For Thomas Paine, it’s been a sometimes rough afterlife.

A decade after his death in 1809 in New York City, his remains were disinterred and taken to England to be placed in a grand mausoleum. Instead, they languished in a trunk for years, before disappearing.

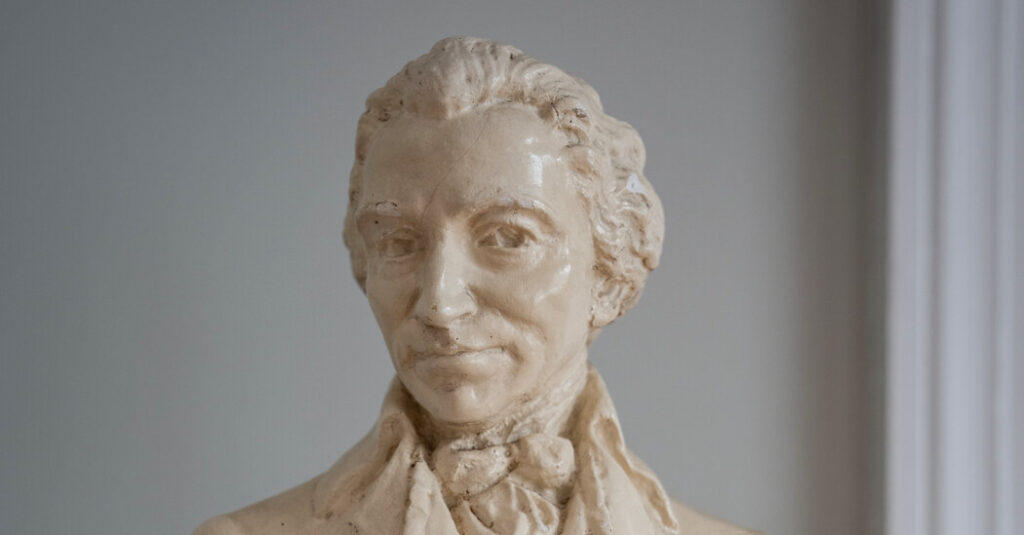

In 1876, a group of admirers offered a newly created bust of him to the city of Philadelphia to be installed at Independence Hall for the nation’s centennial. But the city’s leaders, mindful of Paine’s posthumous reputation as an atheist rabble-rouser, declined it.

Today, as the 250th anniversary of independence approaches, the old grudges have faded. While not as celebrated as Washington, Jefferson and Hamilton, Paine is now comfortably ensconced in cultural memory as a colorful (and quotable) best supporting actor of the Revolution, cited on the left and right as an eloquent tribune of the common man standing against unjust authority.

Paine gets the first word in Ken Burns’s recent 12-hour documentary about the American Revolution. The 250th anniversary of “Common Sense,” his searing broadside in favor of independence, published on Jan. 10, 1776, is being commemorated with conferences, readings and other tributes on both sides of the Atlantic.

And while his bones are still lost, scholars have been putting the full corpus of Paine’s ideas back together. In June, Princeton University Press will publish a six-volume edited collection of his complete works, including nearly 300 previously unknown letters, essays and pamphlets stretching back well before “Common Sense.”

The newly identified early writings, scholars say, complicate the longstanding image of Paine as the undereducated working-class immigrant firebrand who came out of nowhere to write a runaway best seller that transformed a colonial rebellion into a drive for independence.

But they also add fresh texture to a long-running debate: just how revolutionary — and how democratic — was the American Revolution anyway?

An 18th-Century Viral Hit

Paine may not have the pop-culture profile of the A-list founders. But his eventful life — and sometimes bizarre afterlife — has more than enough drama to fill a musical, mini-series or graphic novel (at least one of which exists).

Born in 1737 in Thetford, England, he knocked around as a corset-maker, sailor and tax collector while also mixing in political circles, where he met, and impressed, a visiting Benjamin Franklin. In late 1774, he took off for America, arriving in Philadelphia with a case of typhoid so severe he had to be carried off the ship.

A few months later, Paine became editor of the recently founded Pennsylvania Magazine. Then came the lightning strike of “Common Sense.”

The 47-page pamphlet, attributed simply to “An Englishman,” landed nine months after the battles of Lexington and Concord, when the failed invasion of Quebec had left Americans uncertain what would come next. Some saw reconciliation as a wiser course. But Paine would have none of it, attacking not just George III but the legitimacy of monarchy itself.

“Nothing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined declaration for independence,” he wrote, after demolishing arguments against it. In a free society, he wrote, “the law ought to be king.”

Paine claimed that “Common Sense” sold as many as 150,000 copies in the first three months, an enormous number for a population of about 2.5 million people. Recent research has revised that claim downward, but scholars argue that just about everyone would have encountered his ideas excerpted in newspapers, read aloud around the fireplace and debated in taverns.

“Common Sense” was also not, as Paine claimed, his first book, or his first attack on the monarchy. Among the earlier works unearthed by scholars, via a combination of computer-assisted textual analysis and old-fashioned archival legwork, is a 1773 pamphlet, written with Franklin, defending a London publisher on trial for sedition for criticizing the king.

With “Common Sense,” Paine made the leap from radicalism, which denounced the corruption of the current monarchy, to full-blown republicanism. But Danielle Allen, a professor of government at Harvard and author of a forthcoming book detailing her discoveries relating to Paine’s entanglements in radical circles in England, said the importance of “Common Sense” lay not in its originality but its audacity.

