MANHATTAN, Kan. — Inside a small beige room in a modest beige house, three Afghan refugees gathered around a long table where a lifelong Kansan had prepared for them a lesson about the Constitution.

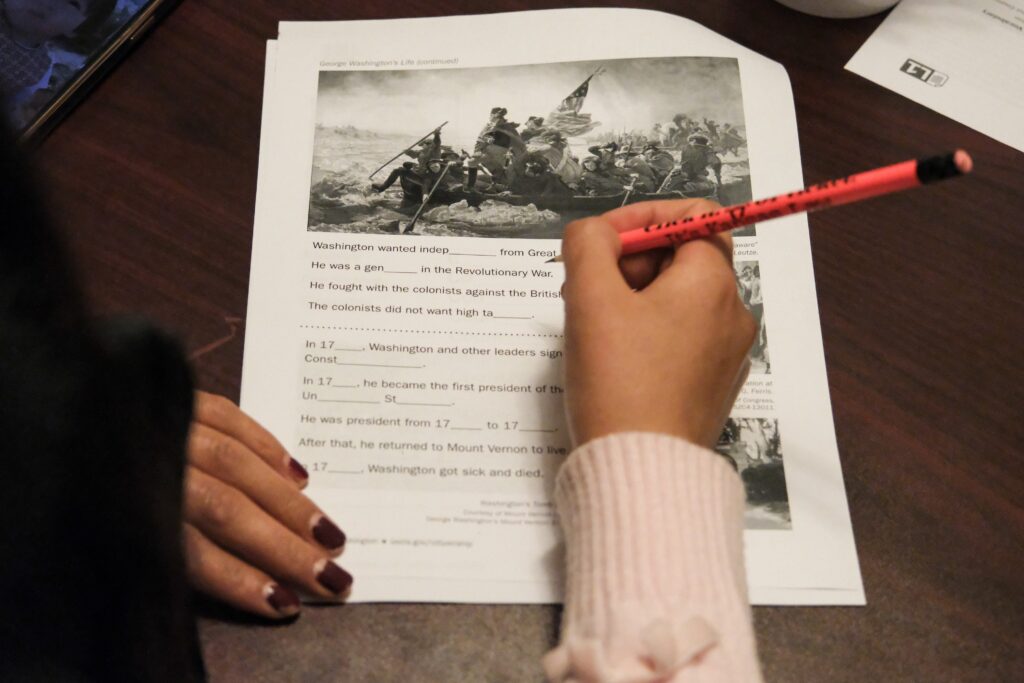

“When the U.S. fought for freedom, they needed to create new rules,” she told them on a Monday evening in early December. “It starts with the phrase ‘We the People.’ Remember that. We the people.”

Rohina Safa, 28, scribbled notes as she learned about the power of citizenship, clinging to a hope that she and the others might one day gain it. Nearly four years ago, she and the two other Afghans at the table fled their homeland to escape persecution from the Taliban. When they set foot in America, lawmakers and veterans groups across the nation eagerly embraced them. The urge to help was so strong that here, in a small city in the center of the country, local veterans started a refugee resettlement agency dedicated to helping them find a new life in Kansas.

But over the past year, the women have had to navigate a different America, one in which the zeal for their presence has begun to fade. Under a new administration and in the wake of a national tragedy, they had little choice but to study American history to deal with the uncertainty of the American present.

Weeks earlier, an Afghan refugee trained by the U.S. military allegedly shot two National Guard members — one fatally — who were patrolling near the White House. Within hours, on the eve of the Thanksgiving holiday that the women had recently learned about, President Donald Trump’s administration was using the shooting to justify, and amplify, his hard-line stance against refugees.

Since Trump’s inauguration, his administration had severely restricted the acceptance of refugees from countries other than South Africa and slowed the issuance of green cards. States suspended access to food stamps and Medicaid for those seeking asylum. And after the shooting, Trump vowed to review the background of every Afghan refugee, saying he hoped his policies would yield “reverse migration” from the United States. “We have enough problems. We don’t want those people,” the president said of Afghans and other refugees.

The harsh language sowed fears among Afghans nationwide that their pursuit of the American promise would soon be met with prejudice, rejection or even deportation.

“Every night, I am thinking about this,” Safa said. “If they send me back there, what am I going to do? They are sending me to my death.”

