Maurice Vasquez dances in his prison cell to blaring rap music, wearing a straw hat and designer glasses.

“Only motherf— in here with these $1,200 Cartier frames,” Vasquez says in a video filmed on a contraband cellphone. In other clips, he displays a thick gold chain — “Tiffany and Company,” he claims — and drinks prison-distilled liquor.

Vasquez isn’t the first California prisoner to enjoy forbidden luxuries. The Mexican Mafia, Aryan Brotherhood and other gangs have long trafficked drugs, alcohol and, in more recent years, phones, which allow inmates to carry out shakedowns, gambling rackets and killings on the streets of L.A. County.

But Vasquez is a new breed, law enforcement officials say, one whose organization has thrived in a system intended to protect vulnerable inmates. His group, the Riders, is largely composed of men who have renounced membership in other gangs.

California houses tens of thousands of inmates in protective housing. Some are sex offenders or informants, while others are former gang members who “dropped out” and cannot live safely in the general prison population.

Transferred to protective custody, some inmates started new crews. Vasquez’s Riders are one of the fastest-growing and most dangerous of these so-called dropout gangs, according to law enforcement officials, who say the group is responsible for stabbings and contraband smuggling behind bars and for robberies, shootings and drug sales in Northern California.

Dropout gangs pose one of the most vexing problems for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

CDCR created the first dropout yards — the official term is “sensitive needs yard” — in 1999. Authorities predicted gang members would be more likely to reform if they knew they could serve their time peacefully and away from past associates. Although intended to be a refuge from cutthroat prison politics, dropout yards have become just as violent as general population, CDCR’s inspector general found.

Gangs shake down sex criminals for protection money and kill one another in interminable struggles over power and petty slights, according to law enforcement authorities. Conflicts on “sensitive needs” yards contributed to a surge in violence in 2025, and some inmates and their families have won payouts in lawsuits alleging prison officials failed to keep them safe.

Law enforcement officials say dropout gangs can be just as violent as traditional prison outfits like the Mexican Mafia, which consider gratuitous bloodshed bad for business. The Riders and others like them are less concerned with making money than polishing a reputation, said Louis Avila, a Los Angeles County deputy district attorney who prosecuted Vasquez.

“It’s about respect,” Avila said. “You’re pumping out your chest more and you have much more unregulated violence.”

Vasquez rejects the “dropout” label. In interviews with The Times, he said Riders — who are sometimes called the Northern Riders and Norteño Riders — are not a gang but a “movement” that rose up 25 years ago against oppressive prison gangs. Riders are not dropouts, Vasquez said, but men seeking the right to be “left the f— alone.”

Former members describe the Riders as a cult of personality that revolves around Vasquez, 51, who calls himself “The Playboy President” and “Bad Ass Snoop.” Vasquez preaches a gospel of entrepreneurship and self-sufficiency in typewritten “epistles” to his followers, who “talk about him like he’s God,” a onetime member of the gang testified at Vasquez’s trial in 2021. Convicted of conspiring to commit murder, Vasquez is serving a sentence of 65 years to life.

At the 2021 trial, a prison investigator said the Riders have about 300 members behind bars and more on the streets. According to a 2016 FBI report reviewed by The Times, Riders have committed shootings and home invasion robberies in Sacramento, San Joaquin and Stanislaus counties.

The Riders and similar groups have grown along with the state’s protective custody population, which has ballooned to 30,000, roughly 1 in every 3 inmates. Another 40,000 state prisoners live on what are known as “50/50 yards,” a mix of “sensitive needs” and general population, said Terri Hardy, a CDCR spokeswoman.

Thirty-one state inmates were killed in California in 2025, which was the most violent of the last five years. Four victims were classified as “sensitive needs,” while another three were slain on integrated yards, Hardy said.

CDCR officials declined to be interviewed. In a written statement, Hardy said CDCR leadership locked down high-security prisons after a string of killings, revoking privileges as investigators searched cells, screened mail and monitored surveillance cameras to root out weapons, phones and other contraband.

None of those measures have seemed to slow down Vasquez. When he was sentenced in 2021 for ordering the murder of a rival, the judge who heard his case voiced doubts about the state’s ability to control him.

“He continues to recruit people,” she said. “I don’t think that that has stopped.”

Vasquez says he founded the Riders on his 25th birthday.

It was 1999, and he’d just finished a three-year prison term for grand theft. Vasquez posted fliers around his hometown of Sacramento promising an “extravaganza,” he told The Times. He rented speakers, hired a DJ and printed 100 hats and T-shirts for the event, which drew some 700 people, he said.

