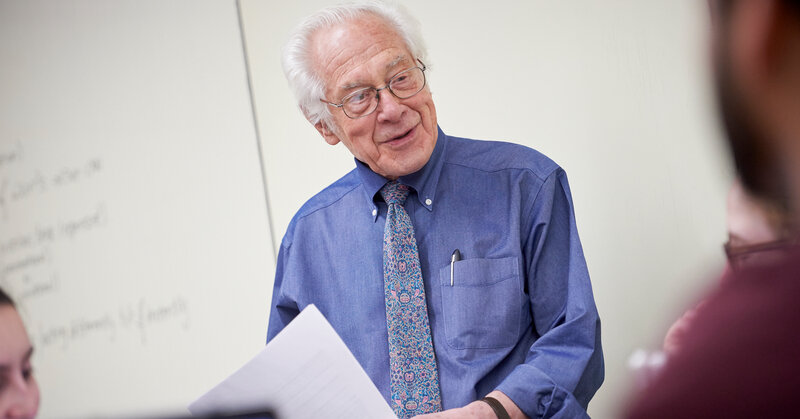

Jerome Lowenstein, a distinguished professor of medicine at New York University who in an artistic sideline helped found a literary journal and a small publishing imprint that drew book-world attention when it published a debut novel that won a Pulitzer Prize after being rejected by many other editors, died on Dec. 8 at his home in Manhattan. He was 92.

His son, Benjamin, also a physician, confirmed the death.

Over more than 60 years, Dr. Lowenstein guided young doctors at the N.Y.U. Grossman School of Medicine to take a more humanistic approach to patient care; performed groundbreaking research as a kidney specialist; and published books of his own, including a medical work largely about nephrology, a scientific novel set during World War I, and a collection of essays about medicine.

His detour into literature began in 2000, when he was asked by Martin Blaser, the chairman of N.Y.U.’s department of medicine, to join him and Danielle Ofri, who had worked with Dr. Lowenstein when she was a resident at N.Y.U., to start the Bellevue Literary Review. Its name was a homage to the historic municipal hospital in Manhattan where all three had worked.

The Review, a twice-yearly journal, specializes in narratives about illness and health, publishing fiction and nonfiction at the intersection of arts and science. Dr. Lowenstein was its nonfiction editor for 20 years.

“He was an active editor, choosing pieces and thinking about the path of the journal and who we brought in,” Dr. Ofri, the editor in chief, said, adding: “He was a mensch, always patient and thoughtful.”

When he stepped down from the journal in 2021, Dr. Lowenstein, in an article there, recalled the wide range of nearly 1,000 manuscripts that had poured in after the editors solicited submissions through classified ads in three writing magazines.

“Some dealt with terminating dialysis treatment; others described coping with chemotherapy or how it feels to be psychotic,” he wrote. “A few were lighter, like the story of a medical intern called upon to repair the gurgling toilet in his landlady’s upstairs apartment.”

In 2007, Dr. Lowenstein added another title: publisher of the Bellevue Literary Press. He worked with Erika Goldman, the editorial director, who had edited his novel, “Henderson’s Equation” (2008).

She also knew Dr. Lowenstein from observing his compassionate care of her parents.

“I was awe-struck by how he ministered to them,” Ms. Goldman said in an interview. “For me to shift gears and work with him as an editor was jarring at first.”

Dr. Lowenstein, who raised about $500,000 from private donors to finance the press, read portions of books that Ms. Goldman wanted to publish, including “Tinkers,” a melancholy first novel by Paul Harding about the deathbed memories of a New England clock repairer. Before being published by Bellevue, it had been rejected by some three dozen publishers and agents.

In 2010, “Tinkers” won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, the first time a novel published by a small press had won the award since “A Confederacy of Dunces,” by John Kennedy Toole, in 1981.

The award instantly elevated Mr. Harding’s career. Within an hour of the Pulitzer announcement, Random House sent out a news release saying that it had signed a two-book deal with him in 2009. A few days later, the Guggenheim Foundation awarded him a fellowship. The novel spent 32 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list (though The Times had declined to review it).

