Delcy Rodríguez, the new leader of Venezuela, is in a tough spot. She has to contend with the coercive demands of the U.S. government, which just seized her predecessor. But she also has to maintain the loyalty of her country’s ruling elites.

After a U.S. military operation captured President Nicolás Maduro and flew him to New York to stand trial on drug charges, President Trump indicated that the United States would allow Mr. Maduro’s inner circle to retain their hold on power as long as they satisfied the U.S.’ foreign-policy demands.

That leaves an explicit threat hanging over the head of Ms. Rodríguez, who was sworn in as acting president. The U.S. military, still stationed off Venezuela’s coast, has shown that it can easily penetrate the country’s defenses. But Ms. Rodríguez must also maintain the loyalty of Venezuela’s ruling elite after an extreme and sudden disruption of the status quo — a moment that political scientists have long recognized as perilous for leaders.

Making matters even more complicated, Venezuela’s populist ruling ideology — known as “Chavismo” after the former president Hugo Chavez — was based in large part on opposition to American imperialism.

No leader governs alone

Political scientists say the outcomes of political crises like these depend on whether a government’s coalition can remain united.

If leaders can convince enough crucial elites that loyalty is still the best way to promote their material interests and protect them from harm, then their coalitions can often hold, even in the face of coups, popular uprisings or foreign military incursions.

“Because of the resources and access that they have, elites pose the biggest threat to authoritarian leaders,” Erica de Bruin, a political scientist at Hamilton College who is the author of the book “How to Prevent Coups d’Etat: Counterbalancing and Regime Survival,” told me in 2022. “Retaining the support of elites is thus crucial to remaining in power.”

Venezuela’s 2024 presidential election, which Mr. Maduro lost by a landslide according to exit polls and outside observers, was a good example. Because the military and other elites remained loyal to him, he was able to hang on to the presidency despite losing the last shreds of electoral legitimacy.

But if elites believe a government can no longer protect their interests, or that a new leader could offer them a better deal, the coalition fractures. And if that happens, governments can suddenly collapse.

In Ukraine’s 2014 “Maidan revolution,” pro-democracy protests prompted the heads of the military and other security services to abandon President Viktor Yanukovych. Within hours, he had lost power and fled the capital. “The president was not so much overthrown as cast adrift by his own allies,” a 2015 Times investigation found.

In Venezuela, the government has long relied on an inner circle of powerful figures from politics, the military and other security services. Those elites have grown wealthy on the proceeds of corruption, including black-market oil sales and narco-trafficking. Many have longstanding ideological ties to Mr. Chavez and his socialist, anti-imperialist political project. But U.S. demands are likely to strike at the heart of both ideological and material interests.

Ideology vs profits

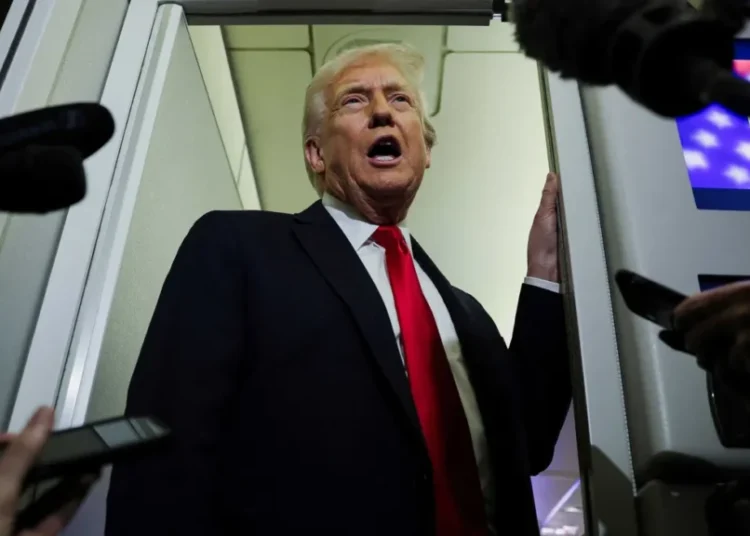

Cuba may become a focal point for ideological tensions between U.S. demands and those of Ms. Rodríguez’s coalition. Some within the Trump administration, particularly Secretary of State Marco Rubio, have long believed that cutting off Venezuela’s support would deal the Cuban government a critical blow. “Cuba looks like it is ready to fall,” Mr. Trump recently told reporters on Air Force One. “I don’t know if they’re going to hold out, but Cuba now has no income. They got all their income from Venezuela, from the Venezuelan oil.”

But the relationship between Cuba’s communist government and Venezuela’s Chavistas is deep and longstanding, said Leonardo Vivas, a lecturer in international politics at Emerson College. It has remained intact despite Venezuela’s chaotic flirtation with free markets in recent years. If Ms. Rodríguez cuts off support for Cuba at the behest of the United States, that would be a sharp break with what remains of Chavismo as an ideology.

Other demands may lead to more material conflicts. The Trump administration has accused Mr. Maduro of being a narco-trafficking leader, and bombed Venezuelan boats that it claims were bringing drugs to the United States. Many of those claims are dubious — Mr. Trump has claimed to be targeting deadly drugs like fentanyl, but Venezuela’s role in that trade is modest — experts say Venezuela is a transshipment point for cocaine, even if much of it is bound for Europe, not the United States.

The country’s politicians and military elite have long profited so much from Venezuela’s drug trade that Venezuelans jokingly call them the “Cartel de los Soles,” or “Cartel of the Suns” — a reference to the sun insignias that Venezuelan generals wear to denote their rank, similar to American generals’ stars. (Cartel de los Soles is not, despite the Trump administration’s claims, an actual cartel.)

Mr. Trump has also said the United States will profit from Venezuela’s vast oil reserves. Those oil revenues have long been a way for the Venezuelan government to buy loyalty, said Francisco Monaldi, the director of the Latin America Energy Program at Rice University’s Center for Energy Studies.

Before U.S. sanctions, payoffs were made through P.D.V.S.A., the national energy company. But after sanctions, “the mechanism to distribute money within the regime became the black market,” he said, “basically assigning tankers to certain favored people connected to the regime.”

The question, then, may be whether Ms. Rodríguez can satisfy the Trump administration’s demands while also compensating Venezuela’s elites for the loss of any black-market profits.

“They have to restructure all the architecture of how they distribute the spoils,” Mr. Monaldi said. “At this point, it’s very much unclear how this will work out.”

Amanda Taub writes the Interpreter, an explanatory column and newsletter about world events. She is based in London.

The post Can VenezuelaNew Leader Keep the U.S. Happy and Her Elites in Line? appeared first on New York Times.