President Trump spent his first year back in the White House coming up with new ways to chip away at the Federal Reserve’s political independence and pressure the central bank to accede to his demands for lower borrowing costs.

His second year in office is poised to put the Fed’s autonomy to an even more extreme test — one that many worry will undermine the central bank’s ability to base monetary policy decisions on what is most appropriate for the economy, rather than what will benefit the White House.

The central bank faces two major hurdles early on in 2026. One stems from the choice Mr. Trump will soon make about who will replace Jerome H. Powell as chair of the central bank. Mr. Powell’s term does not end until May, but the president has closed in on his pick after a monthslong, highly publicized audition for one of his most consequential appointments.

The other hurdle involves Lisa D. Cook, a member of the Fed’s board of governors whom Mr. Trump tried to fire last year. The president, citing unsubstantiated allegations of mortgage fraud, has said he has “cause” to remove Ms. Cook, who was appointed by the Biden administration. Ms. Cook’s lawyers, and many legal experts, instead argued that her ouster was a flimsy pretext to exert more pressure on an institution that has so far rebuffed Mr. Trump.

On Jan. 21, the Supreme Court will hear arguments related to Ms. Cook’s case, the latest in a string of lawsuits tied to the president’s efforts to wrest more control over agencies that Congress established as independent.

Hanging in the balance of both of these crucial decisions is the Fed’s ability to operate free of political meddling. The Fed’s ability to make decisions that are in the best interest of the economy, not just those that are politically expedient, is broadly seen as the backbone of the economy’s success and the stability of the financial system.

If Mr. Trump selects a Fed chair who is perceived as pliable to the president, that risks provoking a crisis of confidence around the central bank’s grip on inflation and its stewardship of the labor market. If the Supreme Court sides with the administration in the Cook case, legal experts warn that the president will have a clear path to fire any Fed official he wants.

“It is unfortunately all too easy to envision scenarios going forward that involve a tremendous amount of damage to the institution, to the detriment of the U.S. economy and its financial system,” said David Wilcox, a former leader of the Fed’s research and statistics division who is now an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Bloomberg Economics. “If it happens, that damage would take many years, if not decades, to repair.”

Personnel Is Policy

In a unanimous vote in mid-December, the Fed’s seven-person board of governors approved the reappointment of all but one of the 12 presidents of the regional reserve banks for five-year terms. The one exception, Raphael W. Bostic, president of the Atlanta Fed, had already announced that he would retire at the end of February.

The routine decision put to rest months of angst that had bubbled up as Mr. Trump sought new ways to lean on the Fed. That has come to include not only personally insulting Mr. Powell and threatening to fire him, but also attacking his handling of costly renovations of the central bank’s headquarters in Washington.

The overarching concern was that the president could try to block the reappointment of at least some of the regional presidents in a bid to more directly influence the policy-setting process. Rate decisions are voted on by the 12-person Federal Open Market Committee, which is made up of the seven board members in Washington, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and a rotating set of four other regional presidents.

In recent months, many of these regional presidents have emerged as the primary source of opposition to the interest rate cuts that the Fed has delivered since September, causing uncharacteristically sharp divisions over the policy path forward.

Even if Mr. Trump wanted to pursue this line of attack, he lacked the internal backing to carry it out. The three governors appointed by the president voted with the majority to extend the regional officials’ terms. But the threat alone underscored the significant possibilities available to the president should he put enough loyalists on the board.

Mr. Trump will move one step closer to having his supporters in top positions at the Fed with his selection of a new chair. The president has said anybody who disagrees with him will never get the top job, prompting concern that his choice will prioritize pleasing Mr. Trump over all else.

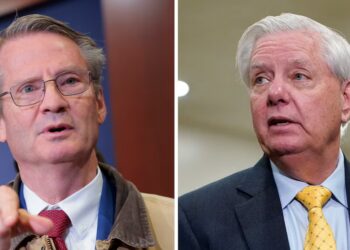

The contest is down to just a handful of candidates. Kevin A. Hassett, who has become one of the staunchest defenders of the president’s economic agenda in his role as the White House’s top economic adviser, has emerged as the front-runner. Kevin M. Warsh, a former Fed governor who has called for “regime change” at the institution, is also under consideration, as is Christopher J. Waller, a current official who was one of the earliest advocates for rate cuts this year.

Whoever gets the job will have enormous discretion over setting the contours of the policy debate inside the Fed, as well as determining staffing priorities and personnel decisions. But the next chair will be influential only so far as he can drum up support from other officials.

Pushing for more aggressive cuts than what the economy is calling for, for example, is likely to face significant opposition from the current cast of policymakers. But that pushback could wane if there is significant turnover among the top ranks because the president is able to remove Fed officials at his discretion.

Testing the Guardrails

It is this turnover that Mr. Trump is trying to expedite with his case against Ms. Cook, whose term does not officially end until 2038. In trying to fire her, the president has spurred an existential debate about what protections Fed officials should have and how insulated they should be from the White House’s whims.

“If she prevails, then we’re fine. If she doesn’t, then the whole institution could get co-opted by the administration,” said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase. “The biggest guardrail is removal protection.”

So far, the Supreme Court has given Mr. Trump extensive leeway to fire members of independent agencies, such as the National Labor Relations Board. But even the court’s conservative justices have dropped hints that they view the Fed differently, giving those who fear the erosion of the Fed’s independence some confidence that Ms. Cook will be victorious.

In an unsigned opinion in May that allowed Mr. Trump to temporarily remove leaders of two independent boards, the majority went out of its way to carve out the Fed.

“The Federal Reserve is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States,” the opinion read.

In the fall, the justices ruled that Ms. Cook could stay in her role as the litigation proceeded. Roughly three months later, Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, a conservative member of the court, was one of several justices to express concern about how the court’s rulings on other independent agencies like the Federal Trade Commission could undermine the central bank’s independence.

Without a decisive answer on the president’s ability to strong-arm officials to leave, Mahmood Pradhan, head of global macro at the Amundi Investment Institute, an asset manager, warned that sitting policymakers would remain “vulnerable” to similar attacks.

“We’ve now seen that can of worms, so that can happen anytime,” he said.

Colby Smith covers the Federal Reserve and the U.S. economy for The Times.

The post Tests of Fed’s Independence Intensify as Trump Seeks to Reshape Institution appeared first on New York Times.