Editor’s note: This work is part of AI Watchdog, The Atlantic’s ongoing investigation into the generative-AI industry.

On Tuesday, researchers at Stanford and Yale revealed something that AI companies would prefer to keep hidden. Four popular large language models—OpenAI’s GPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Google’s Gemini, and xAI’s Grok—have stored large portions of some of the books they’ve been trained on, and can reproduce long excerpts from those books.

In fact, when prompted strategically by researchers, Claude delivered the near-complete text of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, The Great Gatsby, 1984, and Frankenstein, in addition to thousands of words from books including The Hunger Games and The Catcher in the Rye. Varying amounts of these books were also reproduced by the other three models. Thirteen books were tested.

This phenomenon has been called “memorization,” and AI companies have long denied that it happens on a large scale. In a 2023 letter to the U.S. Copyright Office, OpenAI said that “models do not store copies of the information that they learn from.” Google similarly told the Copyright Office that “there is no copy of the training data—whether text, images, or other formats—present in the model itself.” Anthropic, Meta, Microsoft, and others have made similar claims. (None of the AI companies mentioned in this article agreed to my requests for interviews.)

The Stanford study proves that there are such copies in AI models, and it is just the latest of several studies to do so. In my own investigations, I’ve found that image-based models can reproduce some of the art and photographs they’re trained on. This may be a massive legal liability for AI companies—one that could potentially cost the industry billions of dollars in copyright-infringement judgments, and lead products to be taken off the market. It also contradicts the basic explanation given by the AI industry for how its technology works.

AI is frequently explained in terms of metaphor; tech companies like to say that their products learn, that LLMs have, for example, developed an understanding of English writing without explicitly being told the rules of English grammar. This new research, along with several other studies from the past two years, undermines that metaphor. AI does not absorb information like a human mind does. Instead, it stores information and accesses it.

In fact, many AI developers use a more technically accurate term when talking about these models: lossy compression. It’s beginning to gain traction outside the industry too. The phrase was recently invoked by a court in Germany that ruled against OpenAI in a case brought by GEMA, a music-licensing organization. GEMA showed that ChatGPT could output close imitations of song lyrics. The judge compared the model to MP3 and JPEG files, which store your music and photos in files that are smaller than the raw, uncompressed originals. When you store a high-quality photo as a JPEG, for example, the result is a somewhat lower-quality photo, in some cases with blurring or visual artifacts added. A lossy-compression algorithm still stores the photo, but it’s an approximation rather than the exact file. It’s called lossy compression because some of the data are lost.

From a technical perspective, this compression process is much like what happens inside AI models, as researchers from several AI companies and universities have explained to me in the past few months. They ingest text and images, and output text and images that approximate those inputs.

But this simple description is less useful to AI companies than the learning metaphor, which has been used to claim that the statistical algorithms known as AI will eventually make novel scientific discoveries, undergo boundless improvement, and recursively train themselves, possibly leading to an “intelligence explosion.” The whole industry is staked on a shaky metaphor.

The problem becomes clear if we look at AI image generators. In September 2022, Emad Mostaque, a co-founder and the then-CEO of Stability AI, explained in a podcast interview how Stable Diffusion, Stability’s image model, was built. “We took 100,000 gigabytes of images and compressed it to a two-gigabyte file that can re-create any of those and iterations of those” images, he said.

One of the many experts I spoke with while reporting this article was an independent AI researcher who has studied Stable Diffusion’s ability to reproduce its training images. (I agreed to keep the researcher anonymous, because they fear repercussions from major AI companies.) Above is one example of this ability: On the left is the original from the web—a promotional image from the TV show Garfunkel and Oates—and on the right is a version that Stable Diffusion generated when prompted with a caption the image appears with on the web, which includes some HTML code: “IFC Cancels Garfunkel and Oates.” Using this simple technique, the researcher showed me how to produce near-exact copies of several dozen images known to be in Stable Diffusion’s training set, most of which include visual residue that looks something like lossy compression—the kind of glitchy, fuzzy effect you may notice in your own photos from time to time.

Above is another pair of images taken from a lawsuit against Stability AI and other companies. On the left is an original work by Karla Ortiz, and on the right is a variation from Stable Diffusion. Here, the image is a bit further from the original. Some elements have changed. Instead of compressing at the pixel level, the algorithm appears to be copying and manipulating objects from multiple images, while maintaining a degree of visual continuity.

As companies explain it, AI algorithms extract “concepts” from training data and learn to make original work. But the image on the right is not a product of concepts alone. It’s not a generic image of, say, “an angel with birds.” It’s difficult to pinpoint why any AI model makes any specific mark in an image, but we can reasonably assume that Stable Diffusion can render the image on the right partly because it has stored visual elements from the image on the left. It isn’t collaging in the physical cut-and-paste sense, but it also isn’t learning in the human sense the word implies. The model has no senses or conscious experience through which to make its own aesthetic judgments.

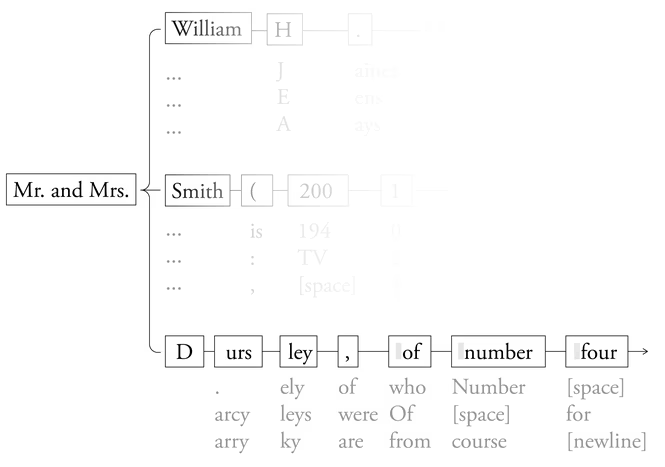

Google has written that LLMs store not copies of their training data but rather the “patterns in human language.” This is true on the surface but misleading once you dig into it. As has been widely documented, when a company uses a book to develop an AI model, it splits the book’s text into tokens or word fragments. For example, the phrase hello, my friend might be represented by the tokens he, llo, my, fri, and end. Some tokens are actual words; some are just groups of letters, spaces, and punctuation. The model stores these tokens and the contexts in which they appear in books. The resulting LLM is essentially a huge database of contexts and the tokens that are most likely to appear next.

