Venezuela’s oil reserves, thought to be the largest in the world at an estimated 300 billion barrels, are notable not just for scale. Most of the oil found there is among the dirtiest type, with high sulfur and low hydrogen content.

Before Venezuela plunged into an economic crisis under President Nicolás Maduro, the country was producing about 3.5 million barrels a day. Now it produces less than 1 million barrels daily.

Experts say it could take many years and billions of dollars of investment before the country’s production rebounds to earlier levels. In the meantime, the country is vulnerable to oil spills, it has one of the fastest deforestation rates in the tropics and the production of its oil generates more planet-warming greenhouse gases than most other types of crude oil.

Here are three things to know:

The ‘dirtiest’ oil

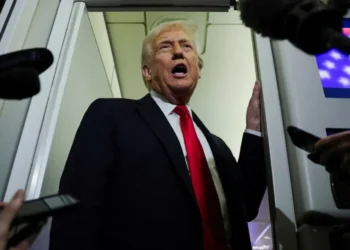

President Trump has described Venezuelan oil as “probably the dirtiest in the world.” When it comes to climate-warming pollution, that’s true.

Most of the country’s reserves are concentrated in the Orinoco Belt, a vast region in the eastern part of Venezuela that covers some 20,000 square miles.

“Most Venezuelan oil is what we call extra-heavy oil,” that is viscous and thick and has a higher sulfur as well as a higher carbon content than conventional crude, said Clayton Seigle, a senior fellow in the energy and geopolitics program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington research organization.

Because it is cumbersome to work with, extracting it is more difficult and more expensive than conventional crude, he said. It’s also more energy intensive to extract, generating far more carbon dioxide emissions than lighter oils. Like Canada’s bitumen-heavy oil, unlocking more of Venezuela’s oil will require advanced extraction technologies like steam injection.

Venezuela is currently responsible for less than 0.4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. But studies have shown that the production of heavy oils, including those from Venezuela, can generate three to four times as much greenhouse gas than the production of conventional oil.

An ‘insane’ amount of flaring

Methane, the main component in natural gas, is a potent greenhouse gas that leaks from oil and gas operations. It is also intentionally released at refineries, along with carbon dioxide, in a process known as flaring.

Despite the decline of Venezuela’s oil industry since the 1990s, its gas flaring has increased sharply, making it one of the world’s largest contributors to climate-warming methane emissions.

Methane traps about 80 times as much heat in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide in the short term and is responsible for nearly a third of the rise in global temperatures since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Gas flaring has been used in Venezuela for decades, but over the past decades corruption, mismanagement and insufficient infrastructure has led the country to burn off even more gas instead of collecting and utilizing it.

In 2023, Venezuela was the fifth-largest flaring country in the world, according to the Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report produced by the World Bank. Last year Venezuela released more than 40 percent of its gas, “an insane number,” said Jason Bordoff, founding director of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

Mr. Bordoff said a democratically elected government in Venezuela that could attract international investment could benefit the climate.

“Venezuelan oil is always going to be higher carbon content, but it could be much better than today,” Mr. Bordoff said.

Spills and deforestation

Venezuela’s weakened oil industry has exacerbated serious environmental issues in the country.

Between 2010 and 2016, Venezuela’s state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela disclosed more than 46,000 oil spills.

One year later, the company announced that it would stop reporting spills altogether, but independent researchers continued to discover dozens each month that jeopardize Venezuela’s mangroves, corals and marine life. They appeared to increase in 2023 after the Biden administration briefly loosened oil sanctions ahead of the country’s elections in an effort to encourage free and fair voting. Sanctions were reinstated shortly after the 2024 election.

A 2022 report produced by the U.S. Agency for International Development found that many of Venezuela’s oil facilities are within 30 miles of protected areas and that oil spills have contaminated drinking water in some parts of the country. That report was taken offline this year after the Trump administration dismantled the agency.

Illegal mining has also led to rampant deforestation. According to the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Program, a nonprofit group, about 346,000 acres of primary forest in Venezuela were destroyed between 2016 and 2020.

Faced with declining oil revenues, the Maduro government turned to gold mining as a means to generate revenue, often ignoring the environmental effects.

“With the most accessible gold deposits already having been mined, operations have expanded into protected areas, causing massive deforestation — over 1,000 square miles — and significant other environmental damage and habitat loss to national parks in Venezuela and the wider Amazonian ecosystem,” according to a recent State Department report to Congress.

The report also found that mercury and other chemicals used in illicit mining were contaminating rivers, poisoning fish and damaging drinking water sources.

Brad Plumer contributed reporting.

Lisa Friedman is a Times reporter who writes about how governments are addressing climate change and the effects of those policies on communities.

The post Venezuela’s ‘Dirtiest’ Oil and the Environment: Three Things to Know appeared first on New York Times.