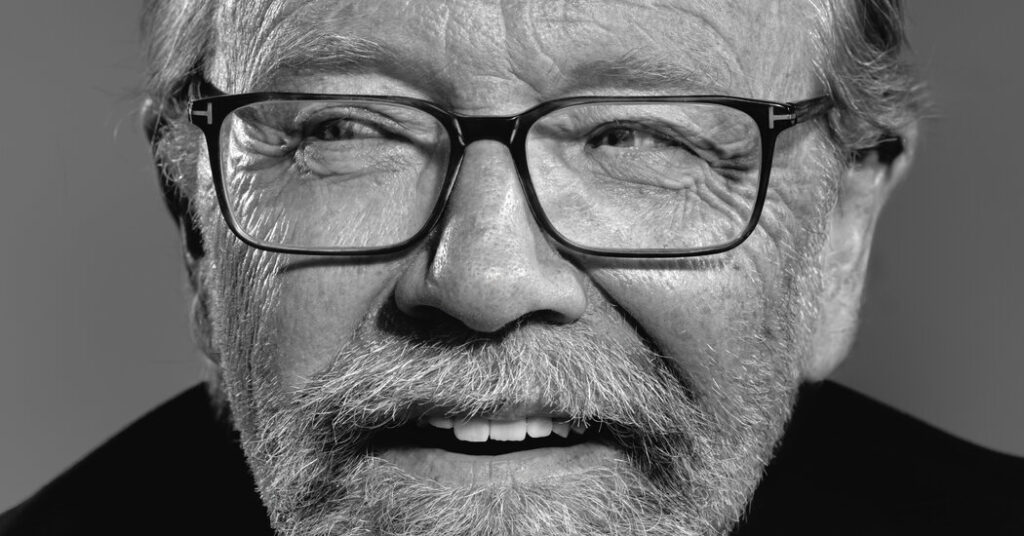

Last fall, George Saunders was awarded the National Book Foundation’s medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. In the speech introducing him, alongside a glowing rundown of his literary résumé — author of 13 books, a past National Book Award finalist — he was called “the ultimate teacher of kindness and of craft.” Pretty good, right? Well, mostly.

The craft part isn’t the issue. Saunders, who is 67 and has a new novel out this month called “Vigil,” about two angelic beings visiting the deathbed of an oil tycoon and climate-change-denial mastermind, has been a revered teacher in Syracuse’s prestigious creative-writing M.F.A. program since 1996. He has also taught fiction to countless laypeople: His 2021 nonfiction work, “A Swim in a Pond in the Rain,” was a book-length distillation of his teaching that, probably to the surprise and delight of his publisher, became a best seller. And out of it came a Substack called Story Club With George Saunders, in which he continues to teach short stories and also shares writing prompts and exercises to more than 300,000 followers.

But then there’s the kindness stuff. In 2013, Saunders gave a convocation speech to Syracuse graduates in which he extolled the life-altering virtue of practicing kindness. That speech went viral and was then repackaged as a book titled “Congratulations, by the Way,” which also became a best seller. The success of that speech wound up thrusting Saunders, who won the 2017 Booker Prize for his novel “Lincoln in the Bardo,” into a public role as something close to a guru of goodness. Which is frankly a little strange, given the razor-sharp satirical bite and morally complex themes of his fiction, and also just an odd thing for someone to have to live with. As he explained in our conversation, he’s as flawed a human being as anyone else, one who’s still wrestling with questions about how best to move through life with a modicum of grace and compassion.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Amazon | iHeart

Your new book, “Vigil,” raised a lot of questions for me, including questions about determinism and how much anyone is responsible for their own life or the decisions that they make. What’s your answer to that? There’s this Chekhov quote that I’m kind of living by lately. He says a work of art doesn’t have to solve a problem — it just has to formulate it correctly. So in this book there are two characters who embody that question, and I think they’re both right. My job, rather than answering your question, is to allow each of them to make the best possible case for their view. So with this book and with “Lincoln in the Bardo,” I wrote myself into a place where the question got more and more profound, and I found myself less and less capable of giving a definitive answer. That’s not for an artist to do. You ratchet the question up, and you go, Yeah, that’s a tough one.

For people who will not yet have read the book, can you explain the characters who represent the two sides of that question? There’s a climate-change-denial architect who’s in the last night of his life. His name is K.J. Boone. A couple of ghosts come to see him, and one of them is this woman, Jill. She died at 22 in 1976, and her idea about things, because of an experience she had at death, is that nobody is to blame, nobody should take credit, we’re just vessels that live out karma, and therefore the only thing to do is to be kind and comfort one another. That’s her view. There’s a Frenchman who died in the 1800s whose view is not that. He’s a vengeful presence. So those two throughout the book are going back and forth over how to approach this sinner in the bed. Those are the two viewpoints I kept trying to refine.

