THIS IS WHERE THE SERPENT LIVES, by Daniyal Mueenuddin

“The relation between the chauffeur and the chauffeured can be curiously intense,” Iris Murdoch wrote in “The Sea, the Sea.” This was true in David Szalay’s Booker Prize-winning novel “Flesh” (2025) and also in Daniyal Mueenuddin’s sensitive and powerful first novel, “This Is Where the Serpent Lives,” set largely in rural Pakistan.

If Mueenuddin’s name sounds familiar, it’s because his first book, a collection of stories titled “In Other Rooms, Other Wonders” (2009) was a finalist for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. Its title echoed Truman Capote’s “Other Voices, Other Rooms” and its prose echoed Anton Chekhov’s in its spareness and sometimes oppressive sense that no hair was out of place. “I am constantly reading Chekhov,” Mueenuddin said in an interview. “I am never not reading Chekhov.”

His novel, like his stories, has at its center the workings of an old and teeming Pakistani farm, where castes and ambitions collide. To recall Big Daddy Pollitt’s line in Tennessee Williams’s “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” there’s an odor of mendacity around the plantation. Everyone is jostling for favor as the old feudal system gives way — for love, dignity, extra chapatis, a new iPhone, a floor to sleep on, an escape to Cambridge (either one) for an elite education, a less thorough torturing by the corrupt rural police.

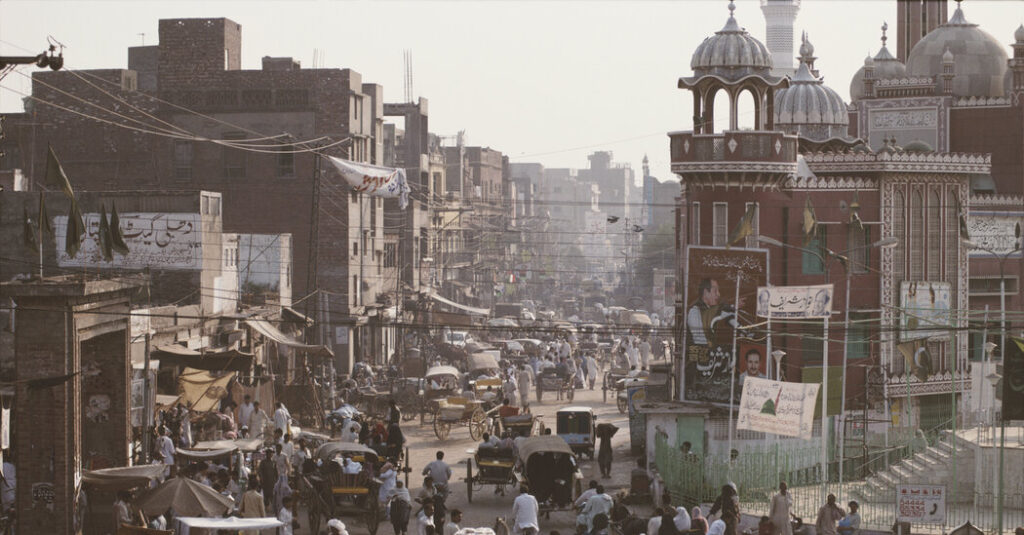

Mueenuddin knows this material. For several decades he’s lived on a farm in Pakistan’s South Punjab. He divides his time between it, his dust jacket tells us, and Oslo. This is not a typical farmer’s commute. The son of a prominent Pakistani diplomat, Mueenuddin grew up in Lahore and in Wisconsin before graduating from Dartmouth and Yale Law School, then worked for several years as a corporate lawyer for Debevoise & Plimpton in New York City.

Some writers appear to listen when their parents order them to have a backup plan.

“This Is Where the Serpent Lives” is related in four linked, carefully controlled stories that play out across decades. Phrases like “linked stories” and “across decades” have been known to dampen enthusiasm among certain easily irritable readers. So do lists of “principal characters” up front, as this book has, and august but bland titles, as this has as well. But right off the bat, Mueenuddin hands us a live wire.

