In college in Washington, D.C., I always told people I grew up outside of Los Angeles. Pressed further, I’d say near Pasadena.

I rarely told people I was from a small town called Altadena.

There was no easy way to describe my hometown. It didn’t fit any of the expectations of Southern California. It wasn’t a tourist destination like Hollywood, or glamorous like Beverly Hills, or beachy like Malibu or Venice. We didn’t have our own lingo and mall culture, like they did in the Valley. We didn’t have the Rose Bowl or a world-famous parade like Pasadena. Even the meaning of Altadena’s name was tied to the history of the city it rested against.

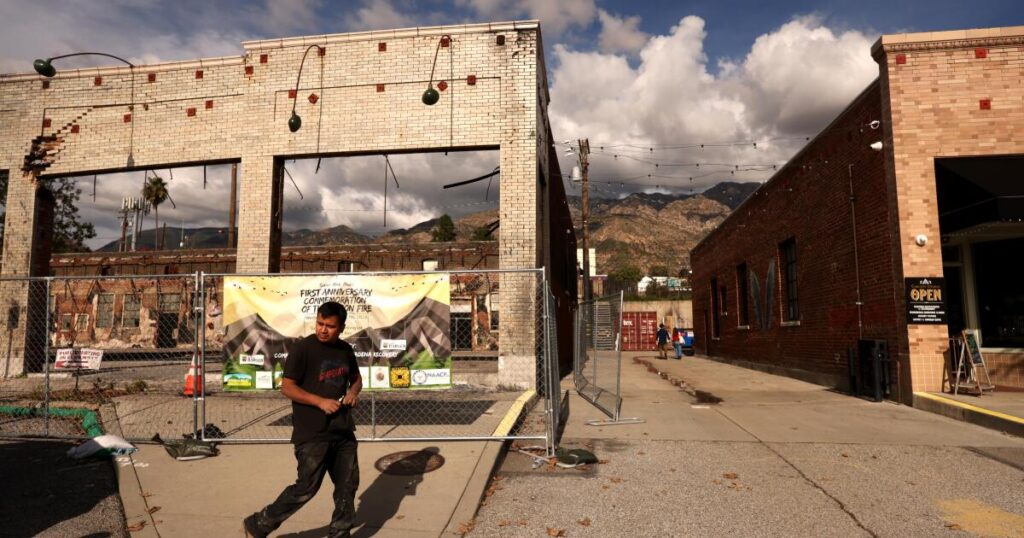

Then Altadena burned.

The inferno took the lives of at least 19, jumping east to west and burning 9,000 homes, businesses and other structures to the ground.

The town’s moment in the spotlight was its destruction.

I wish I had told people before about my Altadena, a place I didn’t realize how much I loved until it was gone.

The town I grew up in was in many ways quintessential California: one of the many harbors in the urban sprawl where people from all over the U.S. and the world quietly settled and built a space with its own unique and complex personality.

Altadena was where people raised chickens before it was trendy, where no one batted an eye at the neighbors with a pet dingo, or thought much about the so-called haunted road said to defy gravity. Some people lived off the grid up against the mountains and used their own generators for electricity. Others were engineers at the Jet Propulsion Lab and professors at Caltech and teachers and artists and plumbers and everyday commuters to downtown Los Angeles.

You could be whoever you wanted to be here — as eccentric or conventional, ambitious or laid back as you wished. Multigenerational families from the Midwest planted early roots and never expected to leave. Black families migrated from the Jim Crow South and South L.A.; immigrant families came from the Middle East, Latin America, Europe and Asia.

This was the place where families could raise their children in peace under the deodar cedars and watch the San Gabriels fade to a distinct purple as the sun set. Where they could hike Eaton Canyon to the waterfall and stroll with their children down Christmas Tree Lane during the holidays.

A year after the fire, my mind whirls between nostalgia and today’s reality, where I’ve straddled the roles of reporter and heartbroken Altadenan. Like so many, I’m still grappling with what happened here.

::

My mom was the first to tell me.

