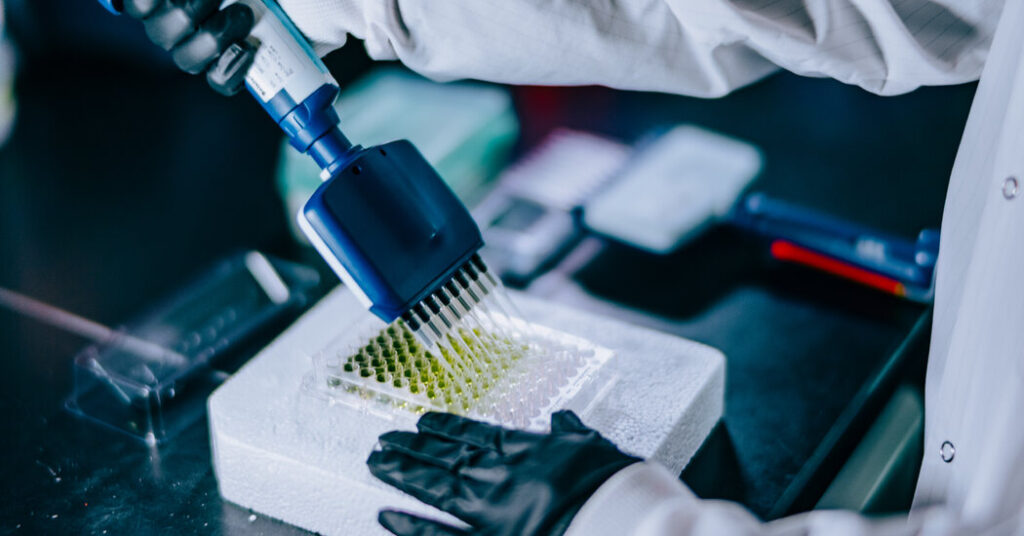

Academic research labs across the country are working to find biological markers that can predict whether a child is at risk of developing autism. And companies are rushing to turn the findings into commercial tests, despite limited evidence to back their validity, raising concerns that their results could mislead desperate parents.

They include one test that examines a strand of hair to rule out an autism diagnosis in babies as young as one month old. Two other tests just entered the market. One promises to predict autism risk based on skin cells collected as early as days after birth. Another looks for the presence of certain antibodies in a mother’s blood to determine whether her children, or babies that she might have in the future, are at risk of developing autism.

All the tests are based on autism research by scientists at academic institutions.

For decades, clinicians and parents have hoped for a biological test that could help determine if a child has autism. The push to commercialize investigators’ early research has accelerated as Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has elevated the neurodevelopmental disorder into a national political priority, creating new funding for autism research and reviving long-discredited theories about autism and vaccines.

But the new tests, largely aimed as a screening tool for the general population, are not yet reliable enough to be offered commercially, outside scientists familiar with the tests say, especially in a landscape where families are already inundated with incorrect or unverified information about autism. None of the tests has gone through large experimental trials or had its validity evaluated by a regulatory agency.

“All of these tests are interesting hypotheses,” said Joseph Buxbaum, a neuroscientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai who studies the genetics of autism. But they are “absolutely not at a point for any kind of clinical use,” he said.

Dr. Buxbaum pointed to well-established genetic tests that can identify the small subset of people with an autism diagnosis — around 25 percent of them — that carry genetic variants associated with the neurodevelopmental disorder. Those tests, he said, can give families clear cut answers about the causes of the disorder that could, for example, help inform their family planning decisions.

In contrast, he said, the new tests are based on marginal evidence — including small sample sizes and a reliance on findings from animal research — and their findings are likely to be difficult to interpret.

“Families are living in a sea of uncertainty now,” Dr. Buxbaum said. “They are burdened enough without us giving unclear messages and unfortunately probably some false hope or false despair.”

Though the tests need to be prescribed by a physician, none of them is covered by insurance. They range in price from $500 to $985. And though they are overseen by federal monitoring of quality control in labs, the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate this type of test. The only assessment of whether the tests are a valid measure of autism risk is done by the companies themselves.

In most people with autism, scientists do not know what caused their brains to develop differently. While genetic factors have been shown to play a strong role, and environmental influences are likely to contribute, the language and social challenges that characterize the disorder vary widely in severity, and there is no single molecular pathway through which autism develops.

The companies marketing the tests said they are not meant to replace clinical expertise or diagnosis, and they should be used alongside clinicians’ evaluations of children. And they defended the studies that the tests were based on, saying they were financed by the National Institutes of Health, conducted at reputable institutions and subjected to peer review before publication.

High Demand, Not Enough Data

The companies marketing the tests say they are responding to an urgent demand, much of it driven by families who want their children to have earlier access to therapies that might help them.

Autism prevalence has risen to 1 in 31 8-year-olds, according to the most recent federal data. While therapies in the first years of life can improve outcomes for many autistic children, including helping them learn to communicate, many pediatricians are too busy to do thorough developmental screenings at regular well visits for toddlers. Families that try to get specialized autism evaluations may have to wait up to a year to get off waiting lists.

The result is a delay in diagnosis: On average, children are not evaluated for autism until around age 4.

“It’s really hard to identify children early enough to really make a difference in some of these core behaviors that cause them trouble,” said Dr. Ali Carine, a pediatrician in Columbus, Ohio, who is one of 22 pilot providers across the country currently offering the new antibody test.