He’s Yazid, the chauffeur, whom we first meet as an orphan in 1955 in a bazaar in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. He’s barefoot, alert, a nervy pipsqueak out of Dickens, at the bottom of the social pile. He manages to apprentice himself to the illiterate owner of a tea and curry stall, and he prospers.

He’s ambitious, Yazid, and he’s wild. He quickly learns to read. He’s canny and jolly and a Falstaffian storyteller — he makes a lot of friends as he ages, even among the local elite. He’s a big guy who lumbers around like a bear. By middle age, when he is the driver for a farm owner from Lahore, he appears to resemble Oscar Zeta Acosta, or Alfred Molina in “Boogie Nights”:

Tired at dusk, they drove in silence but for the music, Yazid intent on the road in front, his large face, long hair, drooping mustache and sideburns like a villain in a Punjabi film. This was his bread and butter, driving well, driving fast.

I kept wanting Yazid to overspill the banks of this novel, but Mueenuddin keeps him tucked in. He becomes a bridge that connects several of the other primary characters, including Hisham, for whom he drives, and Saqib, an ambitious young servant whose ferrety plans get out of hand. The women in “This Is Where the Serpent Lives” are sharply drawn, but their roles are more circumscribed.

Hisham graduated from Dartmouth in the 1970s; he was vice president of one of the fraternities that inspired the movie “Animal House.” He and his quieter brother, Nessim, who also attended Dartmouth, grew up with Yazid. He was their servant but also their closest companion; he helped raise them. Now Hisham has broken with his brother — he stole Nessim’s girlfriend — and has moved back to Pakistan with that woman, Shahnaz, who is now his wife.

The elite grow up listening to Radio Pakistan and the BBC Urdu service. They drop observations such as, “Dear dirty Pakistani International Airlines, there’s a metaphor for the Pakistani soul. Won’t fly, don’t fly.” They sense, with mixed emotions, the lingering effects of British rule.

“In Pakistan, every problem is a lock, and to that lock there is a single key,” Hisham says. I don’t think Mueenuddin believes this. By this novel’s lights, unless you are from the kind of family that can fix things with a single telephone call, every lock seems to have about 300 keys, most of which need extended jiggling.

The magic in “This Is Where the Serpent Lives” is the up-close work. Mueenuddin makes the reader care about the romantic relationships, and the pages turn themselves. He charts, with some amusement, the inroads that social media has made into ancient courtship rituals. Cellphones! They’re dispensers of Western pornography, too, of the sort that blows young Pakistani men’s minds.

Now the young men could sit in hidden places and see astonishing pictures, of women whose shamelessness seemed inconceivable. All of them wanted this, more than a motorcycle, more than any other luxury.

In his novel “Moth Smoke” (2000), Mohsin Hamid had a character say that there are essentially two social classes in Pakistan — the cooled and the uncooled, that is, those who are comforted by air conditioning and those who are not. Beneath that, the distinctions are myriad.

Like Hamid, Mueenuddin has an exacting sense of social hierarchy, especially of dignity on its last legs, and the multiple meanings of a glance, a touch, a vocal inflection, a phone call not placed. Pakistani society has grown more fluid, but not as much as many of these characters might wish.

About life on the farm, Mueenuddin writes, “This system did not just tolerate theft on a small scale but assumed it.” In the book’s last section, the servant Saqib, who works under Yazid, tests this system, with memorable results that I do not want to give away here. If he’s misjudged his plan, he’ll be stomped like a bug on a kitchen tile.

“This Is Where the Serpent Lives” is a more mature work than Mueenuddin’s stories. It’s a serious book that you’ll be hearing about again, later in the year, when the shortlists for the big literary prizes are announced.

I wish it were more unbuttoned. Mueenuddin, like a brilliant apprentice, has come to sound like the Russians (Chekhov, Gogol, Turgenev), with all their steadiness and focus and lucidity. But is it possible he has chosen mastery over genius? I wondered, just often enough, what his own voice might sound like.

THIS IS WHERE THE SERPENT LIVES | By Daniyal Mueenuddin | Knopf | 343 pp. | $29

Dwight Garner has been a book critic for The Times since 2008, and before that was an editor at the Book Review for a decade.

The post What if Chekhov Had Lived in Pakistan? appeared first on New York Times.