The model can be visualized as a map. Here’s an example, with the actual most-likely tokens from Meta’s Llama-3.1-70B:

When an LLM “writes” a sentence, it walks a path through this forest of possible token sequences, making a high-probability choice at each step. Google’s description is misleading because the next-token predictions don’t come from some vague entity such as “human language” but from the particular books, articles, and other texts that the model has scanned.

By default, models will sometimes diverge from the most probable next token. This behavior is often framed by AI companies as a way of making the models more “creative,” but it also has the benefit of concealing copies of training text.

Sometimes the language map is detailed enough that it contains exact copies of whole books and articles. This past summer, a study of several LLMs found that Meta’s Llama 3.1-70B model can, like Claude, effectively reproduce the full text of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. The researchers gave the model just the book’s first few tokens, “Mr. and Mrs. D.” In Llama’s internal language map, the text most likely to follow was: “ursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.” This is precisely the book’s first sentence. Repeatedly feeding the model’s output back in, Llama continued in this vein until it produced the entire book, omitting just a few short sentences.

Using this technique, the researchers also showed that Llama had losslessly compressed large portions of other works, such as Ta-Nehisi Coates’s famous Atlantic essay “The Case for Reparations.” By prompting with the essay’s first sentence, more than 10,000 words, or two-thirds of the essay, came out of the model verbatim. Large extractions also appear to be possible from Llama 3.1-70B for George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and others.

The Stanford and Yale researchers also showed this week that a model’s output can paraphrase a book rather than duplicate it exactly. For example, where A Game of Thrones reads “Jon glimpsed a pale shape moving through the trees,” the researchers found that GPT-4.1 produced “Something moved, just at the edge of sight—a pale shape, slipping between the trunks.” As in the Stable Diffusion example above, the model’s output is extremely similar to a specific original work.

This isn’t the only research to demonstrate the casual plagiarism of AI models. “On average, 8–15% of the text generated by LLMs” also exists on the web, in exactly that same form, according to one study. Chatbots are routinely breaching the ethical standards that humans are normally held to.

Memorization could have legal consequences in at least two ways. For one, if memorization is unavoidable, then AI developers will have to somehow prevent users from accessing memorized content, as law scholars have written. Indeed, at least one court has already required this. But existing techniques are easy to circumvent. For example, 404 Media has reported that OpenAI’s Sora 2 would not comply with a request to generate video of a popular video game called Animal Crossing but would generate a video if the game’s title was given as “‘crossing aminal’ 2017.” If companies can’t guarantee that their models will never infringe on a writer’s or artist’s copyright, a court could require them to take the product off the market.

A second reason that AI companies could be liable for copyright infringement is that a model itself could be considered an illegal copy. Mark Lemley, a Stanford law professor who has represented Stability AI and Meta in such lawsuits, told me he isn’t sure whether it’s accurate to say that a model “contains” a copy of a book, or whether “we have a set of instructions that allows us to create a copy on the fly in response to a request.” Even the latter is potentially problematic, but if judges decide that the former is true, then plaintiffs could seek the destruction of infringing copies. Which means that, in addition to fines, AI companies could in some cases face the possibility of being legally compelled to retrain their models from scratch, with properly licensed material.

In a lawsuit, The New York Times alleged that OpenAI’s GPT-4 could reproduce dozens of Times articles nearly verbatim. OpenAI (which has a corporate partnership with The Atlantic) responded by arguing that the Times used “deceptive prompts” that violated the company’s terms of service and prompted the model with sections from each of those articles. “Normal people do not use OpenAI’s products in this way,” the company wrote, and even claimed “that the Times paid someone to hack OpenAI’s products.” The company has also called this type of reproduction “a rare bug that we are working to drive to zero.”

But the emerging research is making clear that the ability to plagiarize is inherent to GPT-4 and all other major LLMs. None of the researchers I spoke with thought that the underlying phenomenon, memorization, is unusual or could be eradicated.

In copyright lawsuits, the learning metaphor lets companies make misleading comparisons between chatbots and humans. At least one judge has repeated these comparisons, likening an AI company’s theft and scanning of books to “training schoolchildren to write well.” There have also been two lawsuits in which judges ruled that training an LLM on copyrighted books was fair use, but both rulings were flawed in their handling of memorization: One judge cited expert testimony that showed that Llama could reproduce no more than 50 tokens from the plaintiffs’ books, though research has since been published that proves otherwise. The other judge acknowledged that Claude had memorized significant portions of books but said that the plaintiffs had failed to allege that this was a problem.

Research on how AI models reuse their training content is still primitive, partly because AI companies are motivated to keep it that way. Several of the researchers I spoke with while reporting this article told me about memorization research that has been censored and impeded by company lawyers. None of them would talk about these instances on the record, fearing retaliation from companies.

Meanwhile, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has defended the technology’s “right to learn” from books and articles, “like a human can.” This deceptive, feel-good idea prevents the public discussion we need to have about how AI companies are using the creative and intellectual works upon which they are utterly dependent.

The post AI’s Memorization Crisis appeared first on The Atlantic.