Lynda Blackmon Lowery, a young foot soldier in the fight for voting rights in Selma, Ala., who was 14 when law enforcement officers savagely attacked her and many other unarmed protesters on “Bloody Sunday” in 1965, died on Dec. 24 at her home in Selma. She was 75.

Her daughter Danita Blackmon confirmed the death but did not specify a cause.

Ms. Lowery, then known as Lynda Blackmon, said she was arrested nine times before she turned 15 for participating in civil rights protests. In one of the pivotal events in the civil rights movement, she gathered with some 600 people on March 7, 1965, on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma for a planned march to Alabama’s capital, Montgomery.

From the crest of the bridge they could see white state troopers and sheriff’s deputies — some on horseback — wielding nightsticks and whips, ready to enforce the segregationist Gov. George C. Wallace’s order to halt the march.

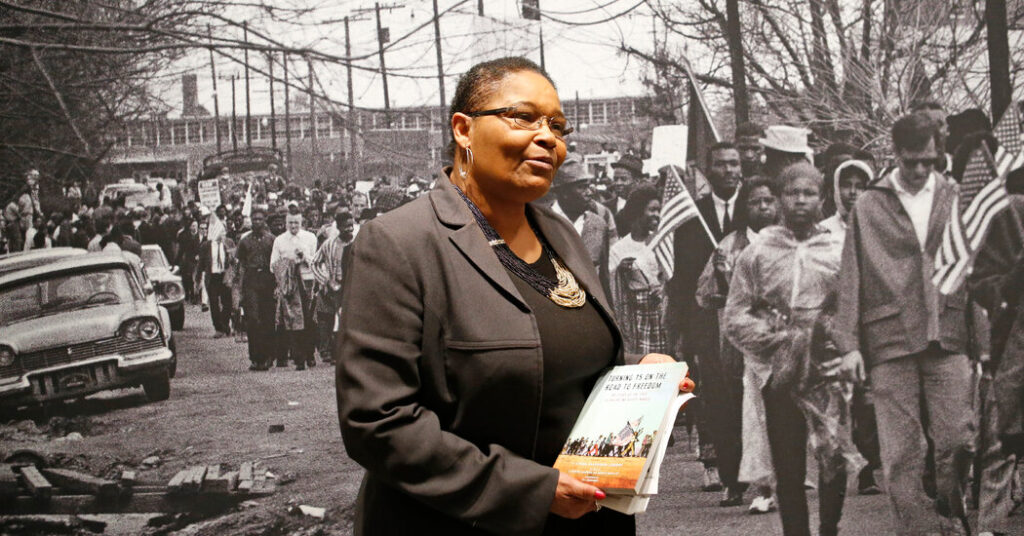

“At first I tried to tell myself it would be okay, because there were so many of us,” Ms. Lowery recalled in her 2015 book, “Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom: My Story of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March,” which she wrote with Elspeth Leacock and Susan Buckley. “Then I saw the state troopers putting on gas masks and I got really scared. I’d only seen a gas mask on TV, but somehow I knew something dangerous was happening.”

After ignoring orders to disperse, the marchers felt tear gas burning their eyes and lungs. She heard a crude racial epithet shouted at her and remembered being grabbed by a man who struck her twice with a baseball bat, leaving gashes that required seven stitches over her right eye and 28 on the back of her head. He continued to hit her as she fled.

Many others were violently attacked as well, including the civil rights leader John Lewis, one of the march’s organizers, whose skull was fractured by a trooper’s billy club.

Bloodied, she was placed on a stretcher, but she jumped off and began running. That’s when she saw her sister, JoAnne, “lying in a man’s arms,” she recalled. “I ran to him crying, ‘Oh, she’s dead. They killed my sister!’”

Told that her sister was alive but that she had fainted, she “slapped her on the side of the face,” Ms. Lowery wrote. Once her sister came to, they ran to a church for safety. They were soon driven to a hospital, and JoAnne, who was lying on her sister’s lap in the car, remembered the blood from Ms. Lowery’s wounds dripping on her face.

