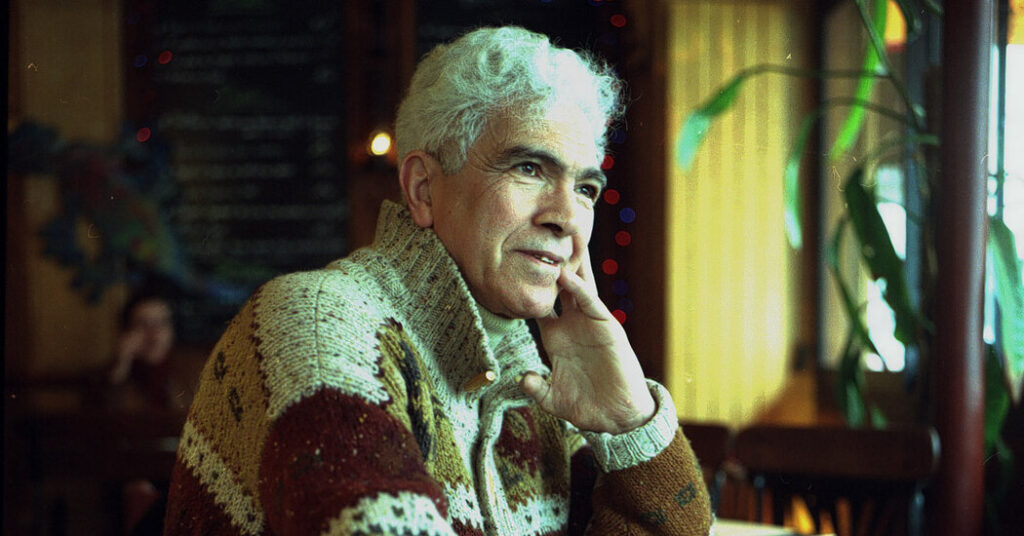

Mohammed Harbi, a maverick historian of Algeria whose perspective — that of an insider turned outsider — shattered myths about his country’s break from France, died on Jan. 1 in Paris. He was 92.

His death, in a hospital, was confirmed by his son Emir.

Mr. Harbi saw Algeria’s bloody split with France from within, as a high official in the early revolutionary government. Then, when he denounced widespread torture and other abuses, he was imprisoned after the military seized power in 1965, before escaping into exile after a period of house arrest and beginning a long second career as a historian who rewrote the story of his country’s flawed independence.

Among many left-leaning Western observers and in the developing world, its revolution, which led to independence in 1962, was seen as an exemplary anticolonial struggle, paving the way for other nations shaking off the old imperial order. Algiers, the capital, became a beacon for artists and intellectuals, as well as a magnet for the Black Panthers and other activists.

Breaking with that rosy-eyed view, Mr. Harbi was the first to demonstrate that the Algeria of today — closed, repressive, authoritarian and governed by the military — had its roots in the country’s troubled birth.

“Usually, every country has an army,” Mr. Harbi was fond of saying. “In Algeria, it is the opposite: It’s the army that has the country.”

He was “the most brilliant and implacable historian of independent Algeria,” the French historian Pierre Vermeren said in Le Figaro newspaper last week, after Mr. Harbi’s death. In another tribute, in the magazine L’Histoire, the historian Benjamin Stora said that Mr. Harbi was a “pioneer in deconstructing the official ideology.” In a 2003 New York Times profile, Adam Shatz called him “Algeria’s most renowned intellectual.”

In “The Origins of the F.L.N.” (1975), the French acronym for the ruling National Liberation Front, and “The F.L.N.: Mirage and Reality” (1980), both begun during his imprisonment and completed in exile, Mr. Harbi, using documents he had patiently assembled for several decades, demonstrated that the revolutionary F.L.N. party was not really a political party at all.

Instead, the movement that led Algeria to independence, and continued to lead it for six decades after, was a collection of militaristic, warring factions, each intent on extracting the maximum benefit for its constituents by exploiting a patriarchal, hidebound country that remained deeply Muslim.