They listened as Vasquez warned that behind bars, they’d find an upside-down world where “losers are somehow considered the cool crowd.”

Vasquez said he was shocked to learn that the “self-appointed shot callers” in prison were men who had washed his car’s rims for pocket change on the street.

Vasquez said he had been an entrepreneur since he started hustling as a 10-year-old by selling candy and Ritalin to prostitutes in downtown Sacramento. Describing himself as “a bit of a debonair,” Vasquez said he later operated a chauffeur business for strippers and an escort service called Exquisite Elements.

But in prison, his independent streak ran up against the Nuestra Familia, the dominant prison gang in Northern California. Ordered to kick up money and contribute to a “kitty,” a pot of commissary goods collected from every inmate, he said he was “appalled.”

Vasquez came to see prison gangs as subjugating many for the benefit of a few.

“These guys are given absolute power,” he said. “And I’m sure you’ve heard the saying: ‘Absolute power creates absolute destruction.’”

At the park, Vasquez announced he was starting an “anti-prison gang” movement called the Norteño Riders. He circulated copies of a declaration that he quoted from memory, two decades later: “Henceforth, we will not tolerate being referred to as banditos, no good, dropout or other monikers that have been created to label us as anything less than the men that we are.”

Prison gangs have always produced dropouts.

Some inmates are forced to turn to the authorities for protection after losing internal power struggles or running up debts. Others hope to earn a chance at parole or simply grow tired of looking over their shoulders.

Before 1999, authorities removed inmates from general population under limited circumstances, said Leo Duarte, a retired CDCR official who vetted requests for protective housing.

This changed with the “sensitive needs” program. According to an inspector general report issued 16 years later, CDCR’s leadership told lower-level officials to take a “liberal” approach to granting protective custody. All an inmate had to do was invoke a threat, real or perceived.

Duarte said he warned administrators with little experience working in prisons that they were “opening a can of worms.”

While assigned to the California Institute for Men in Chino, Duarte witnessed the birth of one of the largest dropout gangs. Founded by four disaffected camaradas, or associates of the Mexican Mafia, they called themselves the Two Fivers. The name was a play on peseta, a 25-cent coin — prison slang for an inmate in protective custody.

The Two Fivers drew recruits with different motivations, according to a member of the gang who requested anonymity because he feared retaliation. Some wanted to stay involved in the drug trade. Others, having belonged to gangs their whole lives, couldn’t imagine going through prison alone.

“The whole gang thing to begin with is about a sense of family,” said Avila, the L.A. County prosecutor. “They drop out when they see it’s all a lie. But they’re still a person that’s in search of that, that sense of connection.”

The Two Fiver who spoke to The Times said his motive was revenge. After being accused of stealing from the Mexican Mafia, “I wanted to do everything and anything I could to hurt their organization,” he said.

After his release from prison, he said he robbed drug dealers and collected “taxes” by impersonating a Mexican Mafia member. Today, he said, some gangsters who don’t want to take orders or be extorted become Two Fivers without even going to prison.

At least one member of the Mexican Mafia considered the defections to be an existential threat. The organization of about 140 men relies on many more followers to collect money, sell drugs and carry out hits.

Without them, “we wouldn’t have a thing,” Braulio “Babo” Castellanos, a now-deceased Mexican Mafia member, wrote in a manuscript seized by law enforcement. “We are losing a lot of them. Let’s try and turn the tide instead of letting them think the other side is an alternative.”

If the 1999 park meeting was Vasquez’s declaration of independence, a prison melee was his call to arms.

After announcing his “movement,” Vasquez said he got into a shootout with armed men who showed up at his house. Sent to Deuel Vocational Institution in Tracy, Vasquez said he refused protective custody.

When guards asked Vasquez if he wanted to stay in his cell or go to the exercise yard, “I had a choice,” he said. “I was either going to man up, take my medicine, or basically I was going to be chased for the rest of my life.”

In Vasquez’s telling, he went to the yard and fought off every prisoner who attacked him.

His organization is now called the Riders because it draws recruits from beyond Northern California. Unlike traditional prison gangs, the Riders don’t define themselves by a racial or geographic identity.

Released from prison around 2002, Vasquez was convicted two years later of kidnapping a man in Santa Clara County. Sentenced to 19 years, he said he remained in general population until 2008, when he learned inmates in protective custody were falsely claiming to be Riders. To hear Vasquez tell it, he transferred to a dropout yard only to confront “impostors.”

Today, nearly all Riders are housed on “sensitive needs” yards, Vasquez said. “SNY has saved lives,” he said. “I strongly doubt I would be talking to you if I had continued allowing CDCR to send me to general population yards.”

