the seared identification card of José Salvador Rodríguez, 32, who’d served as a member of Venezuelan military. “It was burned by the explosion.”

Like many other impoverished households across Venezuela, theirs was a family that had believed in everything Chávez and Chavismo had promised. In a nation where White political elites once controlled most of the nation’s oil wealth and power, Chávez, a career military officer of Afro-Venezuelan heritage, was among the first to recognize people who looked like himself — Black, poor, marginalized.

Following his 1998 election to the presidency, Chávez harnessed an oil boom to fund social programs that educated, fed and housed struggling Venezuelans in Tirima, the wooded enclave on the outskirts of Carayaca where Rodríguez lived with his wife and son, and places like it.

Soon, however, the oil run came to an end, Chávez was dead, killed by cancer in 2013, and the socialist “revolution” he’d left to Maduro had been handicapped by corruption, cronyism, incompetence and U.S.-led sanctions.

But Rodríguez still believed. So had his son, José.

Serving in the Venezuelan army — first in the Bolívar Battalion, then in the formal infantry — had given his son purpose. José had loved music, anything from salsa to reggaeton, and pursued his passion playing the trumpet in the military marching band. Then late last month, he volunteered for a shift, in part because he wanted to collect a coffee machine he’d won in a raffle, but mostly because that’s just who he was.

“A hero to the fatherland,” Rodríguez said.

The morning of Dec. 31, when he left for his shift at a military station in northern Caracas near Chávez’s mausoleum, he looked back at his father and, as always, asked for his blessing. He promised to be home to commemorate the five months since his mother’s passing the following week.

Two days later, Rodríguez was awoken by a loud crash. His first thought was that it was storming outside. He stuck his head out the door and realized he was wrong. After weeks of anticipation and uncertainty, as the American armada amassed along Venezuela’s coastline, it had finally begun: “War in Venezuela,” he recalled saying.

He returned to bed and, praying for “nothing to happen,” fell back asleep.

The next day, he learned that some Venezuelan soldiers had died in the brief melee before Maduro’s capture, but only began to worry that José had been among their number when his son didn’t return any of his calls. Rodríguez called one of José’s military friends.

“Are you José’s father,” the voice on the other end asked.

“Yes,” he said.

There was a pause.

“José is dead.”

Rodríguez clutched his chest and fainted, he said. He was taken to the Carayaca hospital, where the doctors feared the shock of his son’s death would kill him. His blood pressure had soared over 200.

“Listen to me,” Rodríguez recalled the doctor saying. “We need to lower your heart rate, because you could die. You need to calm down.”

Later, Rodríguez found the courage to visit the military station. A commander said José had displayed extraordinary valor the night of his death. After explosions had lit up the Caracas sky, and it was clear the Americans were attacking, other soldiers had refused to leave the protection of the base, claiming aches or pains. But José, the commander told Rodríguez, hadn’t hesitated.

“He said, ‘I’ll go. For my fatherland, I’d give my life,’ ” Rodríguez remembered the commander saying. He went out with another soldier. They were equipped with a large gun capable of downing aircraft. But they hadn’t gotten off a single shot before a giant flare consumed them.

“It burned his entire face,” Rodríguez said.

The funeral was beautiful, he said. The military gave him full honors. The commander had to hold Rodríguez up.

“I cried until there was nothing left,” he said.

Days later now, he was back home at the edge of the forest. The television he’d watched with José was turned off. So was the computer where they’d seen movies. Nothing was going in the kitchen, where Rodríguez had prepared elaborate meals for his wife and son.

The old man looked over at the Christmas tree. It was still erect, two weeks past the holiday. Rodríguez hadn’t wanted to celebrate. It hadn’t felt right in the absence of his wife. But José had said they had to do something. So they’d put up the tree together.

Now Rodríguez didn’t want to take it down. At least not yet.

Helena Caprio in Caracas contributed to this report.

The post In a Venezuelan home, a father grieves ‘hero’ son killed in U.S. raid appeared first on Washington Post.