As independent journalism comes under increasing threat worldwide, a trio of Oscar-shortlisted documentaries offer revealing perspectives on risk-taking reportage that challenges institutional power with hard and often shocking facts.

At five-plus hours, Julia Loktev’s “My Undesirable Friends: Part 1 — Last Air in Moscow” examines in depth a group of young female journalists countering state propaganda in Russia, even as they are systematically targeted by the government in the months before the country’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. “Cover-Up,” directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, focuses on the career of a single investigative journalist, Seymour Hersh, whose decades of exposés include his 1969 report on the My Lai massacre and his discovery of the American torture of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib. And in “The Alabama Solution,” filmmakers Andrew Jarecki and Charlotte Kaufman investigate systemic abuse inside the Alabama state prison network, collaborating with inmates equipped with smuggled cellphones.

When Russian-born American filmmaker Loktev began shooting “My Undesirable Friends” in 2021, she didn’t imagine how its subjects’ struggle would anticipate autocratic pressure on the free press in the United States.

“I wasn’t making it for Trump’s America,” she says. “I was making it in somewhat reasonable Biden’s America. But so many things in the film that seemed like they were in a place far away started to have resonance.” Loktev shot the film on an iPhone, which evokes a casual, intimate vibe — at least until the story accelerates into a thriller. “It’s not really fly-on-the-wall, it’s fly-on-your-nose,” she quips. The journalists, who write and produce news for the independent outlet TV Rain, are first branded as foreign agents, then forced to flee the country as the war begins.

“I opened up the newspaper last night and started reading about the ‘60 Minutes’ piece,” she says, referring to CBS editor in chief Bari Weiss’ controversial decision last month to stop the airing of the newsmagazine’s report on the CECOT maximum-security prison in El Salvador, where the United States has sent deported Venezuelan and Salvadoran migrants. “Russia also didn’t start by jailing journalists. They started by suing journalists, by using economic means to shut down journalism …. Where it goes, we don’t know, but it is something that is feeling increasingly familiar.”

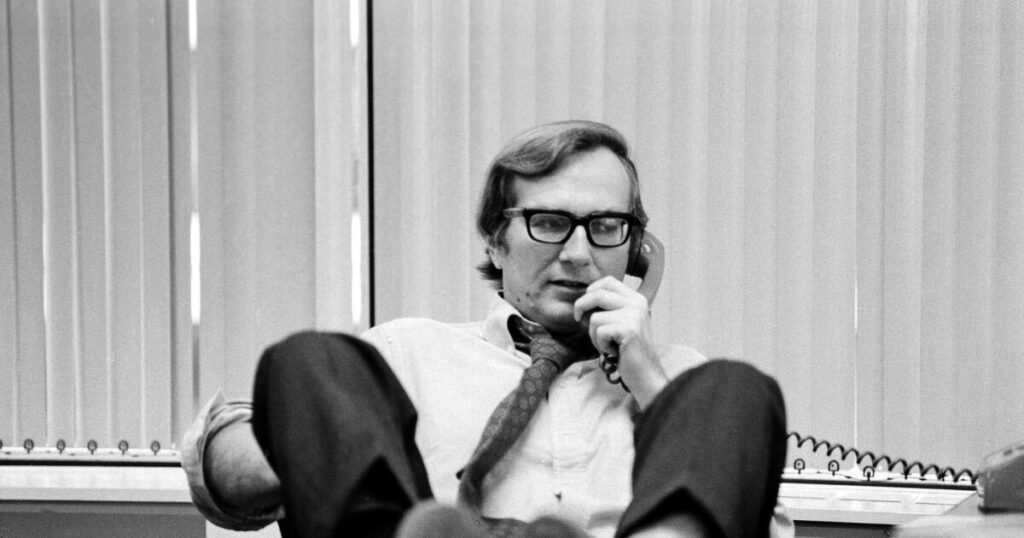

Now 88 years old and still on the beat, Hersh, the Pulitzer Prize-winning subject of “Cover-Up,” has battled the establishment since he began his career. And not just political leaders like disgraced President Nixon, whose 1974 exit from office was likely hastened by Hersh’s coverage of the Watergate scandal, and whose famous assessment of the journalist the documentary revisits: “I mean, the son-of-a-b— is a son-of-a-b—, but he’s usually right, isn’t he?”

“The film has several themes, one of them being government atrocities and lies and cover-ups and impunity,” says Poitras, who won an Oscar in 2015 for “Citizenfour,” her portrait of National Security Administration whistleblower Edward Snowden. “But another one is journalism and institutions not publishing stories that are clearly newsworthy, that look badly or reflect negatively on this country.”

The film offers an example in detailing how Hersh fought to get his breakthrough My Lai story into print. “He went to Life magazine, and they said no at first,” Poitras adds. “Only later did they publish the story when the photos came out.” Hersh’s recourse was to syndicate the piece through the independent Dispatch News Service, run by his literary agent David Obst. “It became the biggest story around the world, but that took time,” Poitras notes. “It says something about the media that it continues to today, across every administration.”

Six years in the making, “The Alabama Solution” is an unsparing indictment of inhumanity and dysfunction in the state’s prison system, where more than 1,300 deaths have been reported since 2019. The point of view belongs to a group of inmate activists, who document abuses on contraband cellphones.

“Independent journalism, free of government oversight, is something we all have accepted as a core democratic principle,” says Kaufman, who directed with Jarecki, a 2004 Academy Award winner for “Capturing the Friedmans.” “But when it comes to prisons, we have historically surrendered that principle … we are fine allowing the government-approved narrative.”

As seen in the documentary’s opening scenes, the project began after the filmmakers were invited to film a barbecue at the Easterling Correctional Facility, one of 14 prisons in the system. They were approached by prisoners who told them disturbing things. “They said, ‘You need to look more deeply into this.’ They were quite specific,” Jarecki says. The goal was “to see if it was possible to make a film that was coming directly from the men inside.”

The four men who became the film’s principal subjects had been using the cellphones for several years as they fought to bring attention to their plight. “They took great risk in speaking with us, and in participating in this film,” Kaufman says. “They did that because they truly believe in the power of the Fourth Estate. When they felt that the state had failed them … when they felt like the courts had failed them, when they felt like even the federal government had failed them … they turn to the court of public opinion. They turn to journalism.”

The post Inside 3 Oscar-shortlisted docs that highlight the power of the exposé appeared first on Los Angeles Times.