The U.S. trade deficit in goods and services shrank to $29.4 billion in October, down from $48.1 billion the prior month as the Trump administration’s tariffs reshaped global trade, data from the Commerce Department showed on Thursday.

The figure was the lowest monthly trade deficit recorded since June 2009. U.S. imports have fallen while exports have remained strong, decreasing the trade deficit and seemingly accomplishing a major goal for President Trump.

But economists cautioned that some of the trend resulted from temporary fluctuations in trade in certain products, like gold and pharmaceuticals. Because of a surge in imports earlier this year, the overall trade deficit from January to October was still up 7.7 percent from the previous year.

Imports in October fell 3.2 percent to $331.4 billion from the previous month, while exports rose 2.6 percent to $302 billion. Because exports grew more than imports, the U.S. trade deficit narrowed.

Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, said that there was a lot of noise in the data for the month, and that gold and silver markets in particular had been “bonkers.”

Another force narrowing the trade deficit in the month was a collapse in pharmaceutical imports, he said. Drug companies stockpiled pharmaceuticals ahead of tariffs going into effect on the sector on Oct. 1, though many firms were ultimately spared from tariffs.

“Cutting through the noise and getting to the underlying signal in the data, it suggests to me that the deficit is as large as its ever been,” Mr. Zandi said.

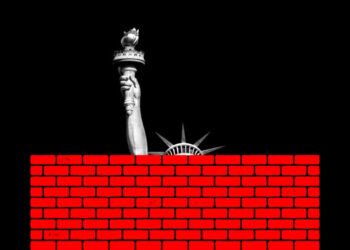

Trade flows have fluctuated wildly this year because of Mr. Trump’s tariffs. The president announced sweeping global tariffs in April, before pausing them for several months to carry out trade negotiations. Those tariffs went back into effect on Aug. 7.

On Aug. 29, the Trump administration also ended the “de minimis” exemption, which allowed foreign shipments valued at less than $800 to come into the United States tariff-free.

The administration has also imposed a variety of tariffs on products and sectors it deemed important to national security, including steel, copper and upholstered furniture. As of November, the U.S. effective tariff rate had climbed to more than 16 percent, the highest level since 1935, according to the Budget Lab at Yale, making it significantly more expensive for importers to bring goods into the country.

The Trump administration has pointed to the lower monthly trade deficits in recent months as evidence that its trade policies were working. Mr. Trump has long seen the trade deficit as a sign of an ailing American economy. He and his supporters argue that tariffs will narrow it, by boosting U.S. factory production and reducing imports.

But economists argue that bigger economic forces typically determine the size of the trade deficit, like savings rates and government spending. They have also cautioned against drawing too many conclusions from a few months of data in a particularly volatile year.

Companies imported large amounts of inventory earlier this year before tariffs went into effect, then subsequently reduced their purchases. The question for economists now is whether trade will return to more normal levels as company stockpiles go down, or if tariffs will continue to depress imports and decrease the trade deficit.

For the year through October, exports are up 6.3 percent annually, while imports have risen 6.6 percent, according to the data, which is compiled by the Census Bureau.

Tariffs could undergo more changes in the weeks to come. The Supreme Court is set to rule soon on the legality of many of the tariffs that Mr. Trump issued using a 1970s emergency law. But Trump officials have said that if those tariffs were struck down, they would use other authorities to impose new duties.

Diane Swonk, an economist at KPMG, described the monthly drop in the trade deficit as “stunning,” but said that it was largely driven by trade in gold. Investors have been buying and selling gold in part to offset uncertainty related to the tariffs this year. Gold made up nearly 90 percent of the rise in exports in October and about 13 percent of the decline in imports, she said.

Americans imported slightly more passenger cars, cellphones, toys and appliances in the month. And imports of high-tech goods remained strong because of tariff waivers for the electronics sector and the building of American data centers to feed A.I. demand, Ms. Swonk said.

The U.S. trade deficit with China continued to shrink in October, while trade deficits with Mexico, Thailand and Taiwan all hit record highs, in part reflecting A.I.-related imports.

Beyond gold and precious metals, exports of other products looked relatively weak. Shipments abroad of American aircraft, computers, soybeans and pharmaceutical goods all fell on a monthly basis in October. Soybean exports were down $3.3 billion in the year through October, as China curtailed its purchases of U.S. beans and bought from South America instead.

Ana Swanson covers trade and international economics for The Times and is based in Washington. She has been a journalist for more than a decade.

The post U.S. Trade Deficit Fell to Lowest Level Since 2009 as Tariffs Reshape Trade appeared first on New York Times.