All three women at the table were Hazara, an ethnic group that has faced persecution for centuries in Afghanistan. They had benefited from the American occupation, which opened opportunities for women to further their education in a country that largely prohibited girls from receiving an education. Safa, 28, studied to become a neurologist. A woman in her 30s at the head of the table had been a trained psychologist.

“And what were you?” the teacher asked a third woman.

“I was in university,” said Fatima Farahmand, 24. “I was studying Russian.”

When the Taliban seized power in 2021, the women were educated and unmarried. That meant they had to run.

The refugees who settled in Kansas tried to choose their words carefully, if they were comfortable speaking publicly at all. Many of them were women whom U.S. forces trained to be part of the Afghan National Army and nervous that speaking out might lead to the Taliban harming their families back home. They also feared the wrath of Trump, a president known for seeking retribution.

Safa had been proud of her three years in Kansas. She had worked factory jobs assembling mailboxes and hoses. She completed training to become a certified nurse’s assistant and began studying to become a licensed practical nurse in an area short on medical workers. She got off public benefits, learned English and adopted American fashion.

After her night shifts, Safa brewed tea and opened a worn copy of Rumi’s poems, searching for a sense of tranquility. Rumi always helped her deal with life’s big questions. She also needed to answer the smaller ones, like the 128 possible questions she could be asked during a U.S. citizenship test, which is why she and the other women came to a class in the tiny house twice a week. There, they were learning the fundamentals of a country whose values were becoming more unpredictable.

“When I got here, I just wanted to live like these [American] people,” Safa said. “I want to go to university and have a good job. Most of all, I wanted freedom. I’m so scared I won’t get it.”

In Manhattan, Aaron Estabrook had been able to obtain his own American Dream. After serving with the U.S. Army for a year in Afghanistan, he moved here and graduated from Kansas State University, hoping to dedicate his life to public service.

He was serving on the school board in 2013 when a message popped up on his Facebook page. It was from Matiullah Shinwari, an Afghan who had repeatedly saved his life.

When Estabrook was abroad, a commander had given him orders to find a trustworthy Afghan to assist them. He searched a local tent city and noticed Shinwari. He seemed kind and had a background teaching English; his speedy speech contrasted with Estabrook’s methodical manner of speaking. The two journeyed on more than 300 missions together, largely going ahead of troops in dangerous places to assess whether enemies would fire at them. “We were the grunts,” Estabrook recalled.

In Shinwari’s Facebook message, he told Estabrook that he had been living in a dangerous part of the country and needed protection. He asked for Estabrook’s help to come to the U.S. Estabrook vowed to get Shinwari out of harm’s way, just as the interpreter had once done for him.

After a friend warned Shinwari how expensive it might be to move to California with five children, he decided it would be best to follow Estabrook to a more affordable place. Shinwari waited for 3½ years as immigration officials vetted him. Meanwhile, Estabrook emailed the State Department and Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kansas) at least once a month to urge them to get Shinwari to the U.S. before he lost his life.

When Shinwari arrived in 2017, Estabrook was his de facto case manager, helping his children receive their vaccinations and get registered for school. Shinwari found jobs as a bus driver, then as an interpreter for the school district and health department.

Four years later, in August 2021, the Taliban recaptured Kabul. Now it was Shinwari on the receiving end of phone calls and messages from interpreters and intelligence officers who needed help.

Testifying before Congress, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the time, Gen. Mark A. Milley, described the U.S. evacuation as a “strategic failure.” The Taliban’s resurgence was swifter than U.S. forces had anticipated, endangering American civilians and Afghan allies alike. And Estabrook, now on the city commission, became one of the scores of veterans who took on a new mission to protect their Afghan associates, calling lawmakers, starting nonprofits, pleading for help in TV segments.

Estabrook said he was watching CNN when he saw another veteran named Fatima Jaghoori pleading for the government to assist unmarried Afghan women before they suffered from the Taliban’s cruel oppression. To his surprise, Jaghoori was also living in eastern Kansas.

The two decided to work together. While Estabrook leveraged his position as a city commissioner to secure housing and employment options for the Afghans, Jaghoori worked with other veterans to come up with an exit plan for a group of Hazara women, along with U.S.-trained female members of the Afghan National Army. In Afghanistan, she helped to arrange safe houses, where the women were instructed to stay inside to avoid being caught.

