Republicans on Capitol Hill on Thursday did something they have done little of in recent years: They tried pushing back against President Trump and standing up for their own, coequal branch of government.

In the House, dozens of Republicans voted with Democrats on Thursday afternoon in an attempt to override Mr. Trump’s first two vetoes of his second term. But with most of the G.O.P. siding with the president, they ultimately did not have enough votes to clear the two-thirds threshold necessary for either override to succeed.

That action unfolded hours after five Senate Republicans joined Democrats in a vote to advance a resolution that would block Mr. Trump from taking any further military action against Venezuela without first seeking congressional approval.

The move was described by one of the president’s allies, Senator James Risch, Republican of Idaho, as designed to “slap the president in the face.”

Mr. Trump apparently interpreted it as such: He immediately posted on his website, Truth Social, that the five Republicans who voted to advance the resolution, including his party’s most vulnerable senator facing re-election this year, Susan M. Collins of Maine, “should never be elected to office again.”

Neither move was likely to greatly constrain Mr. Trump. Widespread Republican opposition to the war powers measure, now on track for a Senate vote next week, means it has little chance of being enacted. And though a large bloc of Republicans voted to overturn the president’s vetoes in the House, a majority switched positions on legislation they had previously backed in order to stay aligned with Mr. Trump.

But taken together, the action suggested that, as an unpopular military incursion unfolds abroad, and an continuing affordability crisis festers at home, some Republicans in Congress worried about their own looming re-election campaigns were seeking a bit of distance from Mr. Trump and his policies.

The House on Thursday also was expected to pass a bill that the president and top Republicans oppose — and tried to block from coming to a vote — to extend Affordable Care Act subsidies that expired at the end of last year. That measure was forced to the floor when a coalition of politically vulnerable Republicans teamed up with Democrats to go around G.O.P. leaders and force a vote on an issue that they said their constituents desperately wanted to see addressed.

And the House passed a spending package on Thursday that rejected steep cuts requested by Mr. Trump, part of a bipartisan agreement aimed at averting a government shutdown before a Jan. 30 deadline.

On the vetoes, the resistance came from some of Mr. Trump’s longtime loyalists, who rose to protest what some lawmakers characterized as legislative retribution by the president.

One of the bills would authorize a pipeline project that would provide clean drinking water to Colorado’s eastern plains. The pipeline affects the water supply in the district represented by Representative Lauren Boebert, Republican of Colorado, who in November defied the president’s pressure and signed onto a discharge petition to force a vote on the release of the Epstein files.

The other would expand land reserved for the Miccosukee Tribe in Florida, which joined a lawsuit earlier this year to block the Trump administration from constructing an immigrant detention center in the Everglades nicknamed Alligator Alcatraz.

Both measures were so uncontroversial that they passed unanimously last year in both the House and the Senate.

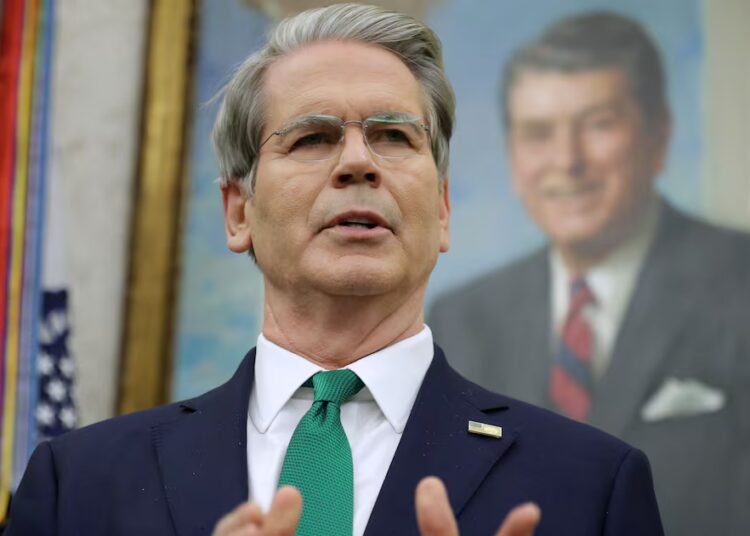

Speaking on the House floor, Representative Jeff Hurd, Republican of Colorado, told his colleagues that voting to override Mr. Trump’s veto was “not about defying the president, it is about defending Congress.”

