The day after U.S. special forces swept into Caracas, the new Venezuelan president assembled her cabinet members around a large wooden table at the Miraflores Palace. Behind Delcy Rodríguez were large pictures of the country’s fallen leaders: Hugo Chávez, dead of cancer in 2013, and Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, now jailed in New York on drug-trafficking charges.

Seated on either side of Rodríguez, at the head of the table, were the powers that remained. One was Vladimir Padrino, the defense minister, dressed in military camouflage. The other was Diosdado Cabello, the interior minister. He wore a scowl and a hat that said, “To doubt is treason.”

Both men hold far more power than their titles suggest, analysts say. Stalwarts of the Maduro regime — one U.S. investigators say is built on patronage and fueled by criminal proceeds — they control Venezuela’s expansive security state and much of its commercial activity.

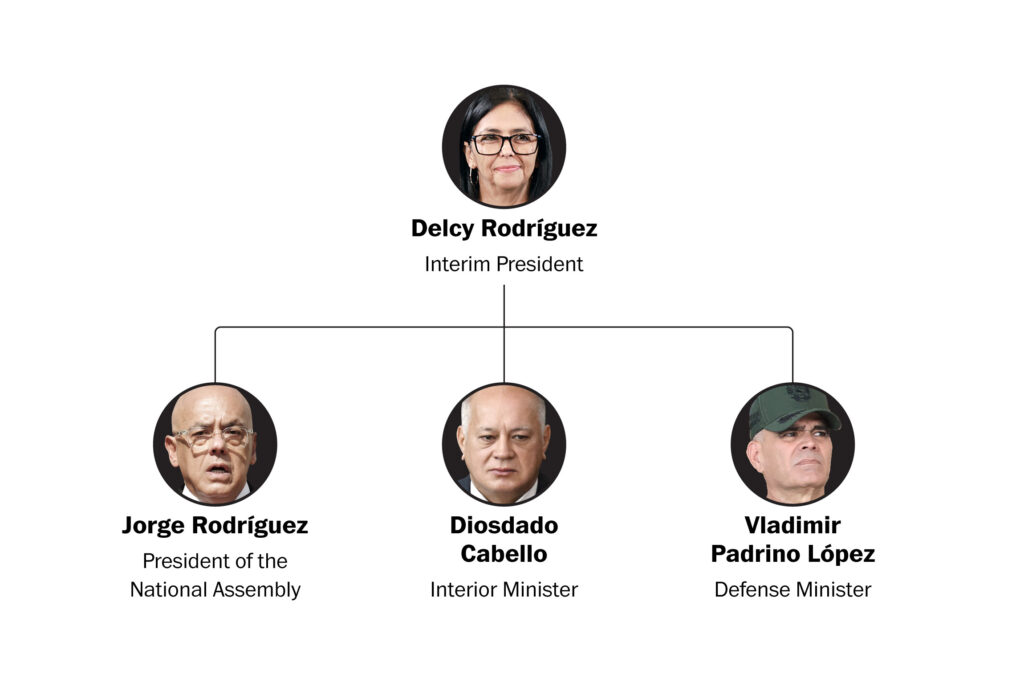

Since Maduro’s capture and arrest Saturday, public attention has focused on Rodríguez and whether she will accede to White House demands to open up Venezuela’s vast natural resources to American industry. But the newly installed president — alongside her brother Jorge, president of the Venezuelan National Assembly — represents only the political sphere.

The country’s other power centers, according to scholars, Venezuelan researchers, and current and former U.S. officials, are commanded by Padrino and Cabello — hard-line, old-school Chavistas who came of ideological age in the socialist movement and accrued significant power and wealth through continued loyalty to the cause.

Using connections and intimidation, researchers say, the men have repeatedly helped Maduro survive periods of crisis and tighten his authoritarian grip. First in 2019, when much of the world united behind opposition leader Juan Guaidó’s bid to supplant Maduro. And then again in summer 2024, when electoral tallies made clear that Maduro had lost the presidential election.

Now Padrino and Cabello, both of whom are wanted by U.S. authorities on drug-trafficking allegations, will help to decide the future of Chavismo — and the nation. Their continued presence magnifies the complexity of the challenge faced by American negotiators as they seek to bypass war and regime change and find common ground with members of a besieged government riven by internal divisions.

“There are three centers of power,” said a former senior official with the U.S. State Department, who like others in this story spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters. “And Delcy is going to find out pretty quickly that she can’t provide everything that the Americans want.”

The Washington Post was unable to reach Padrino and Cabello for comment. The communications office of the Venezuelan government did not respond to a request for comment.

President Donald Trump has said the United States is “in charge” of Venezuela, while Secretary of State Marco Rubio has suggested a less direct role, saying the U.S. will use its ongoing oil blockade and other economic measures to make Caracas do its bidding.

Analysts expressed concern that Washington doesn’t fully understand the factional, internecine political system it now seeks to control — a maze of overlapping loyalties, family ties and competing interests. Several pointed to Cabello — a feared figure who hosts a weekly talk show called “Bringing the Hammer” — as the wild card.

One Venezuelan adviser close to Rodríguez’s government said he was central to maintaining unity. “In times of crisis, his role is not conciliatory, but rather one of maintaining order,” the adviser said. “Delcy governs; Diosdado ensures that power does not slip away.”

