Federal Reserve officials will likely need to see more notable signs of a labor market slowdown if they are to lower interest rates again after a series of reductions last year.

On Friday, central bankers will get a clearer read on where things stand with the release of December’s jobs report. That report has taken on new significance because of the recent dearth of data stemming from the government shutdown last fall.

In November, the unemployment rate rose more than expected to a four-year high of 4.6 percent, a jump that, if sustained, would be a warning sign about how the economy is faring.

Most economists polled by Bloomberg expected the unemployment rate in December to have slipped to 4.5 percent, higher than at the start of last year but still relatively low by historical standards.

What the Fed is trying to figure out is how much more support to provide the economy at a time when inflation is still well above its 2 percent target. Several officials opposed the central bank’s decision last month to cut borrowing costs by a quarter of a percentage point, the third straight reduction of that size.

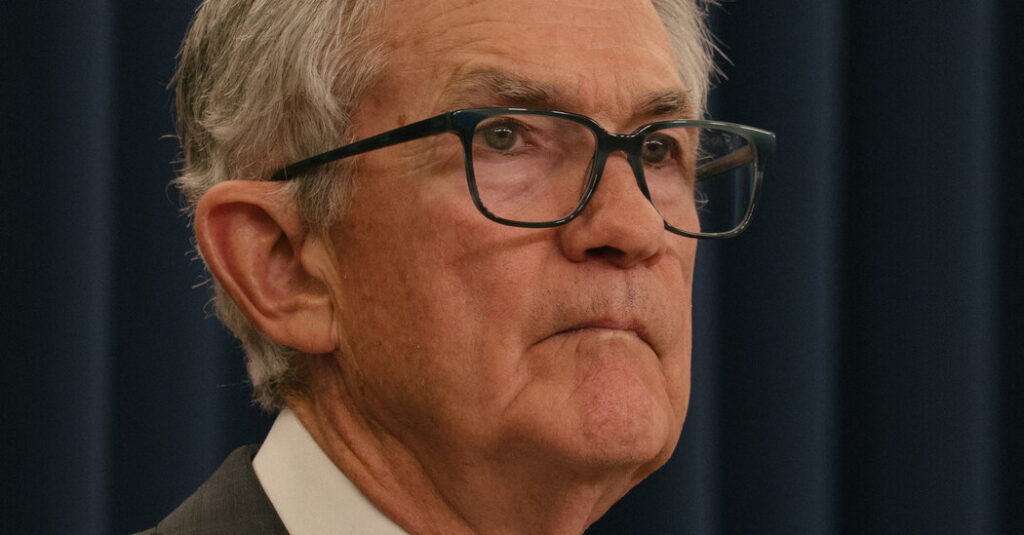

After December’s cut, which brought rates down to a range of 3.5 percent to 3.75 percent, Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, said the central bank was “well positioned to wait to see how the economy evolves.”

That conveyed little urgency to deliver another reduction when the Fed gathers for its first meeting of the year on Jan. 27-28. A new set of presidents from some of the 12 regional reserve banks will join the 12-person Federal Open Market Committee, which votes on policy decisions. They are Beth M. Hammack of the Cleveland Fed, Lorie K. Logan of the Dallas Fed, Neel T. Kashkari of the Minneapolis Fed and Anna Paulson of the Philadelphia Fed.

Ms. Hammack and Ms. Logan have previously indicated that they did not support all of the Fed’s rate cuts last year, while Mr. Kashkari recently said that the central bank was close to the point where it did not need to cut further. Even Ms. Paulson, who has expressed concerns about the labor market, indicated that the Fed did not need to hurry to cut.

According to projections released alongside the December rate decision, seven of the 19 policymakers penciled in no reductions at all in 2026, while eight wanted at least two. Most officials expected the unemployment rate to peak at 4.5 percent in 2025 before edging lower to 4.4 percent in 2026. They expected some improvement in inflation over the course of this year, but not enough to reach their 2 percent target.

Putting rate cuts on pause is bound to anger President Trump, who wants significantly lower borrowing costs and has railed on the central bank for refusing to comply. Mr. Trump is in the process of selecting a new chair to replace Mr. Powell when his term ends in May. In an interview with The New York Times this week, the president said he had made up his mind on his selection but stopped short of disclosing a name.

Kevin A. Hassett, Mr. Trump’s top economic adviser, is seen as the front-runner, but Mr. Trump has also met with Kevin M. Warsh, a former Fed governor who almost got the job in the president’s first administration, and Christopher J. Waller, a current Fed governor.

Colby Smith covers the Federal Reserve and the U.S. economy for The Times.

The post Fed Keeps Close Eye on Labor Market as It Assesses Further Cuts appeared first on New York Times.