“I was 14 years old,” Ms. Lowery said in “American Dignity” (2025), a short documentary film directed by Hanson Hosein, in collaboration with Common Power, a voting rights organization. “I had done nothing — nobody on that bridge that day had done anything for that blatant brutality.”

Lynda Diane Blackmon was born on March 22, 1950, in Selma. Her father, Alfred Blackmon, was a cabdriver. Her mother, Ludie (Wright) Blackmon, died in childbirth at a hospital in 1957, at age 34, while waiting for blood to arrive from Birmingham.

“I heard my grandmother and the older people saying that she wouldn’t have died if she hadn’t been colored,” Ms. Lowery said in an oral history interview in 2021 with the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza in Dallas, which chronicles the history of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and considers civil rights part of his legacy.

In 1963, her maternal grandmother, who had helped care for her after her mother’s death, took Lynda to the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Selma to hear the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speak.

“In that speech, he said three words that I have lived by since the age of 13,” Ms. Lowery said in her oral history. “He said you can get anybody to do anything with ‘steady, loving confrontation.’”

At first, the words didn’t sink in. But when he repeated them, she said that she jumped up and exclaimed, “That’s how I’m going to do it!”

She joined the civil rights movement, first as a gofer (her tasks included informing parents when their children had been arrested) and later as a protester, which led to her arrests and incarceration.

When a federal judge authorized another march from Selma to Montgomery — this one to start on March 21 — she said she wanted to go. She asked her father for permission, but he agreed only when two older activists, Amelia Boynton Robinson and Marie Foster, promised to look after her, Ms. Lowery’s sister, JoAnne Bland, said in an interview.

Although thousands rallied in Selma and Montgomery, only 300 marched all the way from one city to the other — potentially dangerous territory that included a long stretch on a two-lane highway. Lynda was chosen to be one of those who completed the full 54-mile trek because “she was among the most dedicated to the movement,” Charles Mauldin, who was a 17-year-old student marshal during the march, said in an interview.

She was also one of the youngest in the group, Ms. Bland said.

On the second day of the march, Lynda turned 15. That morning, she panicked at the sight of three National Guard members, with bayonets on their rifles, believing that they were going to kill her. After being assured that they were there for protection, she calmed down.

On the final day, when the marchers reached Montgomery, she looked around for Governor Wallace outside the Capitol building. “They said he was behind the curtain peeking out, but I couldn’t tell,” she recalled in her book. “I got as close as I could and shouted, ‘I’m here, Governor Wallace, I’m here!’”

After returning to school, she continued to attend protest meetings but no longer marched or was arrested.

The inhumanity that had been inflicted on Ms. Lowery and the other Selma marchers was captured on national television, catalyzing congressional support for the Voting Rights Act, which banned racial discrimination in balloting. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the act into law on Aug. 6, 1965.

“We had won!” Ms. Lowery wrote. “My buddies and I who had gone to jail so many times had won.”

Ms. Lowery went on to work as a home health aide and safety officer before receiving a bachelor’s degree in sociology from the College of Staten Island in New York in 1982. For many years, she was a case manager at a mental health center in Selma.

In addition to her daughter Danita and Ms. Bland, Ms. Lowery is survived by another daughter, Bonita Blackmon; three grandchildren; and a great-grandson. Her husband, Collie Lowery, died in 2019.

Ms. Bland is a founder of Foot Soldiers Park, an organization dedicated to preserving Selma’s civil rights history and supporting the city’s Black community. The “foot soldiers” who marched in Selma on “Bloody Sunday” received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2016.

Like many of them, Ms. Lowery was troubled by the violence they had endured and its long aftermath. Years later, crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge could still make her tremble. About five years ago, she was “traumatized” when she looked at photographs of herself being beaten during the protest — images she had never seen before — Ms. Buckley, her co-author, said.

“I still deal with, occasionally, those memories,” Ms. Lowery said in “American Dignity.” “But they’re back far enough for me to be able to share it with somebody else so they’ll know how I feel.”

Richard Sandomir, an obituaries reporter, has been writing for The Times for more than three decades.

The post Lynda Blackmon Lowery, One of the Youngest Selma Marchers, Dies at 75 appeared first on New York Times.