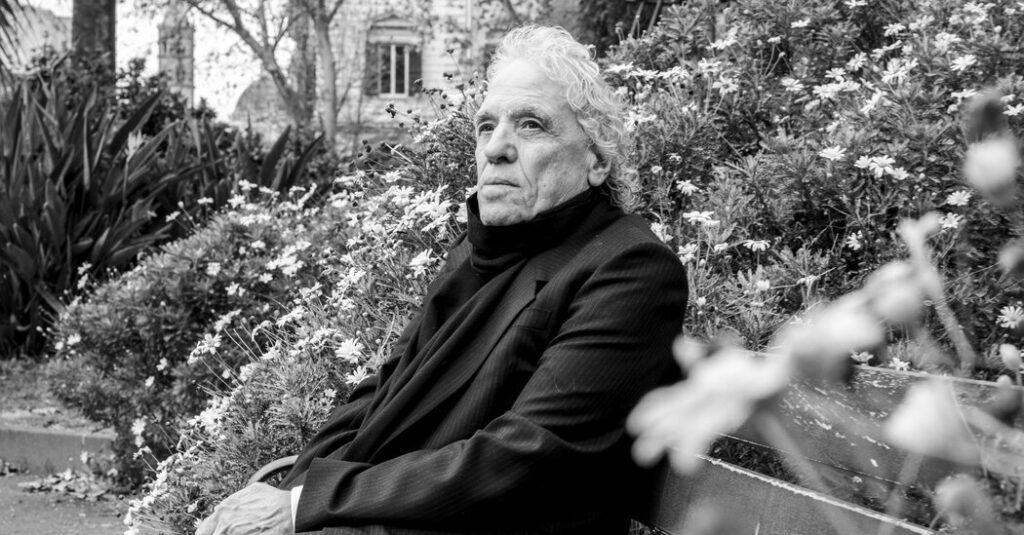

On a wintry afternoon in Rome, the film director Abel Ferrara stepped into an old trattoria not far from his apartment. He was wearing a black hoodie under a denim jacket. Beneath the arched ceiling, he slouched into a straw chair.

The restaurant wasn’t yet open, but a waiter deferentially took his order — eggplant parmigiana and a bottle of mineral water. Once the meal arrived, the white-maned owner approached the table to make sure everything was all right. It was.

“Here, they call me ‘maestro,’” Mr. Ferrara, 74, said. “They know I’m a filmmaker. That’s special to them. In New York, who cares? All you’re doing there is killing yourself to keep a roof over your head.”

“What is my fame?” he mused. “Who knows. I’m famous enough, ya dig what I mean? Am I Marty Scorsese? No.”

Despite his stature as a folk hero of New York independent film, enshrined in the city’s cinematic canon for gritty classics like “King of New York,” “Bad Lieutenant” and “Ms .45,” the Bronx-born director has been living in Rome for over a decade.

His cultish fans revel in the ways his films capture a bygone, sleazy New York, a city where it was easier to score heroin than a matcha latte. In “Bad Lieutenant,” which shocked audiences at Cannes in 1992 on its way to receiving an NC-17 rating, Harvey Keitel played a junkie cop who finds redemption while investigating the rape of a nun.

“King of New York,” a gangster epic starring Christopher Walken as a drug lord, “made ‘Scarface’ look like ‘Mary Poppins,’” as Mr. Ferrara once described it. In an early film, “The Driller Killer,” Mr. Ferrara not only directed but played the lead: a downtown artist who embarks on a murder spree with a power drill.

Ever since he traded the grimy chaos of Manhattan for the more affordable chaos of Rome, Mr. Ferrara has been making movies in Italy with the same guerrilla energy he possessed as a grindhouse auteur who produced his projects with help from mobsters and shot on location without permits.

We met at the sleepy trattoria to discuss his recently published memoir, the diaristic “Scene,” in which he details his up-and-down career and provides a harrowing account of the heroin addiction that was nearly his undoing.

If you haven’t heard of his recent films — like “Turn in the Wound,” a war documentary shot in Ukraine, or “Zeros and Ones,” a cryptic thriller set in Rome starring Ethan Hawke — that’s because many of his latest endeavors have encountered distribution problems. But for Mr. Ferrara, long a Hollywood outsider, the work is what matters, and he has found creative refuge from meddlesome film executives here in Italy, where the director’s vision is sacrosanct.

“I’m not making a movie unless I have final cut, ya dig?” he said in the trattoria. “I don’t have to battle for that here. There’s a place for art and culture. If you’re a director, you’re respected. If you’re an actor, you’re respected. It doesn’t matter if you haven’t worked for five years.”

He pointed to the waiter.

“Even him, he’s respected as a waiter. And this guy’s a great waiter. In New York, who are waiters? Pissed-off actors. And so the sacrament of the food, of eating, then becomes affected. Because they’re pissed off they got to wait on you.”

Mr. Ferrara took a swig of water.

