The composer Matthias Pintscher was hiking in the Black Forest a few years ago, considering an offer to compose a new work for the Berlin State Opera, when the words to a German fairy tale came rushing back to him.

When he was 5, Pintscher had listened obsessively to a story called “The Cold Heart” (“Das kalte Herz”) on cassette. The tale is about a poor charcoal burner who trades his heart for a slab of stone. The haunting story seemed like the ideal subject for a new opera — Pintscher’s first in over 20 years. That piece, also titled “Das kalte Herz,” premieres in Berlin on Sunday, then travels to the Opéra-Comique in Paris on March 11.

Pintscher, now 54, is the music director of the Kansas City Symphony, a frequent guest conductor with the world’s leading orchestras and a composer of darkly mysterious and precisely imagined music. Born in Marl, Germany, he now lives in New York City and teaches composition at the Juilliard School.

In an interview, Pintscher said he saw “Das kalte Herz” as a breakthrough work that shows the confidence to let the audience reach its own conclusions. In the kind of art he wants to make, Pintscher added, “there’s always that element that something feels not completed by the artist, but it’s passed over to the viewer, to the reader, to the listener.”

“You complete the sensations,” he added, “because you feel.”

For that to happen, Pintscher and his librettist, Daniel Arkadij Gerzenberg, had to adjust their source material. In the original fairy tale, written by Wilhelm Hauff in the early 19th century, Peter, the charcoal burner, longs to be wealthy and enters into a Faustian bargain with an evil forest spirit. After exchanging his heart for a piece of marble, he becomes a brutal miser, whipping his wife to death for giving a poor man some of his wine. The moral is that a person should accept his lot in life, no matter how lowly.

Gerzenberg, a poet and pianist, replaced the tale’s tidy narrative about the risks of greed with a series of dreamlike tableaux. Drawing on troubling experiences from his own past, he emphasized the central character’s helplessness in the face of pressure from others.

Gerzenberg has said that he was groomed and sexually abused by a trusted authority figure and lover of culture as a teenager. That violation, which he described in a recent memoir, shaped his approach to the opera’s libretto. In Gerzenberg’s telling, the character of Peter is traumatized — though the reason is never made explicit — and therefore willing to give up his heart.

“The opera is definitely about methods of manipulation,” Gerzenberg said, “and how people can be influenced to do things that they maybe don’t want to do.”

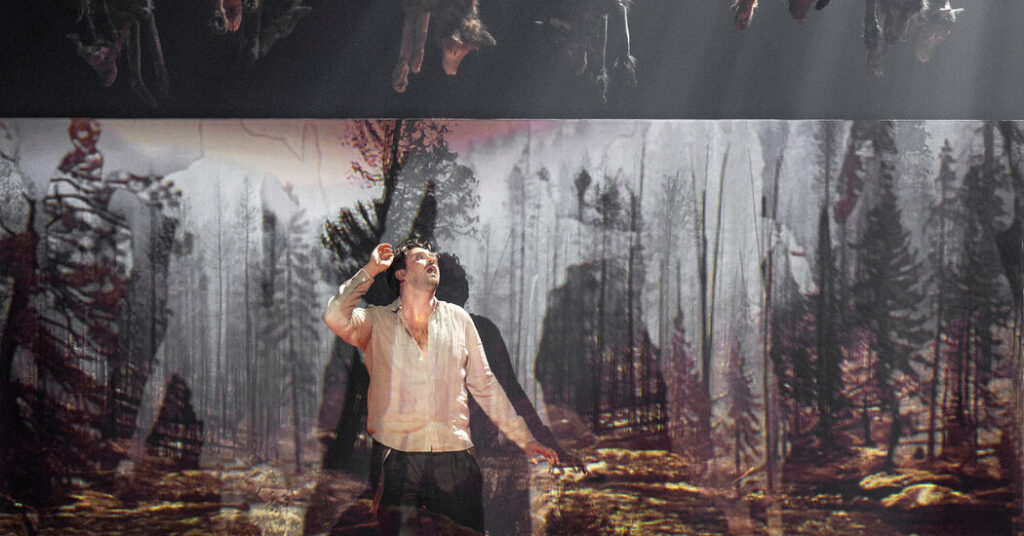

Pintscher’s score is full of sounds that are hard to identify. In a dark forest, a crunch can be a predator, an evil spirit or your own footsteps on a leaf. In “Das kalte Herz,” Pintscher has percussionists rub plastic cups against an instrument called a thunder sheet. The resulting sound can recall a howling wind or a human cry.

In this noisy texture, traditional operatic singing creates a stark contrast between the human characters and the natural environment around them. This animating tension hardly lets up. The music feels “like waves gathering that never crash,” said James Darrah Black, who is directing the production.

An atmosphere of anxiety is common in Pintscher’s compositions. In “Musik aus Thomas Chatterton” for baritone and orchestra, passages of stillness are followed by terrifyingly unpredictable outbursts. In “Bereshit” for large ensemble, the instruments skitter fearfully around dark central harmonies. And in “Mar’eh” for violin and ensemble, the accompaniment adds dissonant layers to the soloist’s melodies.

For “Das kalte Herz,” Pintscher said, he took a more direct approach. His last opera, “L’Espace Dernier,” which premiered in 2004, was fragmentary and highly detailed, with a complicated interplay between light, video, poetry and instruments distributed around the auditorium. The new work, he said, is about “painting with a bigger brush on a really large canvas” so that “the singing and the complexity of the story can actually be easier to comprehend.”

What those elements add up to, though, remains an open question. In a discussion during a recent rehearsal at the Berlin State Opera, Yury Ilinov, a pianist at the company, asked Gerzenberg if he had been thinking about Russia’s war in Ukraine when he wrote the libretto. In the opera, Peter’s mother encourages the ritual removal of his heart, which reminded Ilinov of the Russian mothers who allowed their sons to fight on the front, he said.

Gerzenberg said that he had written the text before Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, but he was nonetheless pleased with the interpretation. The work’s ambiguity “allows the possibility for you to connect it with your own feelings and associations,” Gerzenberg said.

The result is a work poised between a warning and a nightmare.

“I found a way to not finish a composition off with trying to make a statement,” Pintscher said, “but to leave it open.”

The post A Fairy Tale Opera Trades the Moral for the Mysterious appeared first on New York Times.