In 2010, Vasquez created a formal structure, designating 18 members as his “disciples,” said Terry Gonzales, a former member who testified that he was once Vasquez’s right hand man. Gonzales claimed he tithed to Vasquez 25% of some $250,000 he made selling drugs.

Vasquez called the allegation “bull—.” The Riders have no leader or chain of command, he said; if he ever demanded a cut from another man’s business, “they’d laugh at me.”

Vasquez said he encourages every Rider, or “compadre,” to be enterprising. He authored a book from prison, “Basic Fundamentals of the Game,” that is sold on Amazon for $12. Vasquez said he became a “connoisseur of language” after being locked in a jail cell at 16 with only a Bible and a dictionary.

In a document called the “Compadre Concepts and Objectives,” Vasquez laid out a vision for his group: “We seek to eventually evolve into a self sufficient society of Riders where the success and wealth of each compadre serves as the burning motivation for us all.”

Former members testified that Vasquez and his associates make plenty of money selling phones, drugs and other contraband smuggled by corrupt staff. Vasquez declined to reveal how he obtained Cartier glasses, Tiffany jewelry and phones, saying, “Where do you think it comes from?”

As the Riders grew, their influence stretched beyond prison walls. In a 2016 report, FBI agents said their members were getting into shootouts with rival Norteño gangs as they feuded for territory in Stockton, Sacramento and Modesto.

After a Rider shot at Stockton police officers in 2017, authorities began tapping phones used by the organization, court records show. A detective wrote in a wiretap application that the Riders drew disillusioned gang members who considered Vasquez a “martyr.”

But when one of his followers split off to form a new gang, authorities charged in a complaint, Vasquez ordered his death.

The rise of groups like the Riders has created a new problem for prison officials: Where do they put dropouts from dropout gangs?

Richard Armenta renounced his Imperial County street gang after testifying against another gang member, according to records he filed in a lawsuit against the state. The convicted murderer then joined not one but two dropout gangs, the records state.

After he quit the Two Fivers and the Independent Riders, CDCR officials wrote in prison records that Armenta “should NOT return to any general population [GP] facilities or sensitive needs yard [SNY] facilities due to enemy and safety concerns.”

Armenta sued in 2024, claiming CDCR was violating his rights by holding him in solitary confinement indefinitely.

Hardy, the CDCR spokeswoman, declined to comment on Armenta’s lawsuit, which remains pending.

In a message to The Times, Armenta faulted CDCR for having no policy other than to keep him in “the hole.”

Dropout gangs have created other costly legal headaches for the state.

Andy Gomez dropped out of the Two Fivers in 2018 after deciding he “wanted more out of life than to be a member of a prison gang,” he wrote in a civil complaint filed in federal court. He claimed that guards at Kern Valley State Prison in Delano ignored his pleas to separate him from his old gang.

“You can’t run and hide forever,” an officer told Gomez, according to his lawsuit.

The morning of May 4, 2021, Gomez said, he was ambushed by seven Two Fivers who stabbed him more than 30 times. “The only sound I could make was a muffled ‘ummp’ ‘ummp’ sound each time a manufactured knife weapon punctured through my flesh,” he wrote.

CDCR denied Gomez’s claims but settled this year by paying $7,000.

