Ron Protas, a confidant of the great modern dancer and choreographer Martha Graham, who named him her sole heir and bequeathed him the ownership of her dances, setting off a grueling legal battle over her legacy with the troupe she had founded, died on Oct. 15 at his home in Manhattan. He was 84.

Kenneth Topping, a friend and former Graham company dancer and administrator, confirmed the death, which was not widely reported at the time. He said the cause was cardiovascular disease.

Graham, one of the 20th century’s most influential cultural figures, died in 1991 at 96. Tensions between her company and Mr. Protas then simmered for a decade before boiling over in a court fight starting in 2001, after which performances by her dancers all but ended for two years.

To Mr. Protas’s critics in the Graham organization, who accused him of profiteering from her legacy, he was “the most reviled man in dance,” The New York Times reported in 2000.

Mr. Protas countered that members of the Graham company were jealous that Graham, whose pathbreaking early works had brought modernism to dance, had chosen him as her heir, even though he had no formal dance training, as he readily conceded, beyond learning the merengue at a Fred Astaire studio.

When he befriended Graham in the late 1960s, Mr. Protas was a freelance photographer; he was in his late 20s, and she was 47 years his senior. She had stopped performing and suffered alcohol-induced bouts of depression and ill health, which in 1971 landed her in Doctors Hospital on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

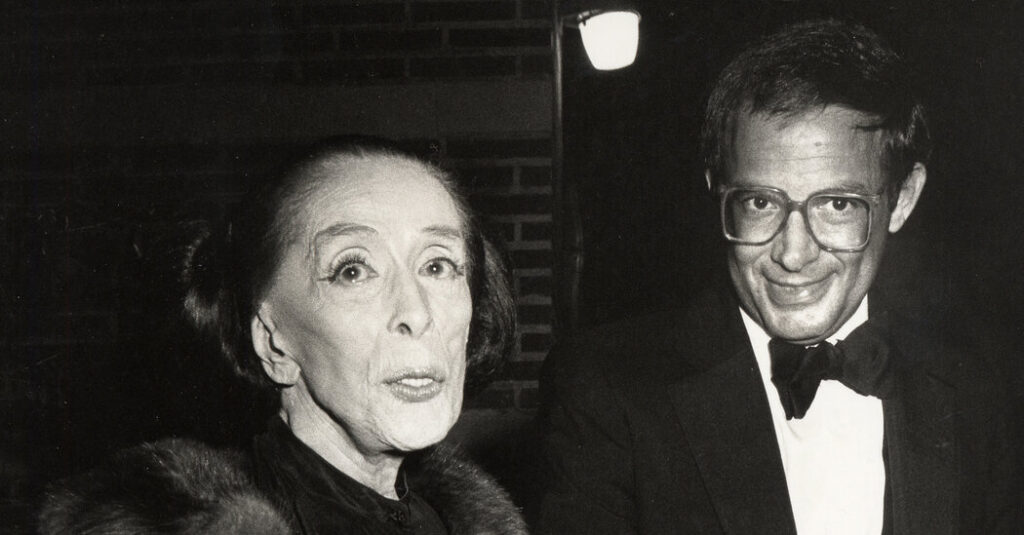

Mr. Protas attended her faithfully as she returned to a productive career. Over the nearly two decades that followed, he was constantly at her side: holding a microphone when she spoke in rehearsals, in the wings at performances as she dictated corrections to dancers that he jotted down on legal pads, escorting her in black tie to gala fund-raisers.

He became the dominant personal and professional figure in Graham’s life as she pushed away longtime favorite dancers and company administrators.

In her 1991 autobiography, “Blood Memory,” she called Mr. Protas the person “to whom I have entrusted the future of my company.” Her will left him all her property, including sets, costumes and the rights to the more than 180 dances that she had created since founding her company in 1926.

After her death, Mr. Protas became artistic director of the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, which maintained her legacy through a school and performing company in Manhattan. Despite his lack of experience in dance or arts administration, he took on key decisions about programming and casting, and critiqued dancers during rehearsals.