As an example, Dr. Carine pointed to one of her patients, a 3-year-old boy who had recently been diagnosed with autism. The child’s parents wanted to find out what caused his autism, but also wanted to know if their 17-month-old might be at risk. She suggested that the mother, Angela Davis, try the test.

The results were negative. Ms. Davis said later that her reaction to the test result was primarily relief for her young son, but a feeling of still not having answers for her older child.

Dave Justus, founder and chief executive of NeuroQure, the maker of the skin test, put it simply: “We are bringing it to market because the medical community is begging us to bring it to market.”

Mr. Justus, who has a son with severe autism, said his work was also driven by parents like himself. “Like so many families, we waited years for clarity — years when the brain is most able to make improvements,” Mr. Justus said.

The skin test looks for altered cell signaling patterns that research conducted by John Jay Gargus, a geneticist at the University of California, Irvine, has suggested can distinguish people with autism from people without the disorder.

But Dr. Gargus’s work is based on skin samples from just 60 children, and Mr. Justus said NeuroQure has evaluated its commercial test in fewer than 100 additional children.

Mr. Justus said the test was based on “decades of peer-reviewed research.” The company, he added, would have data from many more patients now that the test is on the market.

The hair test, called ClearStrand-ASD, has also been met with skepticism by some scientists.

LinusBio, the company behind the test, claims it can rule out autism with 95 percent accuracy by searching for metabolic signatures of metals and other compounds in hair that are associated with the disorder. The test is based on the work of Manish Arora, an environmental epidemiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and a co-founder of the company.

But Dr. Buxbaum and other scientists questioned how that signal would fit with the research showing that autism is largely driven by genetics. And they noted that other factors, like diet and medicine, can also affect metal signatures in hair.

“This hair test is probably picking up way more cases of God only knows what than autism,” said Alycia Halladay, chief science officer at the Autism Science Foundation.

In response, Dr. Arora of LinusBio said the test was intended to examine biological responses to environmental exposures over time, “helping bridge the gap between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors.” He noted that his research included people in countries like Mexico and Sweden, and variations in diet and lifestyle did not affect the test’s performance.

“A time comes where you say, look, if we just keep saying that, ‘the science is new, the science is new,’ are we helping the families?” Dr. Arora said.

A Promising Line of Research

The new antibody test, which is based on the work of Judy Van de Water, an immunologist at the University of California, Davis, has perhaps the most research behind it of any of the measures.

The test looks for specific antibodies, known as autoantibodies, that mistakenly attack normal cells in a person’s body as if they posed a threat. Dr. Van de Water’s research group has identified eight autoantibodies that cross the placenta during pregnancy and can target proteins involved in fetal brain development.

In studies analyzing the blood of thousands of women, Dr. Van de Water found that up to 20 percent of mothers who have children with autism produce these antibodies, compared with less than 1 percent of mothers with typically developing children. Laboratory animals exposed to the antibodies showed changes in brain structure and exhibited behaviors — like social avoidance and repetitive self-grooming — that researchers use as proxies for autism in humans.

But other scientists said that test, too, is not yet reliable enough to be used by patients, in part because much of the work that indicates the antibodies alter fetal brain development was conducted in animals. (It would be unethical to conduct such experiments in humans.)

Dr. Betty Diamond, an immunologist at Northwell Health’s Feinstein Institutes of Medical Research, has also studied a maternal autoantibody linked to autism and praised Dr. Van de Water’s work in the field. But she noted it was not clear what level of antibodies were necessary to indicate a high risk of autism, and that more data were needed to make sure the test did not produce many false positives.

“We haven’t thought that it’s right for testing yet, but obviously people can disagree about that,” Dr. Diamond said.

Michael Paul, chief executive of MARAbio, the company selling the new antibody test, said that Dr. Van de Water’s research was based on “a very, very robust data set.”

“I would feel unethical to not bring it forward,” Dr. Paul said, “because we believe this is a test that families should have.”

Dr. Paul said the company hopes to limit the number of false positives by making clear to doctors and patients that the test is not intended as a screening tool for the general population. Instead, the company is marketing the test only to women who already have a child with an autism diagnosis and are deciding whether to have more children, or those who have a child who is exhibiting clinical signs of the disorder. The company is currently validating the test for use in the general population, Dr. Van de Water, who also is the founder of MARAbio, said.

The risk of false positives is also one reason the company is not yet making the test available to pregnant women — a group that Dr. Van de Water said has been asking her for a test like this for years. But the restriction, she added, also allowed the company to sidestep thorny debates about abortion and autism.

“We do not want to go there. And we don’t have to,” Dr. Van de Water added, noting that, unlike common prenatal tests that rely on detecting fetal cells, the antibody test needs only a sample of the mother’s blood on which to base predictions.

Dr. Halladay of the Autism Science Foundation said that, though the antibody test was backed by more research than the other measures, it was also the test she was most concerned about because it could be used to make family planning decisions based on potentially inaccurate information.

“This is an interesting line of research,” Dr. Halladay said. “Should it be made into a commercial test right now? My opinion is no.”

Azeen Ghorayshi is a Times science reporter.

The post Tests for Autism? Companies Are Selling Them, but Research Is Still Scant appeared first on New York Times.