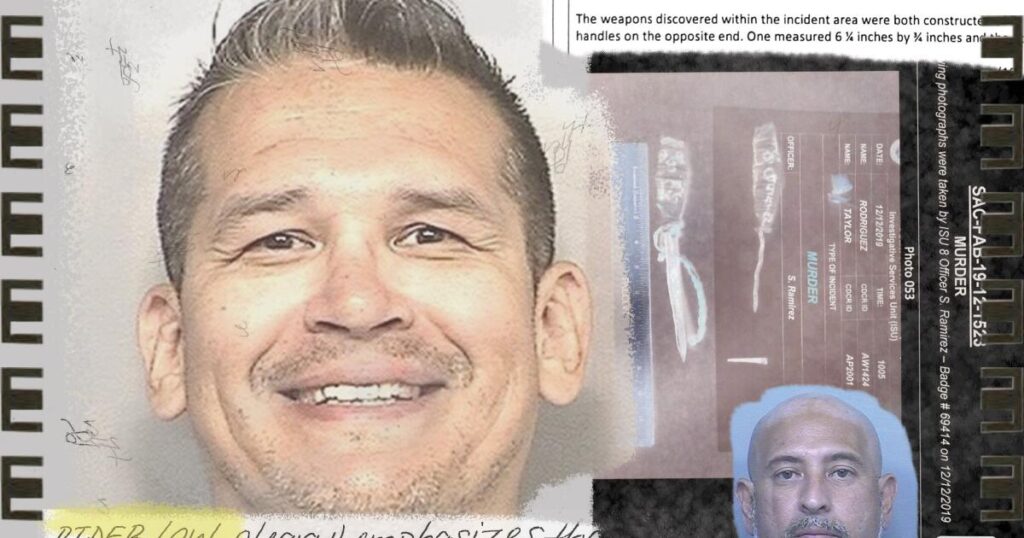

A year later, Sidney Kang was killed at the same prison. The morning of May 5, 2022, two inmates slid a pair of seven-inch metal knives under cell block doors, a CDCR investigator wrote in an affidavit. Michael Caldera, an Ontario bank robber serving 71 years, carried the weapons to an exercise yard and handed one to Anthony Ramirez, a convicted murderer from Artesia, according to the affidavit. The two stabbed Kang 18 times in the back, chest and neck, authorities say.

“I can’t breathe,” Kang gasped before vomiting blood, an officer wrote in a report.

Kang, 31, had joined the Two Fivers while serving 14 years for assault, according to prison records. Ramirez and Caldera are reputed members of a rival dropout gang, the Zapatistas. They have pleaded not guilty to murder charges.

Kang’s parents sued the state, claiming Kern Valley was consumed by gang conflict and riots. According to their lawsuit, Kang told his uncle that guards ignored his pleas for protection. If he were killed, he told his uncle, his blood was on their hands.

Kang’s family and their lawyer didn’t return requests for comment. CDCR denied the allegations but paid his family $300,000 to settle in June, Hardy said.

At Vasquez’s trial on murder conspiracy charges in 2021, L.A. County prosecutors called to the witness stand an inmate who had dropped out of his Ontario street gang while serving four years for domestic abuse.

Transferred to a “sensitive needs” yard, the witness, whose name was redacted from court transcripts for his safety, testified he shared a cell with a Rider.

If he joined, his cellmate promised, “nobody’s going to hurt you.”

“I decided to do it,” he testified.

At California State Prison, Corcoran, his loyalty was put to the test, he said. He was handed a cellphone and told to take the call from “Bad Ass Snoop, the president.”

“It’s time to shine,” he said Vasquez told him.

The witness testified Vasquez asked him to kill Alex Diaz, who had left the Riders to start a new gang called Nuestra Cosa.

“I’m always loyal to you, compadre,” the witness said he told Vasquez. The next day, he and three other Riders stabbed, beat and stomped on Diaz, who survived.

After Vasquez asked him to kill another member of the Riders, the witness testified, he dropped out and cooperated with prosecutors. Vasquez denied issuing orders to kill anyone.

Authorities have found no shortage of prisoners willing to turn on Vasquez; one even noted in an interview with investigators the absurdity of a gang leader recruiting from prisons filled with informants.

“You got snitches doing murders for you,” he told authorities, according to a tape reviewed by The Times. “They’re all swimming in the same s— bowl. They don’t have any rules.”

Three years later, Vasquez ran into an old enemy at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility. Guy Perez, a convicted killer and kidnapper from Merced County, was an “impostor” who’d claimed to be a Rider, Vasquez said.

What happened next illustrates the logistical nightmare of “sensitive needs” yards, where inmates routinely disclose their enemies and expect prison officials to keep them separated.

According to Vasquez, Perez had been disciplined in 2018 for conspiring to murder him. The two were documented enemies, Vasquez said, so he was “astonished” when Perez arrived at the prison in 2024.

“It was brought to my attention he was making threats. I went to go confront him, which led to his demise,” he said. Vasquez suggested he was defending himself from Perez. “It easily could have been me,” he said.

Vasquez and another inmate, Michael Mendoza, have pleaded not guilty to charges of murdering Perez and are scheduled to stand trial in June 2026, according to a spokeswoman for the San Diego County district attorney.

Vasquez said the responsibility fell on prison officials for not separating two enemies. Hardy, the CDCR spokeswoman, said she would not comment on an active investigation.

Vasquez said it is easy for someone who has never been to prison to judge the actions he’s taken to survive.

“In this cesspool, this underworld,” he said, “the guy that’s shaking your hand is the same guy that’s running up behind you and slitting your throat. The same guy that’s sharpening his toothbrush so he can shove it in your eye.”

The post Cartier glasses, stabbings and payouts: ‘Dropout’ gangs sow chaos in California prisons appeared first on Los Angeles Times.