“I drink a lot of water,” he said. “It replaces the alcohol.”

He got sober in 2012 at a rehab facility near Naples, not far from the village where his grandfather was born. In his memoir, he recounts how he snorted heroin one last time in a cafe bathroom before committing himself. “It all ends the same for every addict, in isolation,” Mr. Ferrara writes. “They call sobriety finding the self of your former ghost.”

He describes scoring crack and getting high until the early morning hours before showing up sleepless on the set of “Bad Lieutenant.” And when his wife and two daughters were evicted from their West Village apartment, he said his first instinct was to buy more drugs before hitting up Mr. Walken for a loan.

He writes of getting out of a drug possession bust because an arresting officer was familiar with “King of New York.” He tells of his affairs with actresses, including a chaotic fling with Asia Argento when he was making the 1998 film “New Rose Hotel.”

He also grapples with having grown up the son of an addict. His father, a gambler and bookmaker who owned several bars in the Bronx, tried to kill himself when Mr. Ferrara was a boy by downing a bottle of Seagram’s 7 with a fistful of pills; his father later died by suicide in 1980, he writes.

Mr. Ferrara’s memoir arrives at a moment when he’s experiencing a revival of sorts. He plays a vengeful gangster in “Marty Supreme,” a film directed by Josh Safdie, the co-director (with his brother Benny) of “Uncut Gems”; and Mr. Ferrara’s own hyper-violent and seedy classics have lately entered the rotation of the downtown Manhattan art-house cinemas Metrograph and the Roxy — though he desperately wishes his younger fans would check out his newer works like “Turn in the Wound” instead.

“When they talk about those films as if they’re the only movies I made, it bores me,” Mr. Ferrara said, referring to “Bad Lieutenant” and “King of New York.”

Joining Mr. Ferrara halfway through lunch was the 37-year-old actress Cristina Chiriac, who ordered a plate of cacio e pepe. They became romantically involved when she appeared in his 2014 film “Pasolini,” about the final days of the Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini, then became domestic partners. They are now separated, but remain on friendly terms, working together to raise their daughter, Anna.

“My daughter is 10, and she’s trying to sneak-read my book,” Mr. Ferrara said.

“I haven’t read it yet,” Ms. Chiriac said. “I’ll read it when the moment feels right. But I don’t think there’s anything in there that will surprise me. We’ve been through a lot together. I already know about his life.”

The conversation turned to Mr. Ferrara’s role in the buzziest movie of the season.

“I haven’t seen ‘Marty Supreme,’ and if I’m in it for two minutes, it would be a miracle,” he said. “But Josh is a brother in arms to me.”

“I met him when I was living on Mulberry Street and he was working in a little DVD rental store,” he continued. “He’s giving me the script of ‘Uncut Gems’ to show Harvey Keitel years before he and his brother made it. I always wanted to support them. But I was a junkie then. He knew that Abel.”

Calling Mr. Ferrara a “street poet” in a phone interview, Mr. Safdie recalled witnessing the harsher side of one of his cinematic heroes.

“There’s two Abels,” Mr. Safdie said. “There’s the Abel that existed in addiction, and there’s the Abel who exists in sobriety, and I knew both. When I worked at the video store, that he lived down the block from, he was a Tasmanian devil. He’d come in. He’d cause problems. He’d be in a bad way. But then he’d show up on Sunday with a DVD rough cut of ‘Go Go Tales’ and show it to us.” He added: “We’d see this Jekyll and Hyde.”

Mr. Safdie said he had always had Mr. Ferrara in mind for the role of the gangster, named Ezra Mishkin, in “Marty Supreme.”

“Ezra Mishkin is a bad dude, but he’s also sensitive, and he loves his dog,” he said. “The second you see Abel enter the movie with his dog, the dog softens him in some ways. But there’s a hardness to him. You can feel the entire memoir in his face.”

Three years before Mr. Ferrara started writing his memoir, he directed “Tommaso,” a deeply personal movie set in Rome. In it, Willem Dafoe plays a director who has moved to Italy and embraces sobriety. The film depicts him in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings recounting his New York past while trying to raise a daughter with a young wife. Those roles were played by Ms. Chiriac and Anna.

“Abel is the same guy before as he is now, particularly creatively,” Mr. Dafoe said in an interview. “It’s just you’ve taken away that devotion to something that has been destructive in his life.”

“Now, that devotion to his addiction has been replaced by something different, and it’s not as neat as some sort of redemption or contriteness,” he added. “But it does have to do with leading a life that contributes something that he thinks will get him to some sort of truth.

“He is dear to me,” Mr. Dafoe said. “But he is also flawed.”

In a small bar, the Brick Space, on Piazza Vittorio one cold night, Mr. Ferrara stood, eyes closed, strumming an acoustic guitar and singing Bob Dylan’s “Blind Willie McTell.” His voice was rough, with an ache to it.