Mr. Harbi was in a position to know about this intimately. He had grown up in a prosperous family of rural landowners with no feelings of deference toward the French colonizers. Later, he was a key adviser to both the man who signed the peace accords with France, Krim Belkacem, and Algeria’s first president, Ahmed Ben Bella.

“In the days after the cease-fire” with France, Mr. Harbi wrote in “Une Vie Debout: Mémoires Politiques” (2020, not translated), “behind the divided forces of the armed resistance, what stirred above all were groups of partisan camp followers seeking rewards, and with no other goal but the personal appropriation of the colonial heritage left behind by the fleeing Europeans.”

Decades later, little has changed. The F.L.N., along with the army, still runs the country, though the current president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, nominally left the party in 2019. Mr. Harbi’s books were banned in Algeria until the early 1990s; he did not return to his homeland, from long self-exile in Paris, until 1991.

“We won our independence,” Mr. Harbi told Le Monde in an interview in Paris in 2019, as a rare protest movement was unfolding in Algeria, “but we left behind one crisis to enter into another. The militarization of our society took place because of these crises.”

“Our independence was stolen,” he added, “by armed men who have robbed the inhabitants of their country.”

Mohammed Harbi was born on June 16, 1933, in El Harrouch, in eastern Algeria. He was the eldest of seven children of Brahim and Aicha (Kafi) Harbi. His father came from a family of well-to-do landowners and was himself a successful farmer.

By the age of 6, Mr. Harbi was attending the local French school, and he later went to high school at the Collège Dominique-Luciani in the town of Skikda, where he was strongly influenced by his history teacher, Pierre Souyri, a leftist Frenchman who had been in the Resistance during World War II.

By 15, Mr. Harbi had joined the leading pre-independence nationalist movement in Algeria, Messali Hadj’s Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties, earning him the ire of what he later called his “accommodationist” family. He completed high school at the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris and entered the Sorbonne in 1953 to study history.

With the outbreak of war in Algeria the following year, he became active in Muslim student unions in Paris and signed on with French units of the F.L.N. The party’s cadres noticed him, and he became an adviser to Mr. Belkacem, the F.L.N. foreign minister, who in 1960 sent him as the movement’s ambassador to Guinea, then at the forefront of African revolutionary nationalism for demanding full independence from France.

After Algeria won its independence, the new president, Mr. Ben Bella, persuaded Mr. Harbi to stay close to the center of power, but he was becoming increasingly disillusioned, publicly denouncing the widespread official use of torture.

Mr. Ben Bella was deposed in a coup in June 1965, launched by the army chief of staff Houari Boumédiène. Mr. Boumédiène proposed several possible positions to Mr. Harbi, who refused.

“I don’t want anything to do with you,” he recalled saying in the Le Monde interview. “You’ve seized power, you’ve got an agenda, it’s got nothing to do with me.”

He was put in a roughly 21-square-foot cell with a soggy mattress. Moved from prison to prison, at one point he found himself in France’s old torture center, the Villa Bengana in Algiers.

His first book was written largely during this period. “Without that, I wouldn’t have made it,” he later wrote.

In 1969, he was placed under house arrest in his home province. Two years later, with the help of a fake Turkish passport, he fled across the frontier to Tunisia, and in 1973 he reached France, where he was to spend the rest of his life, much of it in a modest apartment in the working-class Belleville neighborhood of Paris.

Mr. Harbi is survived by three sons, Emir, Jamil and Reda, and a daughter, Mona. He and his wife, Djenett (Regui) Harbi, separated in 1977.

Like many other Algerian exiles, he was hopeful about the young people’s protest movement known as Hirak that blossomed, briefly, in 2019 before being snuffed out.

“They’ve never known independence,” he told Le Monde. “They believe that French domination was simply replaced by the domination of the Algerian army. And that began in 1962. And so when they saw that the F.L.N. hadn’t kept its promises, they said, ‘It’s as though the French never left.’”

Adam Nossiter has been bureau chief in Kabul, Paris, West Africa and New Orleans and is now a writer on the Obituaries desk.

The post Mohammed Harbi, Who Rewrote Algeria’s History, Dies at 92 appeared first on New York Times.