In the days following the Donald Trump-ordered toppling of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, Democratic critics largely fell into two camps.

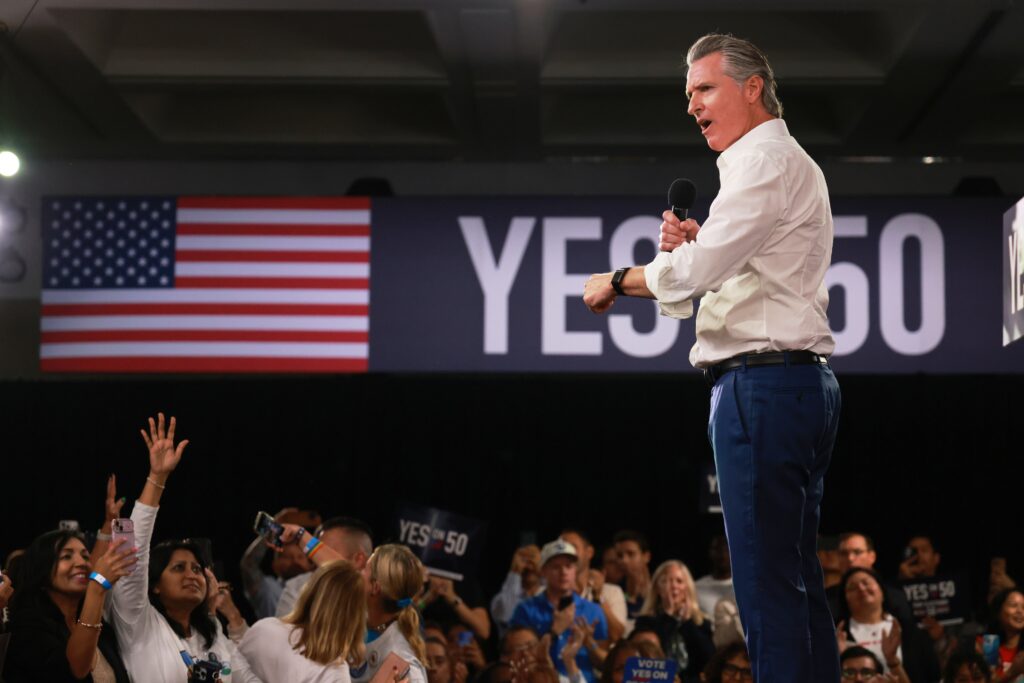

Many elected leaders and potential presidential candidates offered full-throated condemnations, accusing Trump of brazenly breaking international law by seizing the leader of another country. A second group, led by California Gov. Gavin Newsom, was more cautious, taking pains to denounce Maduro while warning that a long-term engagement in the country could prove disastrous.

The crack is symptomatic of a deeper uncertainty that has bedeviled the party for more than a decade, as Democrats struggle to counter an “America First” movement that has scrambled the country’s traditional foreign policy divisions.

“We really have to reassert ourselves in terms of what our foreign policy credentials are as a party,” said Sen. Ruben Gallego (Arizona), a potential 2028 contender. “And the one area we need to get back into is that the U.S. is a stabilizer in the world, not the rogue nation being led by Donald Trump right now.”

Since Trump began dismissing foreign policy experts and upending alliances, he has pushed Democrats into defending the foreign policy establishment. They have at times sought kinship with disaffected Republican hawks while trying to prevent what they argued would be catastrophic long-term consequences of Trump’s approach. They have wrestled with even older demons from the George W. Bush era, when they debated whether withholding support for wars in Iraq and Afghanistan would make them look weak or unpatriotic.

In the meantime, internal divisions have festered, including a struggle over support for Israel that threatens to persist through the 2028 election.

Gallego blamed the lack of a cohesive foreign policy over the coronavirus pandemic, which consumed the end of Trump’s first term and much of President Joe Biden’s first two years in office. He also said the party has been bogged down in a two-year debate over U.S. military aid to Israel after Biden’s unflinching support of the country divided the party.

“Standing on principle, especially when it comes to these very thorny issues and being very clear, will always be more popular than an ambiguous process-oriented position,” he said.

Several other prospective presidential candidates embodied that stance as it relates to Venezuela, including Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, who denounced “regime change wars” in a local radio interview, and Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker, who said “unconstitutional military action” would put “our troops in harm’s way with no long-term strategy.”

But one of the leading prospective 2028 candidates, Newsom, issued a more tempered statement after last weekend’s Venezuela raid.

“Maduro is a thug and a criminal,” he said. “But Donald Trump proposing to ‘run’ Venezuela without a coherent long-term plan beyond an oil grab is dangerous for America. The path forward must be democracy, human rights, and stability.” Energy Secretary Chris Wright said Wednesday that the Trump administration will take control of all existing flows of oilfrom Venezuela for the foreseeable future, and Trump told the New York Times the same day that the U.S. would be running Venezuela for years.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, another potential presidential 2028 candidate, went even further, calling the raid “a moment to celebrate” before expressing concern about Venezuela’s future.

