Coral reefs are one of those features of Earth most of us take for granted. They’ve always been there, so they’ll keep being there. Vacation backdrops. Nature documentaries. Something “out there” that exists far away from daily life.

They’re not permanent, though. And scientists are increasingly concerned that 2026 could be the year a lot of them stop functioning as reefs at all.

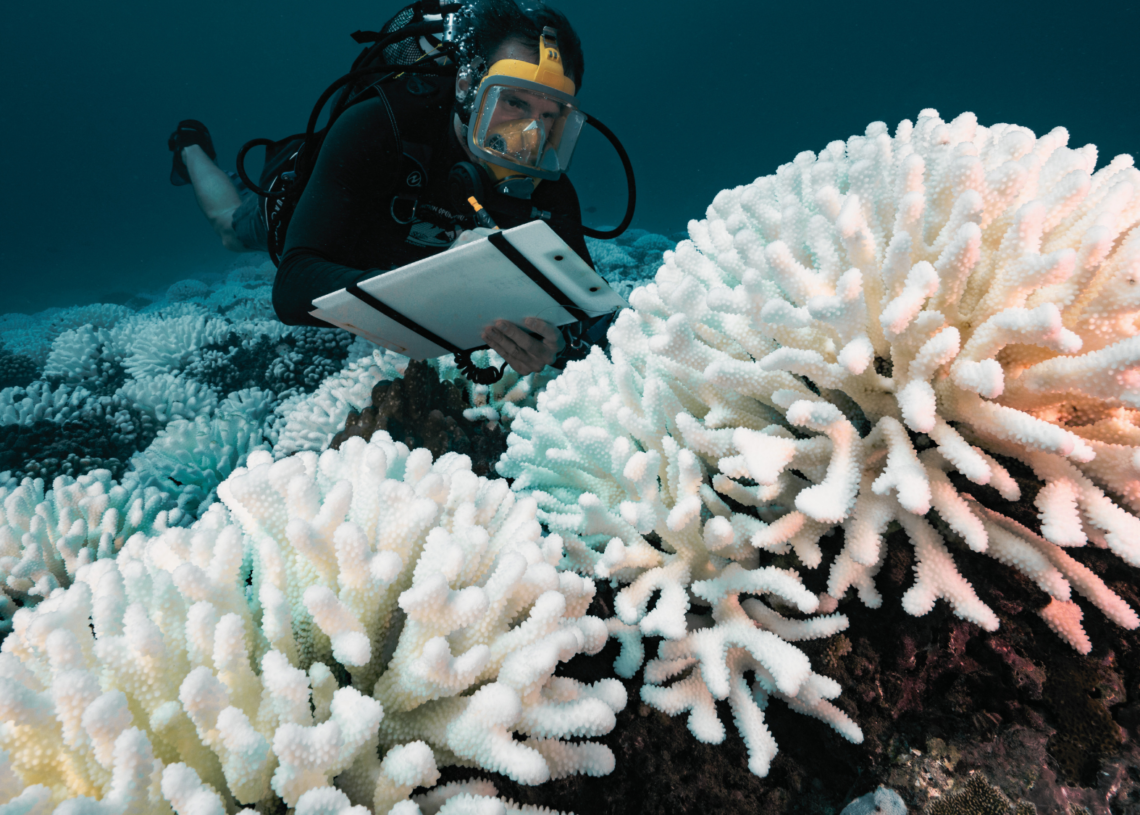

Coral reefs cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, yet they support about 25 percent of all marine species. They’re also extremely sensitive to heat. When ocean temperatures rise too high, corals bleach. That means they expel the algae that keep them alive and colorful. Bleaching doesn’t kill coral right away, but repeated heat stress without recovery time often does. Over the last few decades, researchers estimate that 30 to 50 percent of the world’s coral reefs have already been lost.

What’s making scientists nervous right now is timing. The planet just went through record-breaking ocean heatwaves in 2023 and 2024, pushing reefs in at least 83 countries into bleaching-level heat stress. Normally, reefs get a few cooler years to recover between events. That recovery window is shrinking.

A lot of this comes down to El Niño. As the planet warms, El Niño events are getting stronger and showing up more often, while the cooler La Niña periods are shorter and less effective. Another El Niño is expected in 2026, not long after the last one. Many reefs simply won’t have had enough time to heal. That’s where the idea of a tipping point comes in. Not a single global collapse overnight, but widespread, permanent losses in places that can’t bounce back fast enough.

When a reef crosses that line, the change is stark. Coral dies. Algae takes over. Fish populations drop. New coral struggles to grow. The ecosystem changes into something simpler and far less useful, especially for coastal communities that rely on reefs for food, protection from storms, and tourism.

There are small pockets of hope. Some coral communities in places like the Gulf of Aqaba and parts of Madagascar handled recent heat better than expected. Deeper reefs, known as mesophotic reefs, may act as temporary refuges because they’re shielded by cooler water. These areas matter, but they’re not enough to save reefs on their own.

Heat also isn’t the only pressure. Pollution, overfishing, and coastal development make reefs far more vulnerable. Where those stressors are reduced, recovery is sometimes possible. Parts of the Mesoamerican Reef showed improvement after better fisheries management allowed fish populations to rebound, even after significant bleaching.

Still, the larger picture is uncomfortable. Without serious cuts to carbon emissions, fewer local stressors, and active restoration efforts, coral reefs will keep losing ground. 2026 might not be the moment reefs disappear everywhere. It might be the moment it becomes clear how much we can’t reverse.

The post Could 2026 Be the Year Coral Reefs Collapse? appeared first on VICE.