From inside the house where I grew up, where she had also been raised, she smelled smoke. The sky glowed orange.

“Do you know what’s happening?” she asked me over the phone. I live 15 minutes away from Altadena and had no idea that a fire had just erupted.

In the decades that my mom has lived in the town, this was closer than most previous fires in the area, which typically started farther north and deeper in the mountains. The Eaton fire took off less than two miles east from my family’s home, not far from the base of Eaton Canyon.

My Italian great-grandmother moved into the English Tudor in the 1940s on a street lined by deodars and palm trees.

She and her husband, an Italian immigrant, raised their four children in Utah. Later, when the kids were adults, the family uprooted to California.

It was my late grandmother and my late great-aunt who found the house in Altadena, but no one knows exactly why they settled there. It’s become a great mystery for me this past year as I’ve asked so many residents why they chose this place. I have theories — that its closeness to nature reminded them of the rural areas they were used to; that the quiet was less overwhelming than other parts of the Los Angeles region; that the housing prices were more affordable than in other cities.

After my mom’s father died when she was young, she and her sister were raised there by their mother and aunt, who taught at the nearby elementary schools, and my great-grandmother, whose homemade bread and spaghetti and meatballs filled the kitchen and whose basement was stocked with fruit preserves from the apricot, fig and peach trees in the backyard.

The house was the center of some of my first memories: hiding behind the living room window curtain to play hide-and-seek, tumbling outside in the grass and looking up to see the mountain peaks in the distance; running through my great-grandmother’s garden.

My mom, dad, newborn sister and I moved into the home after my great-grandmother died.

::

My family evacuated about an hour after my mom called. It took them 30 minutes to drive 10 blocks as others poured out from the area, navigating downed power lines and trees.

At midnight, I got a text message from one of my best friends who grew up a few blocks north of me. Her cherished home, where we’d held so many joint birthday parties, was gone. My mind could not grasp it. As the winds picked up, I braced myself for what was to come.

The next morning, I had to start reporting.

I stopped first at the Pasadena Convention Center to prepare myself for what I would find. There, people recounted their harrowing evacuation stories, unsure of whether their home survived, unsure of when or if they’d be able to return.

Then I drove north into Altadena.

I found my family’s house still standing. Relief washed over me as I called my mom with the news. Though some properties were lost, our street was largely spared. The theory is that the fire couldn’t breach the open space of the public golf course that stood a few blocks north.

But just two blocks up from my family’s house, the fire ravaged the town. I drove through the neighborhoods in a daze, bewildered by what I saw.

On blocks I rode my bike all over and trick-or-treated on, where I played tag and Red Rover with friends, where my family would drive around looking for our border collie who regularly jumped out of our yard to explore the neighborhood, homes were still on fire.

The winds had died down but threatened to pick up again. Homes that had caught on fire in the early morning hours were still up in flames. Residents who had evacuated, and some who had stayed behind, stood shell-shocked, knowing there was little they could do to stop their neighborhood from burning to the ground.

Firetrucks hurtled by, forgoing those burning homes believed to be lost causes. One woman clutched her cheek and smoked a cigarette as she watched the house across from her burn to the ground; neighbors passed buckets of water back and forth to try to save what they could. But all around, so much had already been destroyed. I stood with one family as they watched their home burn, unable to do anything. They’d left with only their pajamas, sure they’d be returning soon.

Everyone I met then and in the months since believed the same thing; that after evacuating, they would be back. That the fire wouldn’t jump as far south as it did. That Altadena would be safe.

No matter how many times I’ve driven these streets this past year, I am still taken by surprise. Probably, one resident told me, because our brains haven’t had time to rewire themselves from the expectation of what we’re used to.

I still expect to find the Altadena I knew for so long.

On some blocks, I can close my eyes and picture how it was before. Trudging behind my mom to the local nursery, winding through the stacks of pansies and roses. Having coffee at my sister’s favorite coffee shop, Cafe de Leche, and picking up burgers in the summer with my dad from one of his favorite spots, Everest. Admiring the stationery and figurines at the original Webster’s Pharmacy and gawking at the endless array of birds at Steve’s Pets shop.

