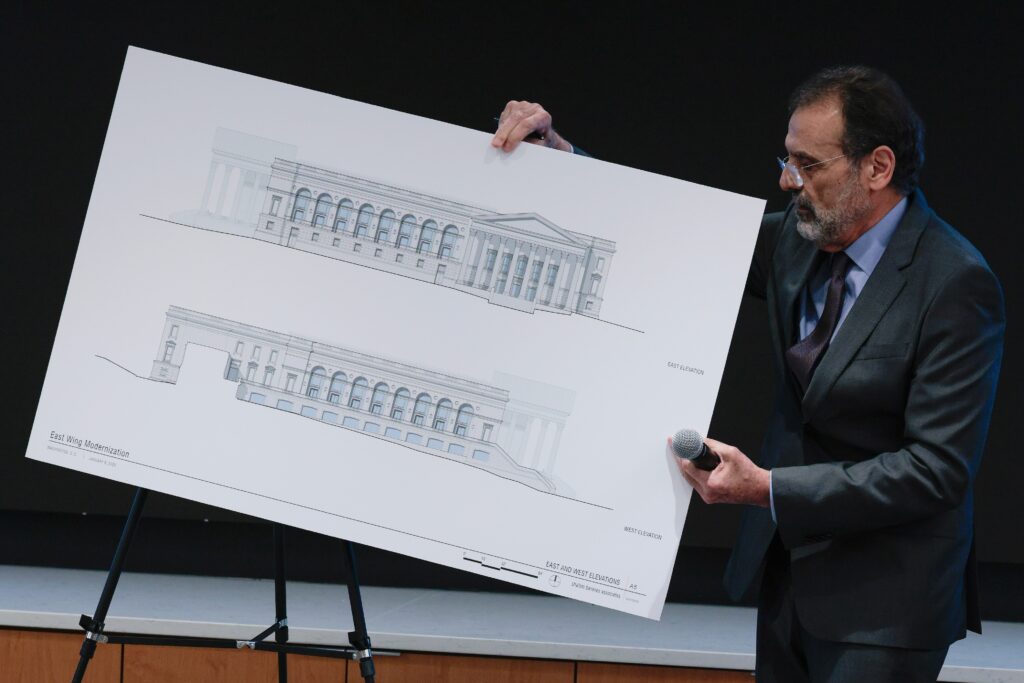

President Donald Trump plans to build his controversial ballroom as tall as the White House’s main mansion itself, the project’s chief architect told a federal review committee Thursday — a significant change of plans that breaks with long-standing architectural norms requiring additions to be shorter than the main building.

Architect Shalom Baranes told the National Capital Planning Commission that the president’s plans call for the building to be about 51 feet high on its north side and taller on the south, where the ground slopes downward. The main mansion reaches 70 feet on the south side, according to the White House Historical Association.

“The heights will match exactly,” Baranes told the panel.

Baranes also estimated the project’s footprint would be about 45,000 square feet, roughly half the size that the administration has described since announcing the project in July. Of that, the ballroom itself would account for about 22,000 square feet and accommodate roughly 1,000 seated dinner guests, he said. Baranes said the 90,000-square-foot size repeatedly cited by White House officials includes a second floor — a clarification introduced as federal oversight bodies begin an accelerated review of a project for which core specifications continue to evolve.

D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson, who has a seat on the panel, pressed Baranes on whether the ballroom’s height could be lowered, saying he was “concerned” the planned addition could overwhelm the White House mansion.

Baranes said it was “possible, not impossible,” to lower the ballroom’s height.

The presentation comes as the White House begins an unusually compressed push to win approvals from two committees charged by Congress with reviewing federal construction. White House officials have said they intend to complete the process in just over two months, a timeline far shorter than comparable projects, former commissioners have said, placing added pressure on oversight bodies that the administration moved to stock with Trump allies.

Baranes told the panel that the White House had abandoned plans to make the ballroom larger. But he said officials are now considering a one-story addition to the West Wing’s colonnade to create symmetry with the planned two-story colonnade that would lead from the White House to the ballroom building. Other features presented Thursday include an office suite for the first lady, a commercial kitchen and a rebuilt White House movie theater.

Mendelson was not convinced a bolstered West Wing colonnade would make up for the size difference between the proposed building and the West Wing.

“It’s just so imbalanced,” he said.

Commission Vice Chair Stuart Levenbach praised the plans, saying such an addition to the White House was needed. As evidence, he told a story about his recent attendance at a White House Hanukkah party that he said felt crowded even though there weren’t that many guests.

“This is going to just open up access to people at a much higher level,” Levenbach said, “and I think that it’s going to be enjoyed for generations to come.”

Half of the commission’s 12 members expressed support for the project; the other half of the panel was noncommittal. The planning commission is scheduled to vote on the project March 5. Administration officials have said they could start aboveground construction as soon as April.