He added: “This override is about finishing what we started. Yes, it’s also about protecting this institution.”

Democrats and Republicans alike said funding the pipeline project, which has been underway for decades with consistent bipartisan support and had even been celebrated by Mr. Trump himself in the past, was a no-brainer.

The project would help with serious water quality challenges in the area, where water is contaminated with pollutants. The Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan organization, said last year that the bill would not result in any measurable increase in federal spending.

But Mr. Trump, in vetoing the bill, claimed that he was doing so in order to save taxpayers’ money.

“Enough is enough,” he wrote in a letter to Congress at the end of last year. “My administration is committed to preventing American taxpayers from funding expensive and unreliable policies.”

Representative Jared Huffman, Democrat of California, warned on Thursday that what was at stake was bigger than a local water project. It was, he said, about allowing initiatives that affected real people’s lives to be turned into weapons of political payback.

“This is a Spartacus moment for the members of this body, ” Mr. Huffman said. “Any of us could face this.”

In the end, the watershed moment did not materialize. Thirty-five Republicans joined all Democrats to vote to override Mr. Trump’s veto on the water measure, but 177 of them voted against the bill they had previously supported.

Mr. Hurd and Ms. Boebert had both been working in recent days to rally support among House Republicans to override the veto.

It is extremely rare for a president to veto bills that pass both chambers with unanimous support, and Mr. Trump’s veto of the bill days after Christmas took Ms. Boebert by surprise.

She had assumed that she would soon be attending a signing ceremony at the White House, not approaching the microphone on the House floor to take a very public stance in opposition to a president she has long supported.

On Thursday, Democrats said Mr. Trump had vetoed the bill to punish Ms. Boebert.

“This veto has nothing to do with fiscal policy, nothing to do with the merits,” Mr. Huffman said. “We know what this veto was about. The message that this sends to Colorado is deeply troubling.”

Unlike former Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, the Republican from Georgia who dramatically broke with Mr. Trump on a number of issues, including the Epstein files, and then resigned from Congress, Ms. Boebert had gone out of her way to smooth over any rift that had opened up between herself and the White House on the Epstein issue.

But after the veto, she pushed back hard on Mr. Trump.

“Nothing says ‘America First’ like denying clean drinking water to 50,000 people in southeast Colorado, many of whom voted for him in all three elections,” Ms. Boebert said in a statement. “I must have missed the rally where he stood in Colorado and promised to personally derail critical water infrastructure projects.”

She added, “I sincerely hope this veto has nothing to do with political retaliation for calling out corruption and demanding accountability.”

On Thursday, Ms. Boebert was more tempered in her remarks on the House floor before the vote. Instead of taking an aggressive stance toward Mr. Trump, she tried to frame the move to override his veto as a vote in favor of his policies.

“This bill also makes good on President Trump’s commitment to rural communities, to western water issues,” she said. “President Trump’s commitment to western water supply and reliability will be upheld.”

Mr. Trump said in December that his veto of the bill to expand Miccosukee Tribe land was tied to its opposition to his immigration agenda. On Thursday, Representative Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Democrat of Florida, said that the bill was so narrowly tailored that the president’s argument made no sense and that it was driven by nothing “other than the interest in vengeance.”

Ms. Wasserman Schultz called it an “inappropriate and unfortunate veto.”

In the end, just two dozen Republicans appeared to agree with her and voted to overturn it. But another 188 G.O.P. lawmakers sided with Mr. Trump.

Annie Karni is a congressional correspondent for The Times.

The post Congress Tries — but Fails — to Take a Stand for Its Own Powers appeared first on New York Times.