In “Magellan,” Lav Diaz’s haunted dream of a movie about Ferdinand Magellan’s effort to circumnavigate the world, the Portuguese explorer’s famed exploits are charted selectively. Played with pungent severity by Gael García Bernal, this Ferdinand is at once opaque and obvious, a man of his time, a harbinger of the future, and an instrument of terror. He’s a husband and a father, too, though Diaz is less interested in his personal affairs than in the meaning of notions like discovery and what it portends when one group of people violently imposes itself on another, which also makes this a story of imperialism.

The world became much smaller when a single lonely ship from the Magellan expedition finished its trip around the globe after three harrowingly difficult years. By the time that ship, the Victoria, returned to Spain in 1522, the expedition had lost several vessels while crossing oceans, snaking through a perilous strait and sailing tens of thousands of miles. Most of the crew was dead, and so was Magellan, who, at 41, was killed by Indigenous people. Demanding that they cede to his interests, he led a small group to attack them. The population responded in kind, ending his adventures. A year and a half later, the surviving crew finished the trip.

Corpses are scattered across the ground when Ferdinand, badly wounded and wearing a metal breastplate, first appears onscreen. It’s 1511 in the aftermath of the successful Portuguese campaign to seize the Malaysian port city of Malacca. Although Diaz inserts times and place names throughout the movie, which function as helpful narrative coordinates, his storytelling is more elliptical than encyclopedic. He skims over historic events and omits crucial travelers, and characters at times enter and exit without much introduction. They also don’t deliver the simple, convenient lessons and summations that are familiar from more conventional movies; it’s gratifying not being pandered to.

Here, history and story tend to convene in crystallizing moments, in faces, gestures, actions and in blunt, cruel words. The most arresting way that Diaz telegraphs, though, is through the sheer beauty of his images. The movie is often visually intoxicating, at moments gasp-out-loud ravishing, especially in its presentation of the natural world, which can have a soft visual quality that deepens the sense of otherworldliness. The square framing tightly focuses your gaze, as do the minimal camera movements. When the camera does move, the effect can be startling, as in an early, leisurely push into a lush, verdant inlet that suggests what this ostensible new world may have looked like from the deck of a ship.

At other times, Diaz’s use of tableau-vivant-style compositions and chiaroscuro evokes some Renaissance paintings, reminders of the world that birthed Ferdinand. Diaz sketches in that world quickly and starkly. Soon after Ferdinand appears, there is a cut to a man clutching a bottle and staggering into a scene of carnage, like a drunk after a horrific night on the town. This is Afonso de Albuquerque (Roger Koza), the Portuguese general who led the assault on Malacca. After taking a swig, he addresses Ferdinand and other soldiers, and stakes Portugal’s claim. “Medina and Mecca,” he says, “will become remote deserts, and Islam will finally disappear.” Then he passes out and falls into the dirt, the soldiers roaring with laughter.

There’s absurd comedy in this spectacle: So much for the glories of the Age of Discovery! You could almost laugh along with Ferdinand and the others if the whole thing — the ravaged dead, the triumphant living and the specter of the colonialist future — weren’t so grim. Diaz, though, doesn’t encourage either your pity or outrage. Instead, for the most part, he retains a measured, quasi-analytic distance. Diaz’s unheroic, non-psychological conception of the explorer as well as Bernal’s hard, heavy presence and forcefully uningratiating performance also keep you at a remove. Far more expressive is Ferdinand’s enslaved servant, Enrique (Amado Arjay Babon), who becomes a very different, ethically and politically, fellow traveler.

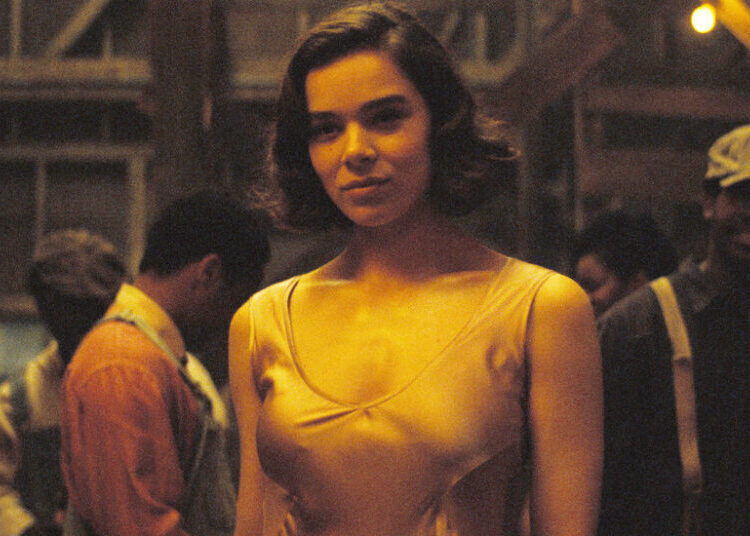

There’s plenty of drama here nevertheless, and tension, too, including when Ferdinand returns to Portugal, where he recuperates from a gangrenous wound (the rot has already set in), weds a much younger woman, Beatriz (Ângela Azevedo), and lands on a new route to the Spice Islands (a.k.a. Indonesia) for honor and riches. Some histories remember Magellan for his adventures, ambitions, tenacity and navigational prowess, as well as for his putative discovery of extant societies. Diaz instead skewers both the man and the familiar, politically expedient, aggrandizing myths. In one queasily amusing scene that distills Diaz’s point of view, the explorer and an associate discuss a possible new spice route and how they’ll sell their plans to the Portuguese king. “We work for his greed,” they chortle repeatedly.

In the end, Ferdinand goes to the Spanish king to fund the expedition, and soon leaves on his long, grinding journey. Diaz re-creates some of the ensuing onboard drama (there were mutinies), and omits some grim details. (When the food ran out, the ships’ rats went on the menu.) Instead, as he does from the start, Diaz returns repeatedly to the places and the people who Ferdinand and his crew encountered, exploited and occasionally slaughtered. The explorer has his moments of triumph, including in his campaign to convert some Native people to Christianity, an effort that helps undo him. Yet nothing expresses the sweep and scope of his adventures as powerfully as the look of horror that fills the face of an Indigenous woman who, while out one pacific day, looks up and sees the beginning of her world’s end.

Magellan Not rated. With English subtitles. Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes. In theaters.

Manohla Dargis is the chief film critic for The Times.

The post ‘Magellan’ Review: The Beauty and the Bloodshed of a Smaller World appeared first on New York Times.