Plenty of presidents have reached for a salty four-letter word when the moment felt right, but why would the Trump administration stop there? This week it’s been getting significant mileage from a salty four-letter acronym that comprises a separate salty four-letter word. It’s like the opposite of gilding the lily.

The acronym in question is FAFO, and remarkably, it’s being offered as the justification for the U.S. invasion of Venezuela. First the president’s people were talking about the Monroe Doctrine, which then morphed into the Donroe Doctrine. But soon enough it was FAFO.

For those unfamiliar with the acronym, the first letter stands for a certain curse word, followed by “around and find out.” It amounts to something like “Don’t mess with me or you’ll regret it.” The implication, in this context, is that Nicolás Maduro unwisely did the former and now must do the latter.

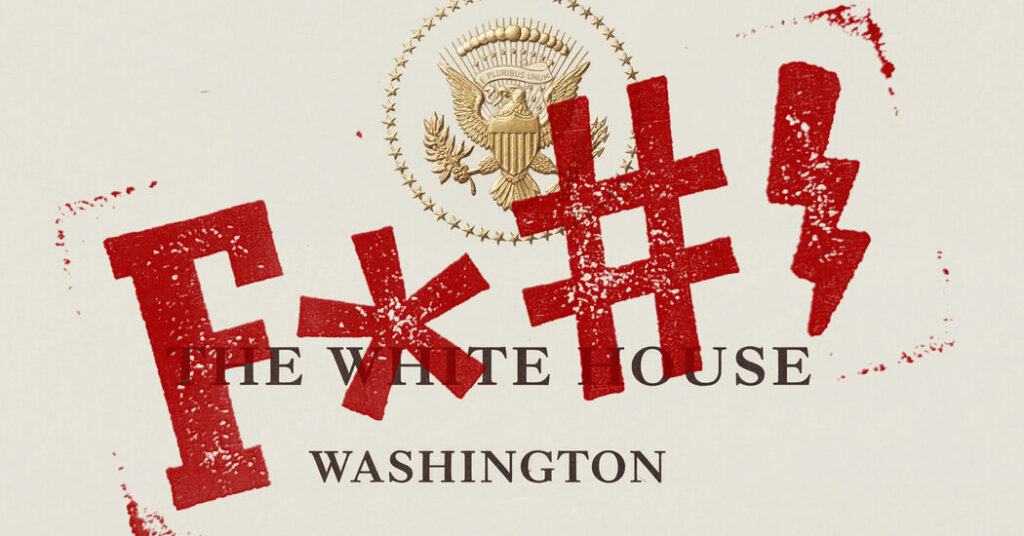

At the news conference, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth told the nation that Maduro “effed around and he found out.” Later, the White House posted an image on social media of Trump striding up a flight of steps determinedly. Toward the bottom of the image were the large letters “FAFO” and the White House logo. My bet is that we will hear a lot about the FAFO doctrine this year. By December, it will be a contender for a spot on my list of the most important words of 2026.

Superficially, it may seem jarring that people entrusted to run our nation, suit-wearing people who take themselves very seriously, would throw around a term like this. But I actually think it’s a positive development. The normalization of that word — the one Hegseth abbreviated as “eff” — is a sign of maturity in American English.

Like it or hate it, the word serves a very useful purpose.

In Middle English, it was ordinary, not profane. It found its way into last names, and was casually entered into court records. It was used publicly in names of locales of ill repute. (By the way, for those who wish to dive deeper into the word’s history, I recommend Jesse Sheidlower’s lovely, honest and appealingly obsessive book “The F-Word.”)

It was only in the 1500s that people started cordoning off the F-word as “dirty” and opting for Latinate substitutes in polite company. The reason for the change may have had something to do with the Protestant Reformation. That movement brought with it a new focus on the individual’s relationship to God — and the sense that the human body was shameful, even revolting, and only the soul was pure. Whereas once only religious words like “damn” and “hell” seemed shocking, now mundane names for bodily parts and processes sounded unclean, even naughty. So over time, polite people sought out alternatives, which is how we arrived in the modern era having to choose between formal words such as “copulate,” borrowed from Latin (and never given back), and euphemisms such as “sleep with” or “make love.”

This dichotomy between formal and dirty names for intimacies of the body, with nothing vanilla in between, is in the end a kind of prudery incommensurate with how a great many of us live, think, feel and speak. So I’m delighted to see a general loosening of the boundaries. A recent report I read about paleoanthropology made reference to the spot on some fossilized remains, where the animal’s “butt muscle” would have attached. Why not? “Gluteal musculature” sounds like an anatomy textbook and the term that rhymes with “class” is, well, low class. This approach is more honest, less prim, than assorted euphemisms like “rear end,” “derrière,” and “bottom.”

As for the F-word, Joe Biden used it at the signing of the Obamacare bill. A hit pop song had it in its title in 2010. The acronym WTF is everywhere.

In 1934, the lexicographer Allen Walker Read called the F-word “the word that has the deepest stigma of any in language.” Today, that distinction belongs not to a bodily term but to a racial one — the N-word — with all the other racial slurs tied for second place. Surely this stigma reflects a more sophisticated approach to linguistic sensitivity, as it works to resist tribal hatreds rather than to deny our own physical realities.

Don’t get me wrong — I think the Trump administration’s particular use of FAFO is revoltingly jocular for an event that reportedly killed at least 80 people and may have violated international law. But I’m still happy to see us getting over antimacassar notions about the body, and getting to the point where we can all speak the way we think and live.

The post The Trump Administration’s Coarseness Is a Sign That English Has Grown Up appeared first on New York Times.