Sitting in my car under my favorite oak tree when I’d had a rough day. The branches dipped low, ensconcing me with the solace I needed.

My husband grew up 10 blocks away from me. His family’s neighborhood was spared, but he and his sister lost their beloved elementary school. Family friends on both sides who months before had been dancing at our wedding lost their homes or found themselves displaced. Change in routine and care exacerbated underlying health conditions and at least two people we knew, including my late grandfather’s last living sibling, died after the evacuation. It affected our family dog too, who we said goodbye to after nearly 16 years.

My own family remained evacuated at a hotel in Glendale as they awaited remediation to clear the space of ash. My mom got in the habit of asking people if they were there for “vacation or evacuation.” The majority of the time, it was the latter.

In the lobby of their hotel, the evacuees would gather for happy hours. Some hoped to get back after smoke remediation; others had lost everything. They recounted their stories about life before, taking comfort in a forged solidarity that can only come with shared trauma.

My family was lucky in so many ways. Our house was still there. Our neighbors’ homes made it too. If you drove to the street, you could almost pretend everything was the same as before.

During those first months after the fire, the street was eerily empty except for the National Guard, which took position for weeks on the north side below the burn zone. After reporting assignments interviewing residents who lost everything or couldn’t get back to their homes to assess the damage, I’d often file feeds while parked in the driveway of my childhood home. Then I’d sit on the porch and cry over what I’d heard and seen, over what had become of my town.

I met so many residents who had lost their entire worlds. Their family photos, kids’ artwork and stuffed animals, their vinyl collections and cars, their tight-knit neighborhoods, their forever homes. Families who had lived in Altadena for generations lost the keepsakes and records of their entire history; some lost neighbors or family who didn’t make it out.

Amid their grief over unimaginable loss, at town halls, in churches, at community gatherings and outside the remnants of their homes, resilience was present too. Their stories have stuck with me:

The woman whose late grandfather built the house she grew up in, the same house where her mother was raised in west Altadena. She searched among the rubble for some memory of him, finding a ceramic bear he had gifted her years before that bore the message “I love you.”

The business owner on North Lake Avenue who opened her restaurant on Cinco de Mayo to offer the community an ounce of normalcy. A mariachi band played as she danced in the middle and reunited with longtime customers.

The group of women who lost their own homes and, in the aftermath, canvassed neighborhoods to prevent healthy trees from being mistakenly chopped down; the immigrant workers in hazmat suits who cleared homes of ash as immigration raids escalated; the Altadenans who rose up as community advocates to fight for a better settlement from Southern California Edison and empower their neighbors to rebuild.

In the spring and summer, flowers bloomed throughout the town. On properties where no house was left, roses sprang to life and trees that had been charred started leafing again. Hope was not lost yet.

But in the months since, reality has become harder for many to cope with. For-sale signs continue to appear and questions over what toxic substances remain in the soil and whether it’s safe to return to the burned areas loom.

As the holidays picked up and as the one-year anniversary of the fire approached, many I’ve talked with are struggling more now than at the beginning when adrenaline fueled the momentum of daily survival.

At first, there was no time to grieve all that was lost.

::

Months after the fire, my family was able to move back to Altadena. The streets were quieter and any fanfare gave way to new uncertainty over what obstacles might emerge and a fear that what took place last January could happen again.

But in the doorway of my childhood home, I was able to tell my mom that I was pregnant with my parents’ first grandchild.

My daughter is due in the coming weeks.

On a recent winter night, I walked the stretch of Christmas Tree Lane past lit-up signs that memorialized Altadena’s unbreakable spirit. As I cradled my belly, I saw a message of strength: “Altadena, our roots remain.”

In time, she will know what happened here. She will know about the destruction, she will know about the pain. But she will also know about the bravery, the resilience; what this place was and what it will become.

One day, she will know this story. Altadena’s history is hers too.

The post A year after the Eaton fire, the loss of Altadena is still raw appeared first on Los Angeles Times.