As the rising cost of basic expenses continues to fuel an affordability crisis, millions of workers will see an increase in pay this month with new minimum wages taking effect.

Nineteen states, as well as 49 cities and counties, are increasing their wage floors to at least $15 per hour for some or all employees after wage hike campaigns across the country in recent years. In total, 88 states, counties and cities will make the adjustment by the end of the year, according to a report by the National Employment Law Project, which supports workers’ rights.

For the first time, more Americans will earn a minimum wage of $15 or more than will earn the federal minimum of $7.25, according to the Economic Policy Institute. The federal rate has remained unchanged since 2009, despite broad public support for an increase.

Supporters of increasing the minimum wage argue that it should actually be a “living wage” that ensures workers can cover their basic expenses. Critics have long argued that such increases hurt small businesses, kill jobs or cut worker hours and raise consumer prices.

The modest raises come as low-paid hourly workers struggle to cover bare necessities.

“No minimum wage is truly a living wage, but any increase in the wage floor is good for workers,” said Yannet Lathrop, a senior researcher and policy analyst at the National Employment Law Project. “It will mitigate the pain a little more.”

The increases, a majority of which took effect Jan. 1, will boost the earnings of about 8.3 million workers by a total of $5 billion, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Colorado’s minimum wage increased to $15.16 per hour from $14.81, while Maine’s rose to $15.10 from $14.65. In Minneapolis, the minimum climbed to $16.37 from $15.97, and in Tucson, to $15.45 from $15. Some tipped wages will also increase.

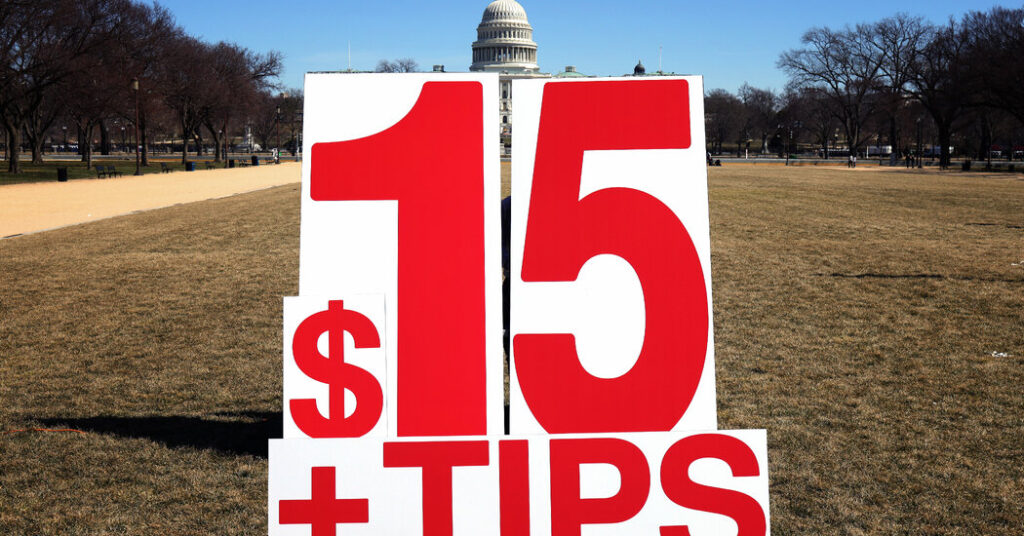

Many of the raises were a result of grass roots campaigns waged at the state and local levels across the country, some of which grew out of the “Fight for $15” movement that began in 2012 with fast food worker strikes in New York. At the time, paying workers $15 per hour was considered a fringe idea, but the campaign, conducted against a backdrop of rising costs and stubborn income inequality, gained traction and changed labor rights demands.

In Missouri, workers at airports, fast food restaurants, farms and warehouses organized for more than a decade to increase the minimum wage.

In 2024, Proposition A, a minimum wage ballot measure, passed with nearly 60 percent of voter support. Last week, the minimum wage jumped to $15 an hour from $13.75, increasing pay for nearly 500,000 workers, according to Missouri Jobs With Justice, an advocacy organization. Additional increases beyond 2026 were to be calculated by the Consumer Price Index. But last year, Gov. Mike Kehoe, a Republican, signed into law a bill that limited the minimum wage increase.

Alejandro Gallardo, 32, a prep cook at a restaurant in Columbia, Mo., is now earning $15 an hour — allowing him to earn about $200 more per month, before taxes. He was among the workers who gathered signatures and spoke to voters to drum up support for Proposition A.

“I would say I make enough to survive, but there is not a lot of room for luxuries or splurging,” Mr. Gallardo said. “The raise will help. It’s nice to see the numbers go up a bit for bills like groceries.”

In Nebraska, where many jobs are tied to the agriculture industry, workers and job rights advocates knocked on doors in all 93 counties beginning in 2021.

They went to church potlucks, gas stations, breweries, post offices and courthouses, pitching the idea that $15 an hour was necessary to afford the cost of living.

About 60 percent of Nebraska voters approved a proposal in 2022 to incrementally raise the minimum wage to $15 from $9, beginning in 2023. At the time, about 150,000 workers in the state were impacted. This month, the wage floor there increased to $15 from $13.50; future increases will be tied to the cost of living.

“The state is known as having a relatively low cost of living and low unemployment rate, but that is not the economic reality many Nebraskans face,” said Ken Smith, the director of the economic justice program at Nebraska Appleseed, an advocacy group. “Nearly half of our work force is made up of low-wage workers who are experiencing the economic pressure of affordable housing, grocery and health care costs.”

Audra D. S. Burch is a national reporter, based in South Florida and Atlanta, writing about race and identity around the country.

The post Minimum Wage Rises in Some States as Workers Struggle with Basic Costs appeared first on New York Times.