“Jerry was incredibly generous and thoughtful with compliments about the book,” Mr. Harding said in an email. “Even though my second novel, ‘Enon,’ came out with a different publisher, he wrote me a kind letter about it, in which he said it made him feel as if he was journeying through the literary equivalent of Berlioz’s ‘Symphonie Fantastique’ — one of my all-time favorite reader responses.”

Jerome Lowenstein was born on Jan. 25, 1933, in the Bronx. His father, Samuel, an immigrant from Russia, worked in a brokerage house and owned a bar in Lower Manhattan. His mother, Fay (Shapain) Lowenstein, managed the home and helped in the bar.

Young Jerome didn’t want to be a storekeeper, a lawyer or a dentist and couldn’t stand the sight of blood because of childhood nosebleeds. He set his sights on becoming an eye doctor — which he felt would be bloodless — and entered N.Y.U. to study optometry.

He eventually shifted to pre-med studies, however, and received a bachelor’s degree in 1953. After graduating from the N.Y.U. College of Medicine in 1957, he interned at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx; studied gerontology for two years at the National Institutes of Health in Baltimore; served his residency at Bellevue Hospital; and returned to N.Y.U. in 1963, where he became an acolyte of Dr. Lewis Thomas, a dean of the school of medicine who was renowned for his elegant books demystifying biology. Dr. Lowenstein’s foundational research on renal physiology included studies of the kidney’s relationship to high blood pressure.

He found a special joy in teaching, but came to learn that some of his students, interns and residents struggled emotionally with their grueling medical educations.

After one of his occasional dinners with a group at his home in the late 1970s, two interns confessed that despite excelling at their work, they felt that they had just endured the hardest period of their lives.

“Each of them, in a way, they had to give up a great deal of their own humanity to do as well as they did, to be as efficient and get as much done, and they found that very painful,” Dr. Lowenstein recalled in an oral history interview with N.Y.U. in 2015.

“I sort of heard that,” he said, “but not the way my wife did. She had just graduated and gotten her master’s in social work.”

When the interns had left, his wife, Lois, asked him, “What do you do for these people?”

He replied, “What do you mean?”

She told him, “They’re obviously in pain. What do you do for them?”

The solution she suggested was to meet regularly with small groups of them and discuss their experiences with patients.

With funding from the hospital, and then from a major donor, Bernard Schwartz, who ran Loral, a defense contractor, Dr. Lowenstein established the Program for Humanistic Aspects of Medical Education. It hosted weekly seminars in which students, interns and residents could discuss their demanding work lives and reflect on their relationships with colleagues and patients.

“With the benefit of countless anecdotes about the effects of these seminars on the lives and attitudes of physicians,” Dr. Lowenstein wrote in a letter to the editor of The New York Times in 2002, “we have come to believe that strategies that allow physicians to cope with the cumulative burden of pain, grief and suffering are best learned in the context of their medical education.”

He continued to run the program until it was discontinued in 2022 and integrated into other parts of N.Y.U. He retired in 2024.

In addition to his son, Dr. Lowenstein is survived by his wife, Lois (Goldstein) Lowenstein; six grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. His daughter, Lissa Florman, died in 2010.

In his 1997 book, “The Midnight Meal and Other Essays About Doctors, Patients and Medicine,” Dr. Lowenstein wrote about the need for doctors to show compassion, which he defined in part as “the willingness to enter into a relationship in which not only the knowledge but the intuitions, strengths and emotions of both the patient and the physician can be fully engaged.”

While he argued that compassion can be developed early in life, he also acknowledged that it can erode during medical training, resulting in “a learned insensitivity to the pain and suffering and the needs of patients.”

Teaching compassion is as important as teaching medicine, he wrote.

To those who disagreed, he added: “I would view them in the same way I view a teacher of medicine who rejects the idea of teaching physical diagnosis or pathophysiology. This person might be a gifted and valuable teacher, but this outlook is a distinct limitation.”

Richard Sandomir, an obituaries reporter, has been writing for The Times for more than three decades.

The post Jerome Lowenstein, 92, Dies; Teaching Doctor With a Literary Sideline appeared first on New York Times.