The room was filled with old friends and members of his Italian cinematic family. Ms. Argento, a Rome native who remains close with Mr. Ferrara since their long-ago affair, tapped her knee-high black boots in rhythm with the song.

After the performance, Mr. Ferrara drank from a bottle of water he clutched by the neck. He doted on Anna, who sat beside Ms. Chiriac.

“Doesn’t she have to go to school tomorrow?” Mr. Ferrara said. “She never wants to go home.”

The gathering spilled outside, into the piazza’s porticoes, where people smoked cigarettes as they discussed the next Ferrara production, “American Nails,” a modern gangster retelling of the Greek tragedy of Phaedra that is scheduled to start filming soon in Bari.

Mr. Ferrara seemed in his element. “This is how I make movies, always hanging out with my guys — except back then, half these people would be drug dealers, and we’d all be sitting here doing coke,” he said. “I wouldn’t be worrying about where my kid is.”

“I don’t miss any of it,” he added. “I can make movies without being high — that’s the revelation. You think you need something, but the power of it is the delusion.”

He walked off into the night with his girlfriend, Johanna Adde-Dahl, a young Swedish actress who had sung at the bar just after his set.

Ms. Argento, who is set to star as Phaedra in “American Nails,” was hanging out in the galleria, without a drink in hand.

“I’ve known Abel more than half of my life, and I was 22 when we met in New York,” Ms. Argento said. “I don’t exactly remember it all, because we were also very high, but we went from the darkness to the light together.”

“You think people don’t change, but Abel changed,” she added. “I’ve been sober for almost five years thanks to him.”

“He cannot speak Italian, but he’s one of us now,” she said. “I think the New York he once made movies in, a New York that was dirty, scary and dangerous, but also artistic, doesn’t exist anymore. Now it’s all money oriented. I think Abel has found in Rome what he was once finding in New York.”

Mr. Ferrara still has his tortured and bellicose moments. “It’s a dark side of my nature, the addict side,” he said of his stormy temperament. “Even 13 years in, even with the meditation, it’s still one day at a time.”

When he introduced me to Mr. Dafoe via email, but I failed to quickly reply because I was on a trans-Atlantic flight, he called me in a rage, hurling into a profanity-laced screed so searing that it stunned me. He texted an hour later: “sorry for my outburst, as usual uncalled for.”

I got another glimpse of his more lashing side after we had pleasantly played blues guitar together for a while in his small apartment overlooking Piazza Vittorio. When I asked him what he hoped readers might take away from his memoir, he roared: “Why do you always go there with these stupid questions?”

Soon enough, he was pacing about the room, delivering his thoughts with a street preacher’s passion. A stuffed Buddha plushie sat atop a speaker on his film editing bay near shelves cluttered with books about Pasolini and Dylan. He vented that journalists keep harping on his early work, though he’s an active artist still shedding his blood on the celluloid frame.

He finally sat still when I asked about the passages in his book regarding his first family in New York.

“I had two daughters — I went through it high, and I failed them,” he said. “One I’ve made amends to, and we’re getting there. The other does not speak to me. And I respect that.”

Mr. Ferrara said: “I don’t want to fail Anna.”

“I want her to get the truth,” he added. “When she’s old enough, she can read my book, and she’ll take it or leave it. I only hope it doesn’t romanticize the drug use.”

Anna lives with her mother in a grand stone-floored apartment nearby. After he and Ms. Chiriac split up, he left them the apartment and rented the smaller place near the park.

I tagged along with him one afternoon when he paid a visit to see Anna after school. She was practicing the harp in the living room, plucking out the theme from “Beauty and the Beast.” She told me she hoped to see “The Driller Killer” when she’s 18. And she said of her father: “Sometimes he gets angry, but the truth is he’s sweet.”

Her mother looked on as she resumed practicing.

“She gets emotional, because she loves him a lot,” Ms. Chiriac said. “She sees him, and she understands him.”

“For him, Anna has been another chance,” she added.

The next evening, Mr. Ferrara was back, this time to run an errand with Anna. It was getting dark and a hard rain began to fall when we left the building. He trudged through the downpour, wearing his black hoodie under his denim jacket. Anna walked a few steps behind him, carrying a green umbrella. When they crossed the street, he shot a glare at a car that got too close.

We neared the glowing light of a shop. Anna ran inside.

“This is the most important store in Rome,” Mr. Ferrara said. “She has everything she needs here for school.”

Deep in the aisles, Anna looked through the bright binders and colorful markers. Then she raced back to meet her father at the register, carrying a spiral-bound diary and a glittery key chain.

“Let me carry that,” he said as they left. “And tie your shoe. Don’t step into the puddles.”

They walked back home together, Mr. Ferrara leading his daughter through the rain.

Alex Vadukul is a features writer for the Styles section of The Times, specializing in stories about New York City.

The post In Rome, They Call Him ‘Maestro’ appeared first on New York Times.