I was hungry for K.J. Boone to get some sort of judgment rendered on him. How do you think about the subject of judgment for the real-world K.J. Boones? Like you, sometimes I’d like for a hammer to drop on them at the end of their life. But for the most part, just looking at my own heart, when I’ve been in sync with truth, I felt better. When I was not in sync with truth, I felt poorly. That might be the only judgment that takes place in this sphere. In the book, in that last 15 or 20 pages, I got a lot of surprises. Things that I was rooting for didn’t happen. That’s the beauty of the writing process. It’s almost like something arises out of me that’s a little smarter, a little more fair, a little more curious, and hovers over the desk for a while. Then the theory is the book urges that spirit out of the reader as well, and the two things merge. So you get this brief period of rarefied communication that seems to inspire a suite of really nice things, like a little more empathy, a little more engagement, a little more patience.

What you just described, how engagement with literature results in these positive side effects — it’s a recurring theme in interviews with you and things you’ve written. I have questions about that. So do I. [Laughs.]

We could point to countless examples of genius writers, people who are as deeply engaged with literature as someone could possibly be, who are giant jerks. So what makes you believe that the hopes you have for what literature can achieve are true and not just a nice thing to hope for? Well, to the first point, it’s a mistake when we think someone who has done something beautiful in art must be a wonderful person. The second thing is that these benefits — I see them happening to me. They are incremental changes of consciousness on the part of the writer and the reader. I’m not claiming it as some kind of universal solution to anything. But to me, it’s becoming clear that writing and reading is a way of simply underscoring that human connection is important, that you can know my mind and I can know yours, which is a vastly consoling idea, and we need it.

I’ve seen you mention in passing that when you were a younger man you were an Ayn Rand Republican. Do you remember how you came to those beliefs and then how you wound up rejecting them? I came to it out of a vast insecurity. I had a couple of high school teachers who intervened on my behalf and got me into the Colorado School of Mines for geophysics. I went out there and was just barely hanging in, and that was really jarring. Along comes “Atlas Shrugged,” and at least the way I read it was: You’re special, because you believe in selfishness. I got caught up on “You’re special.” I could feel that for all of my external defects, inside I was a glowing knight of objectivity. The other thing was just the novelness of “Atlas Shrugged,” the way it called up a world in my mind. That was actually what I loved, that she was a novelist. But then I graduated from the School of Mines, went overseas and was working in the oil fields, and was walking home, possibly a little drunk, one night in Singapore. There was a big foundation of a hotel that was going up, and there was some movement at the bottom. I staggered up to the fence, and there were hundreds of elderly Singaporean women clearing the site by hand. They were literally carrying boulders. Something in that moment just snapped, and I made the connection between those women and my extended family, many of whom were struggling with the big boot of capitalism. And I thought, Oh, I’m on their side. For the first time, I thought, contra Ayn Rand, that these people are the result of a system. This thing that’s happening to them, the way they’re behaving, the difficulties they’re having, isn’t entirely just them. That in turn connected with my childhood Catholicism.

How so? I always loved the woman at the well, when Jesus, as I understood it as a kid, comes up to this woman who’s scorned by all the people and goes, I see you, I love you, I forgive you. I thought that was such a novelistic move. That seems to me part of the magic of fiction, because in fiction I can make a person that I really don’t like — like this guy in the book, he’s a stinker — but through the weird side door of trying to make the language about him more interesting, pretty soon “like” and “dislike” become almost useless phrases. You are him. You have been him. Specificity negates judgment. So as I work harder and harder to know that guy, my sense of wanting to judge him seems juvenile. Anybody can judge. Let’s go deeper. I really cherish that feeling. Of course it doesn’t last beyond the page, and I’m sure if I met his real-life corollary, I’d be sneering at him. But what a blessing to, for a few minutes a day, ascend up out of your habit.

Recently you won a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Foundation, and in one of the introductory speeches, you were referred to as “the ultimate teacher of kindness and of craft.” You’re often positioned in terms of kindness and goodness, almost as a kind of secular saint. And — you just rolled your eyes. I was just keeping myself from levitating.

I wonder if we can complicate that positioning a little bit. The whole kindness thing came out of a talk I did at Syracuse, and the point was not that it’s easy but that it’s impossible. I was never making the case that I had got it, because I don’t. I’m anxious, and I’m sometimes pretty grumpy and I’m also way too busy. That secular-saint business — I’m resisting that narrative, because it jars with what I know about myself as an actual person.