But others worry about what he was capable of. At his disposal, according to researchers and U.S. officials, were not only the police and intelligence services, but also the “colectivos,” a pro-government militia embedded throughout society, whose members speed around the streets on motorcycles, armed and masked.

“Cabello is a brutal, repressive figure in the regime, but he’s not stupid,” said Geoff Ramsey of the Atlantic Council. “He knows his survival depends on threatening to burn down the country, unless his interests are taken care of.”

“Politics in Venezuela,” he added, “is a ruthless blood sport.”

Power at all costs

How the state built by Chávez went from a hierarchal system built around a single charismatic leader to a hotbed of competing factions is, to some degree, a story of Maduro’s own political failings.

“Chávez was a leftist military man and very charismatic and happened to rule Venezuela during an oil boom, so he had a lot of resources to do a lot of things,” said David Smilde, a sociologist at Tulane University who researches Chavismo. “And with the exception of being a leftist, Maduro is none of those things — not charismatic, not a military man, and he has no oil boom.”

After narrowly winning the presidential election to succeed Chávez in 2013, Maduro appeared to recognize what he lacked and set out to defend his hold on power not through political persuasion, but by restricting freedoms and empowering — and enriching — the armed forces.

In February 2016, he put the mining sector in the hands of the military. A few months later, he gave it control over the distribution of basic goods. Another decree shortly afterward put the nation’s ports under its purview. Padrino, who rose to defense minister in October 2014, became more powerful with each move, researchers said, pioneering new kickback schemes that kept the military loyal to him and indebted to the regime.

“The military became its own branch of power,” said Carolina Jiménez Sandoval, the Venezuelan president of the Washington Office on Latin America. “I don’t think the United States understands the extent to which the military is ingrained into the politics and economy, both formally and informally.”

The military also began to profit from illicit revenue streams, American authorities contend. In March 2020, federal prosecutors in the U.S. District Court of the Southern District of Florida filed charges against Padrino and Cabello for using their roles to facilitate and abet Venezuelan drug trafficking and “flood” the United States with cocaine.

The U.S. government announced significant bounties for both men — $15 million for Padrino and $25 million for Cabello.

Over time, Maduro came to be seen less as the ultimate authority in the country and more as an arbiter between competing powers that had little in common, said Roberto Deniz, a Venezuelan investigative journalist.

“It’s not just an authoritarian regime,” he said. “It’s an authoritarian regime with a kleptocratic structure in which there are numerous heads, and each one acts as its own fiefdom.”

“It doesn’t matter if the economy is good or bad, if human rights are respected or not,” he added. “The goal is to preserve power.”

‘The black sheep’

Cabello, who describes himself online as a “revolutionary” and “radical Chavista,” is seen by observers as a particularly unpredictable figure. He participated in Chávez’s failed coup attempt in 1992 and spent the next two years in prison. After Chávez won the presidency through the ballot box, Cabello served as vice president, helping him stave off an attempted coup in 2002, and then as interior minister, a role where he developed deeper ties with the internal security and intelligence forces.

At the time of Chávez’s cancer diagnosis, he was seen as the second most important revolutionary and a direct rival to Maduro, then the vice president, in the line of succession. After Chávez selected Maduro as his heir, he moved to sideline Cabello, only bringing him back into his cabinet shortly after his apparent electoral loss in 2024.

“Cabello has been the black sheep in the ruling party,” Ramsey said. “But Maduro found it impossible to rule without his knack for repression and his proximity to the intelligence apparatus.”

His family’s influence spans the nation. Alexis Rodríguez Cabello, a first cousin, is in charge of the Venezuelan intelligence service and posts frequent homages to Cabello on social media. His brother, José David Cabello, is in charge of the powerful customs and taxation ministry, granting him control over duties at borders and ports. His wife Marleny Contreras, a current member of the national assembly, has been the minister of both tourism and public works.

The Post was unable to reach Cabello’s family members for comment.

“Diosdado never stopped being a powerful actor, even when he seemed demoted,” Deniz said.

And he has “ascended rapidly” since his formal return to government, added Rafael Uzcátegui, the former director of Provea, a prominent Caracas nongovernmental organization — “at the cost of Rodríguez.”

Uzcátegui saw a narrow path forward for brokering an agreement between Venezuela’s rival power centers that would enable cooperation with U.S. officials and avert a wider conflict.

“It’s much easier to negotiate with a ‘malandro’ than a religious fanatic,” he said, using a word that most closely translates to “hustler.” “And the Diosdado Cabello and Padrino factions are most motivated by material incentive.”

But there have been worrying early signs, most notably from the informal militias that answer to Cabello.

The colectivos have fanned out across Caracas. Ordinarily, they carry small arms to intimidate dissenters, but they have been seen with larger weapons in recent days, including assault rifles. They have set up checkpoints, forcing residents to turn over their phones and searching them for messages that could be seen as supportive of the U.S.

Security forces also have arrested civilians and detained members of the media.

“Diosdado Cabello could be the spoiler,” said the former senior U.S. diplomat. “It’s a pretty rough start for what is the same regime, but a different management.”

The post Venezuelan politics are a ‘blood sport.’ The U.S. is entering the ring. appeared first on Washington Post.