At Thursday’s meeting, the White House publicly detailed for the first time its full rationale for demolishing the East Wing in the fall. Josh Fisher, the White House director of management and administration, told commissioners the Trump administration made the decision after “careful study” found the annex to be structurally unstable, contaminated with mold, topped with aging roofs and equipped with obsolete electrical infrastructure. Engineers also concluded the building’s underpinnings were insufficient to support what Fisher described as “necessary upgrades.”

The explanation followed months of demolition and site work carried out without planning commission review.

It was only last week that the White House laid out a timeline for approvals, laying out a step-by-step path through the two review bodies. Baranes and administration officials intend to give a similar informational presentation to the Commission of Fine Arts at its Jan. 15 meeting, ahead of a vote on Feb. 19.

The president will have to appoint at least four members to the fine arts commission for the body to reach a quorum at its meeting next week. Trump in October fired the panel’s six holdover members appointed by President Joe Biden, and White House officials are currently seeking potential appointees aligned with Trump’s architectural desires.

The Trump administration first met with staff members from the two commissions last month only after a Dec. 17 court order from U.S. District Judge Richard J. Leon, holding separate meetings on Dec. 19 and formally submitting applications for the ballroom project’s review three days later.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation argued in court filings last week that the Trump administration had failed to take “meaningful steps” toward public review or commission approval.

“They have, repeatedly, broken the rules first and asked for permission later,” wrote lawyers for the National Trust, which sued the Trump administration in an effort to halt construction until required reviews occur.

The White House said meeting with committee staffers and submitting conceptual renderings — rather than detailed blueprints — satisfied the judge’s instruction to start engaging with both commissions by the end of the year.

The National Capital Planning Commission is led by Will Scharf, the White House staff secretary and Trump’s former personal lawyer, whom the president appointed in July. The commission’s membership now tilts heavily toward Trump, including two other White House officials and nine Cabinet members.

The review process for the ballroom building differs markedly from past practice. Large projects have previously undergone lengthy, multistage reviews that begin well before any demolition or site work. Agencies typically engage planning commission staff months or even years in advance, with commissioners and staff evaluating design, siting and environmental impacts at each stage.

The Trump White House has compressed or bypassed some of those steps. Officials plan to complete in months a process that took nearly two years for a White House security fence that was significantly smaller than the ballroom. That project involved five public meetings, during which the commission assessed compliance with federal environmental laws and “the historic and symbolic importance of the White House and the surrounding grounds,” according to planning commission documents.

By contrast, Trump has overseen a three-month transformation of a large chunk of the White House grounds with no planning commission oversight. In mid-September, crews started clearing foliage and cutting down trees. In late October, the president shocked the public by ordering the demolition of the East Wing. And by early December, cranes and pile drivers were operating daily, as crews worked to create the underground infrastructure necessary to support the building, the White House said.

Scharf has asserted that the planning commission review process covers only “vertical” construction — not demolition or site preparation. Critics have disputed that claim, arguing that demolition, site work and construction are inseparable and that the commission’s mandate includes preserving existing historic structures.

Planning commission records show that commissioners during Trump’s first term approved site development plans for projects before work began, including the perimeter fence and a tennis pavilion.

The commission nevertheless adopted Scharf’s argument in the document it published in December outlining its review process, saying the law doesn’t give it authority over “the demolition of buildings or general site preparation.”

Lawmakers and watchdog groups have repeatedly called for more transparency on the estimated $400 million project being funded by private donors — many without disclosing their contributions. Many of the donors the White House has identified — including Amazon, Lockheed Martin and Palantir — have business before the administration, such as seeking future federal contracts or eyeing potential acquisitions. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

The administration has argued that Trump’s decision to rely on private donations spares taxpayers the cost of the project. Sen. Richard Blumenthal (Connecticut), the top Democrat on the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, sent letters last month demanding more information from several attendees of a White House dinner in October to honor ballroom donors.

“The American people are entitled to all the relevant facts about who is funding the most substantial construction project at the White House in recent history,” Blumenthal wrote.

As Fisher spoke on Thursday, protesters gathered on the street below the building where the commission was meeting, denouncing the ballroom project and the process surrounding it.

About 30 people protested the project outside the building where the commission was meeting, said Jon Golinger, democracy advocate at Public Citizen, a government watchdog nonprofit that organized the gathering. Protesters carried handmade signs that read “Stop Ballroom Bribery $$,” “It’s the People’s House!” and “Corruption never looked so TACKY!”

“It’s an abomination,” Golinger said. “It’s a tattoo on the People’s House. It would be a scar for all time.”

The post Trump plans to make his ballroom addition as tall as the White House itself appeared first on Washington Post.