When do you struggle with kindness? Every day. We have an elderly dog at home who’s very sick, so that’s just an ongoing thing of trying to figure out what she needs, and meanwhile I’ve got a call in 10 minutes. So it’s pervasive. I’m aware of this riff about kindness, but it came from one speech that I gave.

Which was then republished in The Times and went viral, and then it was made into a book that also did well. And then after that, you go on a tour and you get to dig into that bit and go, OK, so what does it actually mean? It’s not niceness. That talk was an interesting way for me to realize that maybe I had equated kindness and niceness in too easy of a way. Disconnect those, and it gets to be a real lifelong challenge. Now what I think is that kindness has so much to do with your ability to be in a moment without a whole lot of monkey mind going on. Because then you’re more likely to be able to posit what could be helpful in that situation.

People who are interested in ideas of kindness are a self-selecting group of people. But for this other group of people who maybe aren’t thinking about or don’t care about questions of kindness, is there anything you would suggest that they read to open up the door a little bit? Well, I want to push back on your framing, because even the worst turd on the planet, if you fall down in front of him, he’s going to help you up. So then we get to a different statement of your question: A person who in his own life does value kindness and does love his parents, love his kids, why does he hit the switch on whatever harmful thing he’s doing? That’s a deep question. You can look at our politics right now, and I don’t really have an answer.

What are the links between Buddhism, which you practice, kindness and your art? It’s just the awareness that we have thoughts and they self-generate and dominate us. We mistake those thoughts for us. In both Buddhist practice and writing, you have a chance to go: Oh, those are just brain farts. They’re just happening spontaneously, and I didn’t actually create them, and I’m not sure I really want to take ownership of them. At the same time, they’re affecting my body. So you have to just get clear for long enough to recognize them as being separate from who you actually are.

I meditate, and I think the most beneficial aspect of it for me by far is just what you described: the awareness that the thoughts are coming in but you don’t have to act on them. Exactly. One of the reasons I’m a big advocate of meditation is because I’ve really slacked off in the last two or three years, and it’s interesting to see the old neurosis come back.

How? I notice a lot of feelings and thought patterns from adolescence coming back, like the forest encroaching. Mostly when we say we understand meditation, it’s because we push the trees back a little bit and, ah! Clarity. When I was writing “Lincoln in the Bardo,” we were doing a lot of meditation, and I could feel that there was a certain kind of thinking that I really had associated with my personality, which had to do with snark or sarcasm. Under meditation, that receded enough that I could go, Oh, that’s a habit. I had to increase my tolerance for earnestness in that book and for letting people just tell their stories without trying to fancy it up with my wit. That wouldn’t have been possible except for that the forest got pushed back a little bit.

You mentioned “Lincoln in the Bardo,” which is about figures in the afterlife. In “Vigil,” the new novel, there are more figures from the afterlife. Are you trying to work through something about death? I’m just so happy it’s not going to happen to me. [Laughs.] I mean, your first memory, you’re sure that you’re in a movie and you’re the star of it. Your mom and dad are co-stars, and there’s a cast of millions out there, but you’re the main thing. Also, there’s that second idea that you’re not leaving. That schmuck died, but you’re not going to. Then also that feeling that you’re separate. That you are David, and everyone else is not. All of those are Darwinian, they make sense, but they’re all untrue. Death is the moment when somebody comes and says: You know those three things that you’ve always thought of? They’re not true. You’re not permanent, you’re not the most important thing and you’re not separate. So I think about it a lot, but I find it a joyful thing, because it’s just a reality check.

Relatedly, you often write about salvation, including in the circumstance of someone near death and how they might be saved. But what is salvation to you? I don’t know about the afterlife. But I think any moment in this life when you get clear of that trio of delusions, you’re saved. Because then what’s to be afraid of? The reason I don’t want to die is because I’m me. I’m so fond of me, and even when I’m not fond of me, I’m quite attached to me. I’ve had a couple of times in my life, just briefly, where I could feel, Oh, OK, there’s a little distance there between me and self. If you could get a lot of distance, then death would be no problem.

There was one question I asked you earlier where I thought your answer was a bit of a dodge. Probably.