Rahm Emanuel, a former Obama chief of staff who is also mulling a 2028 run, said the party should leave the nitty-gritty policy fights to the think tanks and instead argue that Trump “is fixated on Venezuela. We are fixated on Virginia” to appeal to voters concerned with the economy.

Some liberals criticized Newsom in particular for not explicitly condemning Trump’s decision to arrest and extradite Maduro using military force.

“That’s the message that Democrats lost with in 2004,” said Matt Duss, executive vice president at the Center for International Policy think tank and a former foreign policy adviser to Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont). Sen. John F. Kerry of Massachusetts ran against President George W. Bush that year. Kerry had voted for the Iraq War, complicating his ability to criticize Bush for it.

“It’s not a good idea that was executed poorly — it was a bad idea,” Duss said of the raid.

Many Democrats, however, are “nervous about looking weak” on foreign policy, said Michael O’Hanlon, a foreign policy expert at the liberal-leaning Brookings Institution. That has made them cautious in general.

Republicans have used national security as a cudgel against Democratic presidential candidates for decades.

“They don’t want to get burned on national security,” O’Hanlon said.

The Venezuela issue is particularly tricky, because many Democrats do not want to be seen as defending a dictator by objecting to the operation itself. Some in the party are also worried that any focus on foreign policy will distract from their critiques of Trump’s management of the economy, which proved effective in several off-year and special elections last year.

There is also a broader hesitation to criticize a U.S. military operation.

“The opposition party is very leery right after a military operation of saying anything, because they worry they’ll look unpatriotic, they’ll be attacked, or they’ll look like they don’t care about national security,” said Julian Zelizer, a presidential historian at Princeton University. “And they’re waiting to see what happens, because, ultimately, the president will receive the blame for any issues that emerge.”

Just 11 percent of Democrats said they support the strike in a recent Reuters poll, and more than 70 percent of Americans overall said they were concerned the U.S. could get too involved in Venezuela. Overall, Americans were about evenly divided on the strike, with about a third supporting it, a third opposing it, and a third not having an opinion.

Democrats representing states and districts with sizable Venezuelan American populations were especially clear in their approval of Maduro’s ouster.

“The capture of the brutal, illegitimate ruler of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, who oppressed Venezuela’s people, is welcome news for my friends and neighbors who fled his violent, lawless, and disastrous rule,” Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (Florida) said in a statement. She criticized the administration for bypassing its obligation to consult Congress about the action, however, and for seeming to support the continuation of the Maduro regime through Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodríguez.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (New York) initially criticized Trump for bypassing Congress in a statement that also condemned Maduro. This week, he told reporters that Maduro “oppressed” and “decimated” his country, but “the overwhelming majority of Americans do not support another failed foreign war putting our men and women in uniform at risk.”

The Democratic Party has often ping-ponged back and forth between being anti-war and more hawkish, reacting to the success or failure of the most recent war. Many Democrats were staunchly anti-war after Vietnam, and most voted against the 1991 authorization for the Gulf War under President George H.W. Bush. That brief entanglement was later branded a success, a fact that hung over Democrats as many voted to authorize the war in Iraq in 2002. Most Democratic senators backed that vote, including Kerry and Hillary Clinton. They were later haunted by those votes when public sentiment turned against the Iraq War and they later ran for president.

“Two people ran thinking they needed to show they were going to be strong commanders in chief in my recent lifetime — John F. Kerry and Hillary Clinton. And they both didn’t become president,” said Rep. Ro Khanna (California), a potential 2028 candidate who’s urged all 2028 Democratic contenders to take a strong position against the raid.

Instead, Barack Obama won the election in 2008 on an anti-war message. He later committed even more U.S. troops to Afghanistan. Trump and later Biden both campaigned on withdrawing those troops.

Some Democrats became more hawkish in reaction to Trump’s attacks on the U.S. intelligence community in his first term, when he railed against an investigation into Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. The threat of Russia — once dismissed by Obama as a relic of the Cold War — became central to Democratic rhetoric.

Trump’s “America First” platform appealed to some left-wing anti-war voters in 2016 and 2024, and Trump’s stepped-up use of military force in Venezuela and elsewhere may provide an opportunity to win them back, Duss said.

“There’s a huge opportunity here for a Democrat to offer a really robust vision for America’s role in the world,” Duss said.

Juan Gonzalez, a former senior White House official on Latin America under Biden, said Democrats’ message will become clearer if the situation inside Venezuela continues deteriorating.

“The Democrats will continue to find their voice as this administration completely runs into a wall on Venezuela,” Gonzalez said. “Democrats traditionally tend to be very process oriented. They want the international system to work, and we want to reduce this idea of American exceptionalism.”

But he said Trump’s brazen displays of American strength in Venezuela and elsewhere have inspired debates in some Democratic circles about whether the party should embrace a more muscular vision of U.S. foreign policy.

“What Trump reminds us in a bad way is that the United States can be a ruthless international actor,” he said. “Sometimes we need to do that — but the way Trump employs that backfires.”

Marianna Sotomayor contributed to this report.

The post Cracks in Democrats’ Venezuela response reveal foreign policy muddle appeared first on Washington Post.