If someone heard a rumor that the Taliban were on to them, the women would rush to find hijabs and drape them over their heads. They’d turn off their cellphones, switch off the lights and pack themselves into a single, dark room for hours.

Then, at dusk, they’d steal from one safe house to the next, until they were allowed into a refugee camp in Abu Dhabi. There, the women waited for 10 months while the U.S. government vetted them.

Jaghoori and Estabrook discovered a logistical obstacle to getting the women to Manhattan: Refugees had to live within 100 miles of a resettlement agency. Together, Jaghoori and Estabrook founded the Manhattan Afghan Resettlement Team, or MART.

Nearly 200,000 Afghan refugees have come to the U.S. since 2021, with 211 of them resettling in Manhattan. When the refugees began arriving, piles of clothing and toys and teakettles crowded the mayor’s front porch and garage. Someone donated a 2002 Ford Windstar to drive families around. The university lent empty dorms to provide temporary housing.

The community of 55,000 became home to Afghan factory workers, Afghan custodians, Afghan bus drivers.

Shinwari could not contain his excitement to have more Afghans in his community. He wanted them to see the big city, so they traveled to Kansas City and Omaha, and he watched their delight upon seeing gorillas at the zoo. Their children taught their classmates how to play cricket. When a doctor complained that the refugees were so dehydrated that he could not draw blood from them, MART hosted a workshop on the importance of drinking water and distributed reusable bottles.

“It was beautiful,” Shinwari said.

The new resettlement agency used donations to buy the modest beige house, which was the childhood home of writer Damon Runyon, whose tales of New York gamblers and swindlers inspired the classic musical “Guys and Dolls.” Because the team also resettles families from other countries, the A in MART now stands for “Area,” not “Afghan.”

Jaghoori, a Hazara woman who immigrated to Kansas when she was 10, began to believe the U.S. was willing to move beyond the prejudice she had encountered as a child.

“My entire family has sacrificed for this country,” said Jaghoori, whose husband died while serving in Afghanistan. “I always wondered when would we be seen as Americans, not just Afghans who live in America.”

On the first day of the Trump administration, Jaghoori worried these new refugees would see an uglier, harder side to the United States. The administration paused refugee resettlement and wiped out funding for aid programs helping them. The Kansas legislature zeroed out funding for its state refugee office, MART’s primary budget source.

The state office had enough in reserve to keep the agency afloat for another fiscal year, but what will happen after that is unclear. No state money means fewer case managers — if any — to help the Afghans navigate an increasingly complicated path to a green card or citizenship.

On Nov. 1, the state enacted new requirements and refugee families began to lose public benefits. Jaghoori held on to a fleeting hope that these measures would be temporary, until the shooting and the political fallout dispelled that faith.

“These past 12 months have been nothing but fear and trying to stay hopeful,” Jaghoori said. “I am trying to find some sort of goodness within how these guys are living and how much they’re flourishing. But to know that it could possibly be taken away, they were shown a dream that could possibly never come true.”

Each day, Jaghoori said, she wakes up with the hope that her senators, her president or at least a veterans organization will remind the country about the need to help those who could otherwise be killed in a country that U.S. forces occupied for two decades. Each day, Jaghoori said, is disappointing.

“Where is the uproar?” Jaghoori said. “Why aren’t people in the streets?”

Jaghoori said the locals have largely been supportive of their Afghan neighbors. On Giving Tuesday, MART had a goal of receiving $2,000 to help offset the loss of even more public benefits. Strangers donated $2,902.97. Seven new people signed up to volunteer. But some refugees have experienced small differences. The smiles they used to receive have turned into small recoils. A 24-year-old who worked at a grocery store recounted to friends that a man told him, “Your people hate our country.”

“No, no,” he said. “We love your country. We fought with your country.”

Shinwari, who had been living in Manhattan for nearly a decade, was driving an Uber when a college-age passenger asked where he was from. When Shinwari answered, the passenger threatened to call Immigration and Customs Enforcement to deport him. After Shinwari dropped him off, he said, the passenger walked to a police car and started pointing. Shinwari, now a U.S. citizen, was not sure what to make of the interaction. He laughed off the disrespect.

The morning after the class on American citizenship, refugees trickled into the beige house. All of them were trying to make life in the U.S. work, but American bureaucracy was not intuitive.