I had asked about this idea that engaging with literature can make readers and writers more expansive or more generous, despite the counterexamples. And you answered by saying the art, when it’s working, should be better than the person who made it. The question was not really about whether the art is better than the artist; it’s about what effect literature and reading can have on us. But maybe the deeper question is why that idea matters to you? Sometimes I think it sounds like I’m saying literature can cure us. It can’t. It never has. So I think for me it’s always saner to go down to the incremental level and say, On a given day, if a given person reads a given Chekhov story, something will happen. For that 40 seconds after you’ve been nailed by a story, you’re a little different. What I probably believe in is the idea of the sacramental value, which is if you get your bell rung once, and in that moment of having your bell rung, you are more expansive, then the next time you’re not that, you might just go, Oh, yeah, I’m not fixed as this lower version of myself.

But even the idea of literature having sacramental value, that edges toward a justification. I’m always wary of any justification for art beyond its own sake. You’re exactly right. As soon as you say that this justifies art, you’ve made it have to earn its dinner, and some autocrat is going to come in and say, “Oh, I don’t think your art is doing what we want it to do.” So I agree with you. In the end, art answers to nobody. However, I think there are ways in which we’ve sort of pooh-poohed the power of literature and made it kind of a niche, quaint thing, even in our educational structure. Imagine a world where fourth and fifth graders read a Chekhov story a week. Then, through that doorway, you teach them to unpack a text. You teach them to have confidence in their own reading ability, their own perception of the world. I think that would actually be an amazingly powerful thing as a culture. Our daughters went to a really good school, and at one point this fifth- or sixth-grade teacher was teaching Ambrose Bierce, some of those really dark Civil War nonfiction pieces — beautifully written, very ornate and tough, and the subject material was dark as hell. Some parents objected to it. It was too hard. And they got rid of it. Nobody was saying that calculus was too difficult, that calculus was causing their kids trouble. So I tend to be a little bit of a stickler on that. I think we could do better.

Underneath a lot of what we’ve talked about — and your new book — is the idea of karma. Do you believe in karma? Yeah. When I started to read about it in the Buddhist tradition, that word just means cause and effect. Now, we can’t always discern it. But karma for me is just the super-long-range cause and effect.

Do you have any sense of how you’re doing karmically? No. When people use it in a kind of groovy way, they say: “Oh, man, that guy got the promotion over me. Karma’s gonna bite him in the ass.” That’s B.S. That is just “Karma means whatever I want to happen will happen, because God likes me.” Are you a karma person?

I don’t think there is any karma on an individual level. I’m skeptical that people who have done evil in the world are reaping what they’re sowing or even aware of the ways in which they might be reaping what they’re sowing. I’m just spitballing, but I wonder if the punishment isn’t dependent on one being aware. For example, let’s say that I went around with headphones in my ears — really jammed in there — and I couldn’t hear anything. Then I get out on the street and there’s a string quartet. I don’t hear it because of my obsession with these headphones. Am I punished? Not really. But there’s a difference in that experience versus the one with the headphones out. That’s not very satisfying. You think, Oh, Hitler missed out on a lot of opportunities. [Laughs.]

The last thing I want to ask you: I reread “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” your first collection, and in the newer edition, there’s an author’s note in which you write about your life at the time when you were working on those stories. Even though you were in your 30s and struggling economically, you were aware at the time that it was a magical moment in your life — you had a young family, and you were trying to make your way. I wonder if you have any similar awareness about where you are now at 67? I hope so. A couple of months ago I went back to my alma mater in Colorado. They gave me a little temporary office, and as I went upstairs I thought, Oh, my God, I used to live here. The room next to the room they gave me was my bedroom from a fraught year in my college experience. It was the weirdest thing, because that guy that I was was so ambitious and stupid, so not in touch with how one went about having a writing life. But he was pretty earnest. There was something very wild about being almost 70 and standing there and going, OK, so what that kid wanted to do, you kind of did it. I can’t quite describe it. Also, I started late. The first book didn’t come out till I was 38, so I feel like I’m racing to do really good work in whatever time is left. But in that early time, one of the things that was so beautiful was that my stupid dreams of being a prodigy were obviously not going to happen. So for the first time it was like, All right, what if you don’t have any writing career? What if you’re just, hopefully, a good father and husband? And in that space I found that there was plenty to live for. I’d always secretly thought I was kind of shallow, that I was all ambition. And to find out that shorn of that, I still liked being alive and still felt a lot of happiness? That was very sweet.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations. Listen to and follow “The Interview” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, iHeartRadio, or Amazon Music

Director of photography (video): Zackary Canepari

David Marchese is a writer and co-host of The Interview, a regular series featuring influential people across culture, politics, business, sports and beyond.

The post George Saunders Is No Saint (Despite What You May Have Heard) appeared first on New York Times.