Hessy Levinsons Taft, who as an infant appeared on the cover of a Nazi magazine in Germany promoting her as the ideal Aryan baby, a distinction complicated by the fact that she was Jewish and had been exploited as part of a dangerous hoax, died on Jan. 1 at her home in San Francisco. She was 91.

Her death was confirmed by her family.

Terrifying at first, the story eventually became a source of pride for Mrs. Taft and her parents for the way it neatly illustrated the absurd pseudoscience underlying Adolf Hitler’s racial ideology.

“I feel a sense of revenge,” she said much later. “Good revenge.”

The episode began in 1934, when Hessy was 6 months old and her parents, Latvian opera singers living in Berlin, hired the well-known photographer Hans Ballin to take her portrait.

After framing the photo, her parents displayed it on their piano. One day, the woman who cleaned their home noticed it and told Hessy’s mother that she had seen her daughter on the cover of a magazine.

“My mother thought surely she must be mistaken, that there are many babies that look alike, and just told her, ‘Well, that couldn’t be the case,’” Mrs. Taft said in an interview with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1990.

The woman insisted that it was the same baby. “Just give me some money,” she said, “and I’ll get you the magazine.”

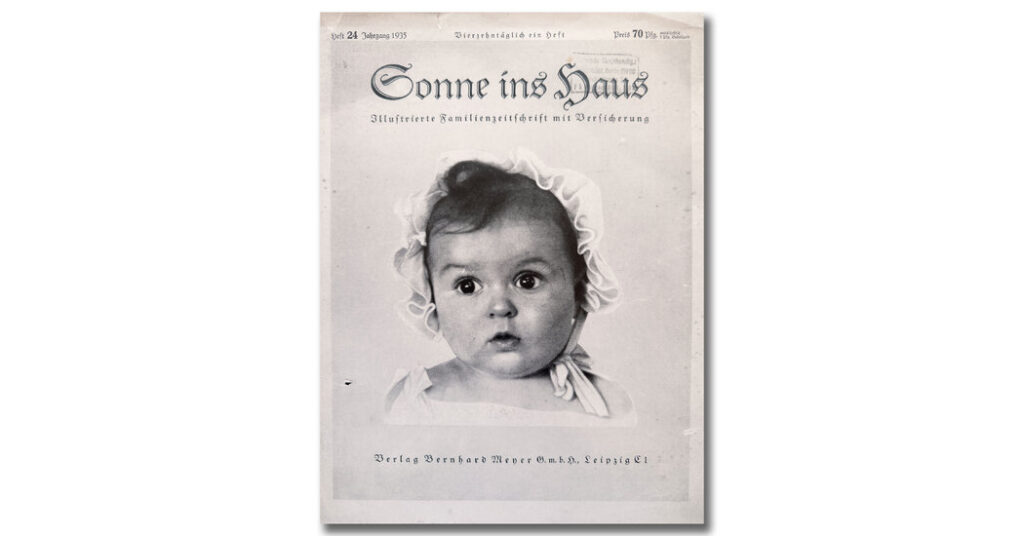

Soon she returned with a copy of Sonne ins Haus, or Sun in the Home, one of several pro-Nazi magazines that were allowed to circulate in the country after Hitler had shut down thousands of other publications. And there, on the cover, was the portrait from the piano.

Hessy’s mother flipped through the pages.

“On the inside of the magazine were pictures of the army with men wearing swastikas,” Mrs. Taft told the Holocaust museum. “My parents were horrified.”

Her mother went to Mr. Ballin’s studio and showed him the magazine. “What is this?” she said. “How did this happen?”

He told her that the Nazis had invited him to submit photos for a contest to find a baby representing the epitome of the Aryan race, and Hessy was among those he included in his submission. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of public enlightenment and propaganda, chose the winner.

“But you knew that this is a Jewish child,” Hessy’s mother told the photographer.

He replied, “I wanted to allow myself the pleasure of this joke.”

Then he added: “You see, I was right. Of all the babies, they picked this baby as the perfect Aryan.”

Suddenly, the photo was everywhere: in advertisements for baby clothes, on postcards, hanging in people’s homes.

“My parents were both shocked by the possible consequences that this could bring and amazed at the irony of it all,” Mrs. Taft said.

As Latvians, her parents were protected from laws targeting Jews of German descent. Still, they were terrified that the Nazis would discover what had happened and execute them. They kept Hessy inside, rarely taking her out, even for walks.

In 1937, as Hitler tightened his grip on Germany, the family moved back to Latvia. Fearing the Nazis or their sympathizers would seek retribution if they learned the truth about the photo, they resolved to keep what had happened a secret.

As her parents advanced in age, Mrs. Taft finally revealed the harrowing tale in the 1987 book “Muted Voices: Jewish Survivors of Latvia Remember,” an essay collection edited by the Holocaust survivor and historian Gertrude Schneider.

“It is the story of a Jewish baby selected by loyal Nazis to serve as an archetypal example of the Aryan race, the theory which the Nazis’ leadership seized every opportunity to promote,” Mrs. Taft wrote. “I was that baby.”

Hessy Lewinsohn was born on May 17, 1934, in Berlin. Her father, Jacob Lewinsohn, was a baritone opera singer; her mother, Pauline (Levine) Lewinsohn, sang soprano. (The spelling of the family’s surname was eventually changed to Levinsons.)

After marrying in Latvia, her parents moved to Germany in 1928 to pursue careers in the opera, but their Jewish-sounding surname made finding work difficult. For guidance, they visited the Latvian consulate in Berlin.

“The consul,” Mrs. Taft wrote, “assured my parents that Hitler would not last. He advised them to stay in Berlin until Hitler fell and then they could resume their singing careers.”

Her father got a job representing a Latvian company in Berlin and became successful enough that the family could afford a nice apartment on Augsburger Strasse, a prestigious street in the city.

“But things were very, very tenuous,” Mrs. Taft said.

They finally left Berlin, returning briefly to Latvia before settling in Paris. When the Nazis occupied that city in 1940, they fled again, first to Nice and then to Cuba, where Hessy attended a British school. In 1949, they moved to New York City.

She received a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Barnard College in 1955 and a master’s from Columbia University in 1958. The following year, she married Earl Taft; he died in 2021.

For more than 30 years, Mrs. Taft worked for the Educational Testing Service in Princeton, N.J., overseeing advanced placement chemistry exams for high school students. At age 66, with no interest in retiring, she joined the faculty of St. John’s University in Queens as an adjunct professor, teaching chemistry and conducting research on water sustainability.

She is survived by her children, Nina and Alex Taft; four grandchildren; and a sister, Noemi Pollack.

The Levinsons family kept three copies of the magazine. Mrs. Taft donated one to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1990 and another to Yad Vashem, Israel’s official Holocaust memorial center, in 2014. Her children kept the last copy.

After going public with her story, Mrs. Taft was often asked what she thought of the photographer’s prank.

“I can laugh about it now,” she told Tablet magazine in 2022. “But if the Nazis had known who I really was, I wouldn’t be alive.”

In fact, she said, she was grateful to the photographer.

“I thank him for having the courage to do that, as a non-Jew, to challenge his own government,” she told Reuters. “It was an irony that needed to be exposed.”

The post Hessy Levinsons Taft, Jewish Baby on Cover of Nazi Magazine, Dies at 91 appeared first on New York Times.