A man who gave his name as Muhammad, who moved to Kansas in 2023 after working at a university in Kabul, walked inside holding a stack of documents warning him that he was no longer eligible for Medicaid. He went through the process of finding a new insurance plan with a case worker, then said he had another question. He had seen on an Afghan news station that the time limit for work permits was going to be reduced from five years to 18 months.

“Do you know when the 18 months will start? Because I’ve been here about 18 months,” he said. “If I cannot work, I cannot live. I am making progress, but this would set me back.”

No one from the state or the federal government had sent any such guidance for the agency. After a brief internet search, the case worker confirmed that U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services had just made that change. Her jaw dropped. “Good job being on top of that,” she said, trying not to show her frustration. “It’s just, everything is changing real fast. We have to look into it.”

“Thank you,” Muhammad said. “I’m sorry to take up your time.”

His mind began to shift to the alleged shooter.

“When he did that, he hurt all Afghans,” Muhammad said. “I understand Trump; he’s trying to protect his country. But now I feel so much shame. My son is waiting for the green card because he is looking to join the Army. He’s so nervous we won’t get it. He just walks around looking sad. I don’t want him to be sad. I want him to be proud.”

“I know,” the caseworker said. “It’s devastating.”

The following day, Shawn VanDiver, a U.S. Navy veteran who started a nonprofit after helping a friend escape Afghanistan in 2021, stalked the halls of Congress looking for lawmakers who might help. That morning he’d put on a dark blue suit and filled a 24-ounce plastic cup with black coffee, planning to spend his morning racing up and down stairs to find lawmakers willing to defy Trump and publicly support Afghan refugees.

“We are hunting for Republicans,” VanDiver said.

“We are asking for a couple people to be brave,” said Jessica Bradley Rushing, his chief of staff, walking alongside him. “But courage is in short supply.”

He had called, texted and emailed Republican lawmakers who had supported resettlement policies when there was a Democratic president. Now, under a new regime, they didn’t respond to him. He traveled from California to confront them directly.

Some organizations and leaders whom The Washington Post contacted insisted that they had not forgotten Afghans. They claimed to have been working behind the scenes in private meetings, fearing public discussion would be counterproductive. A spokeswoman for Moran, the senator from Kansas, said he wished the Afghan community the best, even though he supported “additional vetting of every Afghan refugee who entered the U.S. after the withdrawal of 2021 and making certain those who have been properly vetted and are in the U.S. legally are authorized to work so they can be productive members of society.”

VanDiver, the president of #AfghanEvac, did not think such efforts were enough.

Walking past an elevator bank, he ran into Rep. Blake D. Moore, a Utah Republican who had sponsored legislation to investigate President Joe Biden’s chaotic evacuation of troops.

“Thank you so much for everything you’ve done for Afghans,” VanDiver said. “We really need you to speak out on this. If it can happen in the next week or two, that would be great.”

VanDiver handed him a small coin that read “Maintain Urgency. Remove Uncertainty.” Moore looked down.

“It’s a challenge,” he said, fiddling with the coin.

Moore’s mouth opened, but words did not come out. Then he uttered: “I mean, you get it.”

VanDiver tried to explain how the public needed to be able to place the alleged shooter, Rahmanullah Lakanwal, in the proper context. (Lakanwal, who federal authorities say carried out the shooting after driving to D.C. from Washington state, has pleaded not guilty.)

“This is one dude who went off the deep end,” VanDiver said. “We can’t have anyone who said they care about allies abandon them.”

“Right,” Moore responded. Without committing to speaking out, the congressman walked into the elevator.

Minutes later, VanDiver saw Rep. Morgan Luttrell, a former Navy SEAL, pacing to his office. VanDiver ran after the Texas Republican.

“It’s a real hard thing to do right now,” Luttrell said before trailing off.

“It’s not that hard,” VanDiver said.

He had more success with Rep. Michael McCaul, who had once chaired the House Foreign Affairs and Homeland Security committees. McCaul, also a Texas Republican, was not seeking reelection and had less reason to fear upsetting the administration.

McCaul told VanDiver that “this case was a major setback” and that he did not want to come off as insensitive to the family and friends of the Guard members who were shot.

