When he designed and built his home sweet home, one thing mattered most for the Turkish architect Onurcan Cakir: quiet. But it wasn’t solely because he craved blissful silence.

His house, located in southwestern Turkey, is made from dense materials that block noise from outside. Double doors and heavy windows are sealed tightly, preventing gaps that could admit sound. One of the three bedrooms — a kind of “panic room” for times when outside noise is especially jarring — has extra-thick walls.

Such principles would work for anyone seeking unbothered tranquility. Cakir, however, created his house as a case study not just for those who crave an acoustic paradise — but for those seeking quiet as a medical necessity, as he does, for a rare auditory disorder.

When the house was finished 10 years ago, Cakir received some recognition in architectural and design publications — both for his home’s natural materials and for its unique acoustic qualities. Now, in a recent paper published in “Civil Engineering and Architecture,” Cakir describes a “Silent House Typology” — architectural principles to create a home as quiet as possible.

One aim, he said, was to delineate guidelines that could benefit others who must also control their sound environment.

In 2009, as a music student working with high volumes through headphones, Cakir suffered a noise injury, sometimes called acoustic trauma. He ended up with tinnitus, or ringing ears, as well as the sound sensitivity known as hyperacusis, where ordinary sounds are perceived as agonizingly loud.

“Since that time, I have had to protect myself against daily sounds,” he told The Post. “People do not understand how hard it is to have pain because of sound. I don’t leave the house without earplugs.”

Back then, Cakir’s severe form of hyperacusis was so little known that there wasn’t even a term for it.

But within the past few years, that severe form has been distinguished as pain hyperacusis, sometimes called noxacusis, where everyday sounds cause stabbing, burning, lingering ear pain. Cakir’s greatest difficulty comes from digital, electronic or artificially amplified sound.

Over time, with the help of the internet, he learned that “there are people around the world having almost the same problems and feeling almost the same things as me, which made me feel more confident about my condition and made me feel not so lonely,” he told The Post.

Unwanted sound is an annoyance for so many and a health risk for some, with negative effects on cardiovascular function as well as on hearing, said Steven Barad, a retired medical doctor and president of the nonprofit Hyperacusis Research, which funds research into noise-induced pain.

“Home should be a sanctuary, but a home is generally not quiet unless someone makes it quiet,” he told The Post. “We hear from people who move multiple times seeking quiet.”

Still, they generally trade one uncontrolled noise for another. “In suburbia, even people without hearing problems suffer so much from motorized lawn equipment that some municipalities are restricting leaf blowers,” he said. “In apartment buildings, with shared walls, noise from surrounding neighbors is a major source of conflict.”

But Barad contests the notion that the world’s quietest house is in Turkey. It may be in northern California, occupied by his 34-year-old son, who as a teenager had a severe acoustic injury from loud music.

“My son’s house is in a remote location, with soundproof windows,” he said. “Even so, it is impossible to block all noise.” His son still must endure distant traffic, crowing roosters and drumming woodpeckers.

“Unfortunately, not everyone with pain hyperacusis can afford to live in a sufficiently quiet environment,” Barad said, “and they must control the surrounding noise the best they can.”

Cakir found that his native Istanbul — Europe’s largest city with a population of roughly 16 million — was unlivably noisy. Airplanes droning overhead made it hard to sleep. Low bass, which is especially hard to block, bled through his apartment walls, where neighbors were either partying students or hard-of-hearing seniors with blaring televisions. “Everyone watches TV and it is considered normal to leave the TV on during the day,” he said.

So he moved to a small village called Barbaros, near Izmir on the Aegean Sea. He now works as an associate professor at Izmir Democracy University, specializing in architectural acoustics.

Some types of buildings take acoustics into account — concert halls being a prime example — but acoustic comfort is routinely neglected when it comes to homes. Residential building codes rarely account for noise transmission.

“It is generally easier to start from scratch instead of trying to find and correct all the problematic parts of an existing building,” Cakir said.

