As we approach the 250th anniversary of our nation’s independence in 1776, the temptation rises to focus on the year’s military engagement — but its most significant events occurred off the battlefield. Rather than as just one colonial people’s fight for independence from imperial rule, American patriots saw the events of 1776 as a revolutionary struggle to establish a new type of government: rule by law, not by men — or, in the terms of that day, by constitutions, not kings.

“The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind,” Thomas Paine wrote in the introduction to “Common Sense,” the bestselling pamphlet published in January 1776 that transformed an armed rebellion for colonial rights into a global revolution for representative government. “The birthday of a new world is at hand.”

New nations frequently splinter off old ones and have done so since the dawn of history. Paine and other patriots did not view the American Revolution in such narrow terms. To them, it promised something new under the sun or, as Continental Congress Secretary Charles Thompson soon inscribed in Latin on the Great Seal of the United States under the year 1776, “Novus ordo seclorum,” or “A new order of the ages.”

This “new order” was not merely an independent nation but a different sort of state: a constitutional republic based on popular sovereignty and rule of law in a world dominated by monarchies, theocracies, dictatorships and other authoritarian regimes. “For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King,” Paine explained.

“It has been the will of heaven that we should be thrown into existence … when a coincidence of circumstances without example has afforded to thirteen colonies at one the opportunity of beginning government anew,” John Adams wrote in a widely circulated March 1776 letter that served as the guide for constitution-making in the states. These new state constitutions became the first written ones in history and, along with the Declaration of Independence, represented the greatest legacy of 1776.

“The happiness of the people, the great end of man, is the end of government,” Adams wrote in a sentence that gave the lie to the pretensions of monarchs and practices of tyrants. “Therefore, that form of government which will produce the greatest quantity of happiness is the best.” Republics do so because they represent the people, he declared.

For Adams, the foundation of a secure republic rested on a representative legislature. “Equal interests among the people should have equal interests in it,” he wrote in a warning against the malapportionment of electoral districts then common in England. “Great care should be taken to effect this and to prevent unfair, partial, and corrupt elections.”

To assure “strict justice” in all cases, Adams proposed a system of checks on power. An independent, elected, term-serving executive would administer laws passed by the legislature. Judges nominated by the executive and confirmed by legislators would possess judicial authority “distinct from both the legislative and executive, and independent upon both, that so it may be a check on both and both should be a check upon that.”

Highlighting the revolutionary nature of the new state constitutions, Adams stated that commissions and writs should issue under the name of the state rather than a ruler. Republics are governments “of laws, not of men,” Adams stressed.

Adams closed his published letter with a flourish. “When!” he asked, “had three millions of people full power and a fair opportunity to form and establish the wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can contrive?” To him and other patriots, 1776 was less about defeating Britain and gaining independence than about founding representative governments and securing individual liberty. “In truth it is the whole object of the present controversy,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in June 1776 about the new constitution then being drafted for Virginia, “for should a bad government be instituted for us in future it had been as well to have accepted at first the bad one offered to us from beyond the water without the risk and expense of contest.”

In a year largely remembered for military actions and the Declaration of Independence, most states went about drafting new constitutions that ended royal rule by instituting republican governments along the lines outlined by Adams and endorsed by Jefferson. “All political power is vested in and derive from the people only,” North Carolina’s constitution of 1776 began in a ringing affirmation rejecting the divine right of kings and proclaiming a new era of popular sovereignty. A bill of rights enshrining due process and the rule of law followed in the document, along with a list of grievances against George III. In consequence of his actions designed to reduce the American colonies “to a state of abject slavery,” the constitution charged, “all government under the said King within the said Colonies, hath ceased.” Neither the first nor the last of the state constitutions of 1776, in these respects, North Carolina’s was representative.

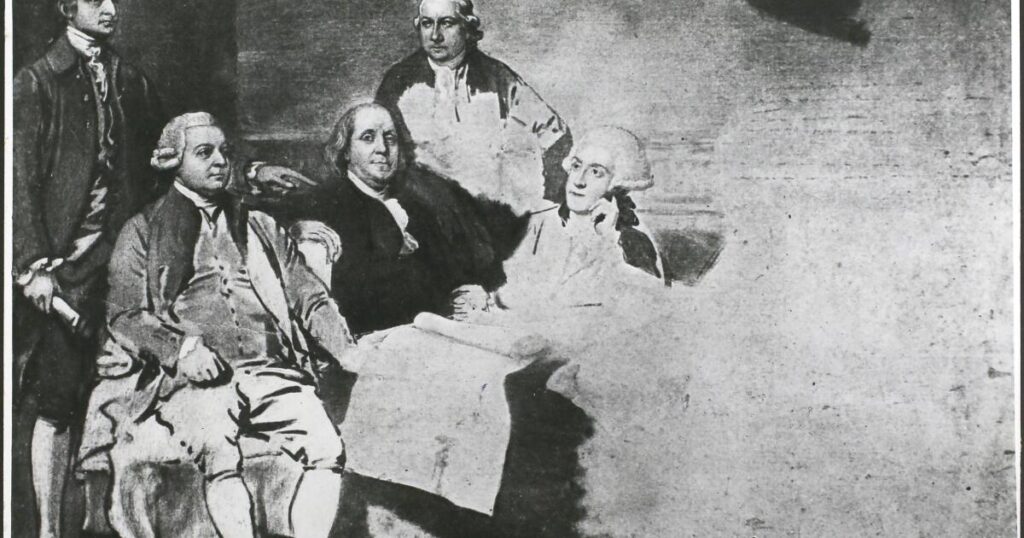

Drafted by Jefferson and unanimously adopted by delegations from every state in July, the Declaration of Independence complemented these new state constitutions. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” it famously states. “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” Individual liberty and popular sovereignty stand at the heart of this declaration, which justified independence on the basis of the king’s “repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.”

On the military front during 1776, the Americans drove the British from Boston and kept them out of Charleston, S.C., but lost New York City and Newport, R.I. On balance, despite a small but inspiring year-end victory at Trenton, the Americans ended 1776 in a weaker military position than they began it.

What changed in 1776 was Americans’ embrace of democracy over monarchy, republican rule of law over arbitrary rule by men, and written constitutions over hereditary regimes. Anticipating these revolutionary changes that would sweep the colonies in 1776 and then much of the world, Paine could justly write at the year’s outset: “The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Edward J. Larson is the author, most recently, of “Declaring Independence: Why 1776 Matters.”

The post The ‘no kings’ movement of 1776 centered on one big idea appeared first on Los Angeles Times.