You’re reading The Checkup With Dr. Wen, a newsletter on how to navigate medical and public health challenges. Click here to get the full newsletter in your inbox, including answers to reader questions and a summary of new scientific research.

“The only thing that relieves the pain is cannabis.” That message came from Jeffrey from Virginia, who is still experiencing debilitating pain from a car accident about 10 years ago. Like many others, he took issue with my recent column on a study showing the current evidence does not support cannabis as a treatment for most medical uses. Sandy from Massachusetts similarly reached out to say that the drug has been a “lifesaver” in addressing her fibromyalgia.

I spoke with Michael Hsu, a psychiatrist at the University of California at Los Angeles and the lead author of a JAMA paper on cannabis’s benefits and harms, to better understand how he reconciles his research with these patient anecdotes.

“There is a gap between what science can confidently tell us and what patients are experiencing in their day-to-day lives,” he told me. That gap doesn’t mean that patients are wrong or that the data are flawed; rather, clinicians need to listen carefully to patient experiences while also being transparent about what the research shows.

Hsu cautions that while cannabis may provide symptom relief for some conditions, it could be temporary if the underlying cause is not addressed. For instance, someone with back pain may be using cannabis instead of pursuing physical therapy. Or someone may be self-medicating for depression while forgoing antidepressants and behavioral therapy. “In certain cases, it can even worsen symptoms or make it harder for patients to fully engage in treatments,” he said.

How doctors advise patients on cannabis should depend on their age and medical situation. Multiple readers shared accounts in which they or their loved ones with terminal cancer found pain relief or mood improvement from cannabis products. The risk-benefit analysis for people receiving palliative and end-of-life care is very different from, say, that of a college student with insomnia or a pregnant woman with anxiety.

I also heard from many readers who claim that they have used cannabis for decades and never experienced negative effects. Joe from Maryland dismissed cannabis use disorder as a “made-up disease.”

“Honestly, I don’t know a single person who’s addicted to weed,” he wrote. “I probably know 200 people who smoke or take edibles every day.”

Kevin P. Hill, an addiction psychiatrist and associate professor at Harvard Medical School, told me that patients often don’t have insight into whether their cannabis use is problematic. “It’s very rare that someone’s going to call me up and say, ‘hey doc, I’m worried that my cannabis use is out of control,’” he said.

More often, it’s a spouse or employer pushing them to seek treatment. When patients do start talking with a clinician, they may describe repeated failed attempts to cut back or quit. They notice that their anxiety spikes without the drug or that they can’t sleep and develop strong cravings. Some realize they are showing up late or calling out sick because they feel they need to use cannabis. Others say they are missing school pickups, zoning out during family time or structuring their day around when they can get high.

Though there are no approved medications for cannabis use disorder, a range of treatments can help, including cognitive behavioral therapy and some off-label medications. The situation becomes more complicated when people use cannabis because they believe it relieves specific symptoms. In those cases, Hsu works with patients to clarify their goals, which are not necessarily for quitting outright but to feel better and function more reliably in their daily lives.

“I try to come alongside and work with them in that goal,” he said. This often means tapering from high-potency cannabis to lower-dose products and managing withdrawal symptoms as they arise. Eventually, many patients are able to stop altogether, replacing cannabis with treatments that more directly address the underlying condition they were trying to manage in the first place.

Some patients will not want to stop using cannabis altogether. In those cases, physicians I spoke with recommend a harm reduction approach that focuses on lowering risks. That can mean avoiding cannabis in combination with alcohol or benzodiazepines, which can dangerously increase sedation, and being mindful of interactions with other medications. Switching to lower-potency products also helps here, since side effects and risks tend to rise with dose. And just as with alcohol, cannabis and driving should never mix.

“We’re not trying to tell people that they can’t do what they want to do, but we don’t want them to do things that are hurting other people,” Hill said.

Both physicians also stressed the need for more clinician education. In one study, only about a third of clinicians said they felt confident talking with patients about medical cannabis, and 86 percent wanted more training. Given that about 1 in 4 Americans have used cannabis, it’s essential that clinicians can have these conversations openly and knowledgeably. As Hsu put it, “The more uncomfortable we are as a clinical field, the more patients might turn to other sources of information.”

“You’re saying the evidence isn’t conclusive, but can we agree that cannabis could still turn out to be helpful in some cases?” wrote Owen from D.C. “Would rescheduling make that easier to figure out?”

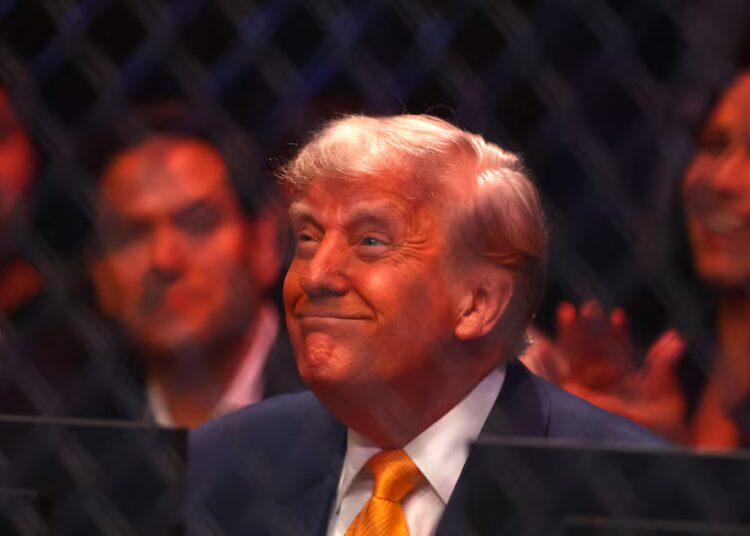

I agree with you, Owen. We need more and better cannabis science. It’s entirely possible that specific cannabinoids, which are compounds isolated from the cannabis plant, could prove effective for chronic pain or other conditions. The Trump administration’s recent decision to reschedule cannabis from the most restrictive legal category could make rigorous research easier, though the question of who will fund these studies remains. If companies are already profiting by marketing cannabis as a cure-all, they may have little motivation to invest in large randomized-controlled trials that could narrow its uses.

My other concern is that as medical care becomes more expensive and harder to access — while cannabis becomes increasingly normalized — people will turn to the drug instead of evidence-based treatment. Choosing cannabis with a clear understanding of its risks may be an individual choice, but confusing availability and popularity with proof of benefit is a public health failure.

The post What we know and don’t know about medical cannabis use appeared first on Washington Post.