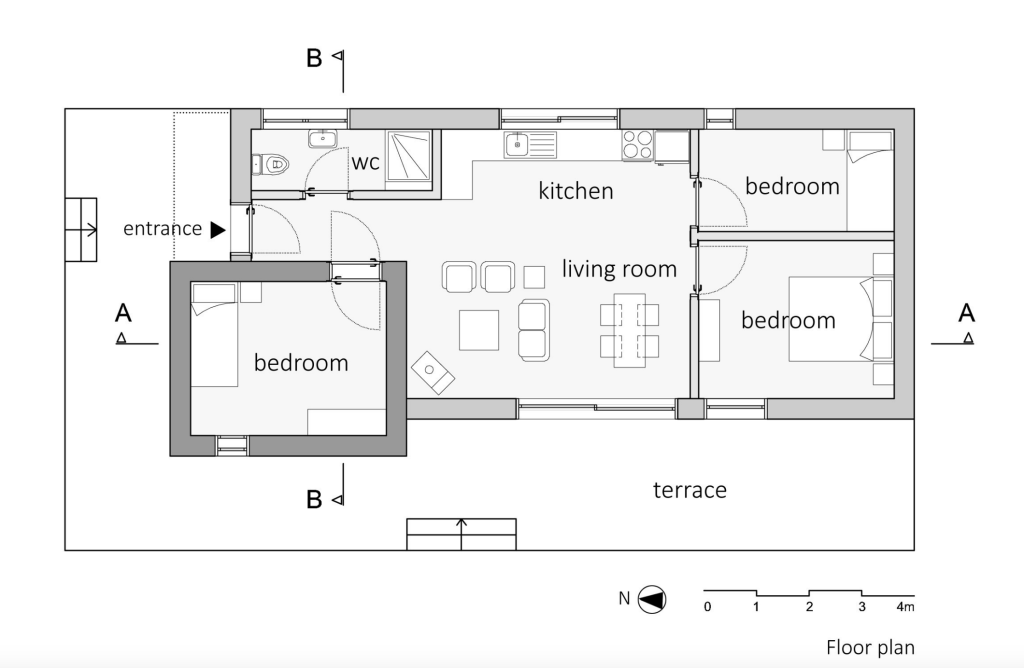

To block outdoor noise, his detached house, just 900 square feet, has dense exterior walls — 20 inches thick — made of stone, brick and insulation. The panic room is reinforced with concrete and layered with air cavities and mineral wool, often called rockwool. It includes double doors and triple-paned windows with layers of air between the panes, which dull sound transmission.

“I believe there is a misunderstanding about soundproofing even by architects,” Cakir said. Flexible connections between building elements are needed to avoid transferring vibration. Windows and doors must be airtight, without even the tiniest gap.

Just as water can seep through any gap, so can sound. “When there’s a small gap, most of the extensive insulation you’ve done goes to waste,” Cakir said.

Indoors, however, echo can be easily reduced with soft furnishings and rugs, which absorb sound and reduce reverberation time.

Even in Cakir’s small village, with little street traffic and a population of 400, wedding celebrations take place within earshot.

Turkish weddings often happen in a village square. “Everyone knows one another and villagers enjoy celebrating together,” Cakir said. So he stays in his silent bedroom for the duration, with doors and windows shut.

His village is also known for the annual Barbaros Scarecrow Festival. When it began in 2016, Cakir was invited to participate, so he took charge of the music. “I called it ‘unplugged street music,’ without any electricity or loudspeakers,” he said. “So it was a very nice festival in its first year.”

But the festival grew and things changed. The music is now amplified. During the festival, Cakir either remains sheltered at home or leaves.

To avoid processed sound on a television or computer, he always uses subtitles. He avoids restaurants and cafes, due to intolerable background music.

Cakir, now 39, lives in his quiet house with his wife — also an architect, whom he met at a workshop for natural building materials — and their 3-year-old daughter, along with two dogs that rarely bark.

“There is a thing for children called ‘Gabby’s Dollhouse,’” Cakir said. “I had to learn about that now that I have a 3-year-old daughter. When she goes to her grandmother’s she can listen to these things, but when she is at home she does not.” Instead, she watches TV with subtitles, even though she cannot yet read.

“Luckily, my little girl is very understanding and aware that everyone in the house must be quiet,” Cakir said. “It’s weird, I know, but we manage to live together somehow.”

Most importantly, “I can control the noise inside a single-family house,” he said. “It’s not attached to another house so I don’t have the problem of neighbor noises through the wall. Having respectful and understanding neighbors is a matter of chance, as they will be one of the main noise sources.”

The post Inside the quietest home in the world — which a Turkish architect built for himself out of medical need appeared first on New York Post.