VanDiver stressed that U.S. forces trained Lakanwal to kill and told McCaul he suspected the alleged shooter struggled with his mental health. He noted that the Trump administration cut funding for mental health programs for refugees, which would have made it harder for him to find help.

“So, what do you think? He snapped?” McCaul asked.

VanDiver nodded.

“Well, we’ve had a few veterans snap,” McCaul added. “Timothy McVeigh was a veteran. And Lee Harvey Oswald.”

“Exactly!” VanDiver said. “That’s my point. We don’t hold it against all veterans.”

The discussion was enough to persuade McCaul to record a video. They found an American flag at a wall nearby and stood in front of it.

“When it comes to our Afghan partners and allies, they served with our military, they served with our intelligence community,” McCaul said as Bradley Rushing recorded. “The credo in the military is no man left behind, and we promised them that we would protect them.”

“Thank you so much!” VanDiver told him after they finished recording. He walked away and pumped his fist. “Yes!”

He vowed to continue coming back to Capitol Hill until the administration began issuing visas again for Afghans who had helped the military. Since McCaul, only one other Republican — Rep. Joe Wilson of South Carolina — has recorded a video supporting them.

On another day in Manhattan, Salehmohammad Mamon, 42, and his son circled around a silver truck in the city’s bar and restaurant district, his thick black hair flopping in the wind. He was three months into his business venture, a food truck specializing in Afghan dishes. On this day, he parked the vehicle outside of a parking lot near a Popeyes, hoping to court curious customers. The deep lines on his forehead furrowed. The generator was on the fritz, which disappointed a redheaded young man in scrubs who was eager to taste a new cuisine.

“I think I can be successful with this,” said Mamon, his words loud and fast. “I don’t want to rely on government, so I’m trying my own business. I need the money. I have eight kids.”

Mamon had been working in dentistry in his war-torn country. He said everyone in his area had many children during the war because it was not uncommon for children to get caught in bomb blasts and die.

He began to serve as a medic for the U.S. military, applying tourniquets, trying to reattach blown-off body parts. Occasionally, Mamon said, he would see Lakanwal, the alleged shooter. He remembered him as a diligent, risk-taking young man.

“I remember him in Unit 3,” said Mamon, who moved to Manhattan in early 2022. “He was always being sent out with those guys, doing dangerous things.”

From the moment he heard about the shooting, Mamon suspected what might have led someone to that point. Those who worked with the U.S. forces cope with the same violence, the same pressure that can lead to mental health struggles common to veterans. Then, they come to the U.S. and face the hardship of being poor in a new country, a place that could seem like Mamon’s silver truck: a vessel of opportunity that does not always work as it should.

“This is depression,” Mamon said of the suspect’s alleged actions. “It’s a hard thing. To come here and to try. I’ve been happy here because people are kind. I have roots. But there is a lot of depression. Even me, now I’m kind of depressed thinking about what might happen to me if I go back.”

The country had big questions, but in Manhattan, Mamon found something more tangible, more tactile, more kind than the seething he saw on TikTok and on the news. The mayor knows him by name. Mamon didn’t think his English was good enough to pass the board exams to practice dentistry, but he found an Indian restaurant that hired him as a cook. The managers taught him what he needed to do to sell food.

Mamon told a friend he made playing pool that he was saving money to buy a food truck. He did not go to a bank because it was against his religion to take out an interest-bearing loan. The friend invited him over the next day, then offered him $20,000 to purchase the vehicle.

Mamon said he offered to pay $1,000 each month until the money was paid back. No, no, his American friend said. Only do so if the truck is successful.

“There are good people all over this country,” Mamon said. “I would like to have my green card. I would like to be a citizen. But if Trump tells me to go, I have to go. It is not my country.”

The country was not his country, but the city had become his home. Mamon thought about his children, his youngest just 3, born here in Kansas on the Fourth of July. He thought about his eldest, Yasir, who had just finished high school but was taking a year off to perfect his English and help with the truck. Yasir, 19, hoped to study mechanical engineering. And play cricket. And join the military.

“Army,” Mamon said.

“Navy,” Yasir replied.

“If they tell me I have to go home, I would go home,” Mamon said, “but I would want my kids to stay. This place is good for them.”

The post After fleeing the Taliban, they felt safe in America. A shooting in D.C. changed everything. appeared first on Washington Post.