“It’s what political scientists would call breaking the ‘spiral of silence,’ when everyone knows the truth but no one says it out loud,” she said. “The truth everyone knew is America had to be independent. Because someone said it out loud and explained it, it became reality.”

Paine was less enamored of what came after the Revolution. He criticized the U.S. Constitution, with its checks on the will of the people, as insufficiently democratic. In 1787, he returned to England, where he was put on trial in London in 1792, charged with seditious libel for his book “The Rights of Man,” which defended the French Revolution and the broader right of people to overthrow their government.

Trump Administration: Live Updates

Updated

- 5 Democratic states sue the Trump administration over $10 billion funding freeze.

- Amid protests, ICE told agents to take ‘decisive action’ if threatened.

- Trump orders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in mortgage bonds.

Paine was convicted in absentia, having already fled to France, where he was elected to the National Assembly. Two years later, at the height of the Terror, he was imprisoned for opposing the execution of Louis XVI.

Paine was released after the intervention of James Monroe, the ambassador to France. But a year later, feeling slighted, he wrote a scabrous open letter attacking George Washington and his administration as incompetent, corrupt and elitist.

He returned to the United States in 1802 and settled on the farm he had been awarded in New Rochelle, N.Y., a recognition of his contributions to the Revolution. He continued to squabble with local leaders. When he died in 1807, only a handful of people attended his funeral.

For many Americans, he was remembered less as a hero of independence than as the author of the scandalous antireligious tract “The Age of Reason.” In 1819, in a letter to Jefferson, John Adams dismissed “Common Sense” itself as a “poor, ignorant, shortsighted, crapulous mass.”

Debunking the Myths

Today, New Rochelle, an affluent suburb of New York City, is the epicenter of American Paine appreciation. At the preserved Thomas Paine Cottage, a Paine mannequin sits in the parlor, as if pausing between blasts of the pen.

Across the street is the colonnaded headquarters of the Thomas Paine Historical Association, founded in 1894 by a group of freethinkers, anarchists and socialists eager to restore him to his place in history.

A piece of Paine’s brain, acquired by a 19th-century biographer, is said to buried somewhere under a monument to Paine a few steps away. But the real trove of Paine-iana is held down the road at Iona University, where Nora Slonimsky, the director of its Institute for Thomas Paine Studies, laid out some choice items on a recent afternoon.

There were multiple early printings of “Common Sense” and other Paine pamphlets. His writing kit was also there, along with some macabre commemorative coins from his 1792 trial, stamped with an image of him swinging from the gallows.

Slonimsky said that Paine attracts a wide variety of admirers, including younger people who see him as an avatar of passionate self-expression who knew how to go viral.

“Whether it’s because he was an immigrant, because of his opposition to hereditary power or because he had strong opinions and shared them in pamphlets, which feel like what Twitter was a few years ago, people see something there,” she said. “He’s accessible in a way that many other figures of the period are not.”

Still, there remains some defensiveness among Paine-ites. Inside the museum at the historical association’s building, there’s wall text debunking “myths” about Paine, including that he was a drunkard or, as Theodore Roosevelt claimed, a “filthy little atheist.” (In fact, the text notes, he was tidy, a deist and 5 feet 10 inches tall.)

Gary Berton, an independent scholar who has led the association for 30 years and helped edit the forthcoming edition of Paine’s collected works, said that while Paine gets more respect in the academy than he used to, his radically democratic ideas remain embattled. “We are still fighting Paine’s fight,” Berton said.

Well into the 20th century, Paine was seen by some prominent historians as too working class, too emotional, too erratic. Compared with men like Jefferson and Adams, the Harvard scholar Bernard Bailyn wrote in 1990, Paine was “an ignoramus, both in ideas and the practice of politics.”

But Paine has also been a touchstone for historians who see the revolution as a bottom-up affair driven by artisans and working people, free and enslaved, whose democratic longings were betrayed by the elites who disdained and feared them.

“Paine is a Rorschach’s test for how one sees the Revolution and the question of its radicalism,” David Waldstreicher, a historian at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, said.

In the realm of politics, Paine has gone from being an icon of the left to part of the shared stock of founders. Accepting the Republican nomination for president in 1980, Ronald Reagan quoted “Common Sense,” declaring “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.”

In 2009, the heyday of the Obama-era Tea Party, Glenn Beck donned breeches and wig in a comedy tour to promote “Glenn Beck’s Common Sense,” his Paine-inspired best seller assailing “out-of-control government.”

Today, Paine’s words have appeared at the “No Kings” protests, which cast President Trump as a new George III. But some also see echoes of his spirit on the populist right, with its hostility to elite institutions.

In his 2014 book “The Great Debate,” Yuval Levin, a political theorist at the American Enterprise Institute, traced America’s left-right divide to Paine’s debates with Edmund Burke over the French Revolution. But in current American politics, he says, populist vs. elitist is more important than progressive vs. conservative.

“Today, the right is populist, and how old something is is not necessarily an argument in its favor,” he said. “And that view, which is Paine’s, is deeply American.”

Allen, the Harvard professor, said Paine’s legacy shouldn’t be judged by who claims his mantle or tends his monuments. Instead, it lies in the enduring hold of his ideas of what guarantees a free society: the supremacy of an elected legislature, and the bedrock idea that the law is king.

“The question of his legacy is: Are these things still true in America?” she said.

Jennifer Schuessler is a reporter for the Culture section of The Times who covers intellectual life and the world of ideas.

The post The Many Lives of a Radical Founder appeared first on New York Times.