“He spoke like Martha and directed people, or tried to,” Mr. Topping, a company dancer from 1984 to 2004, said in an interview.

But dancers bristled at his presuming to tell them how to perform. After a rocky decade, the strife between Mr. Protas and company members reached a breaking point in 2000, when the trustees of the Graham Center removed him as artistic director.

He responded by suing to stop the center from using Graham’s name, which he had trademarked, and from performing her dances or teaching her style of intense, angular movements, known as the Graham technique.

He told The Times that the disputes were fueled by personal rivalries sparked when Graham anointed him her heir.

“Her act of choosing me created jealousy and animosity because all the other dancers felt that they should have been chosen by her, and that is a big part of it,” he said.

Mr. Protas ultimately lost the case. A federal judge, in decisions in 2002 and 2005, awarded control of almost all of Graham’s dances to the Graham Center. The judge, Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum, ruled that the dances had not been Graham’s to pass on in her will; her early works had already been given to her company, and those created after 1956, when she legally became an employee of it, were “works for hire.”

Judge Cedarbaum also said that Mr. Protas owed the center $241,000 in damages.

Ronald Allen Protas was born on Sept. 2, 1941, in New York City and raised in Brooklyn, the younger of two sons of Irving and Ruth Protas. His father owned a luggage business, and his mother had a passion for the theater.

He graduated from Erasmus High School in Brooklyn and New York University. He attended Columbia Law School but left before finishing.

He met Graham around 1969, the year she stopped performing. “I had lost my will to live,” she wrote of that period in her autobiography. “I stayed home alone, ate very little and drank too much and brooded.”

She was hospitalized with diverticulitis — or, as some friends suspected, because of her alcohol consumption. Mr. Protas was among her visitors, and one day, when she was out of breath and no nurse had answered her call, he dropped the flowers he had brought and rushed her an oxygen tank and mask.

He visited repeatedly, and she came to believe that he was the one who had supported her at her lowest moment. In dedicating “Blood Memory” to him, among a list of others, she wrote that Mr. Protas “shared a new direction and animation for my life.”

“Ron has been with me for 25 years,” she wrote, “and I have trained him in my technique. He knows deeply the roles I have created and can intuit what I want.”

A different portrait of Mr. Protas emerged from “Martha,” a 1992 biography of Graham by Agnes de Mille, the renowned dancer and choreographer, who knew Graham intimately.

De Mille described Mr. Protas as a hanger-on whom Graham at first considered a nuisance, but who insinuated himself into her life, albeit with her consent.

“He held a microphone to her lips at every rehearsal,” de Mille wrote, “he supported her as she walked, he brought her tea and comforts, he tucked her in at night and turned on the electric blanket, and he took care that she never had an interview or a conversation that he did not monitor. So Martha could not be reached except with his permission.”

According to de Mille, Mr. Protas deliberately sidelined others who had influence with Graham, taking on the roles of de facto business manager and artistic adviser.

“One by one, Martha and Ron rid themselves of all the faithful workers and the board members — relentlessly, brutally and finally,” she wrote. “It was almost Russian in its thoroughness.”

Mr. Protas left no immediate survivors.

He pursued appeals of his lawsuit against the Graham company through 2006. After severing ties with the company, he supported himself by selling Graham’s personal property that he had inherited, including jewelry, costumes and art works, which filled his cramped apartment on Manhattan’s East Side.

Mr. Topping, who was also director of the Graham ensemble and school before leaving the company in 2004, said he reconnected with Mr. Protas a few years ago and began visiting him regularly. By then, most of the inherited valuables had been sold, and Mr. Protas owed tens of thousands of dollars in back rent.

The courts had left Mr. Protas the owner of two Graham dances. He hoped to raise money by leasing one, “Seraphic Dialogue,” and talks were held with the Graham company.

But a deal fell through because Mr. Protas could not bring himself to confer something of value on his old nemesis.

“He was living in the past,” Mr. Topping said, “and living with the constant hope of vengeance.”

Trip Gabriel is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk.

The post Ron Protas, Polarizing Keeper of Martha Graham’s Legacy, Dies at 84 appeared first on New York Times.