Times Insider explains who we are and what we do and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

We had been working on the story for years.

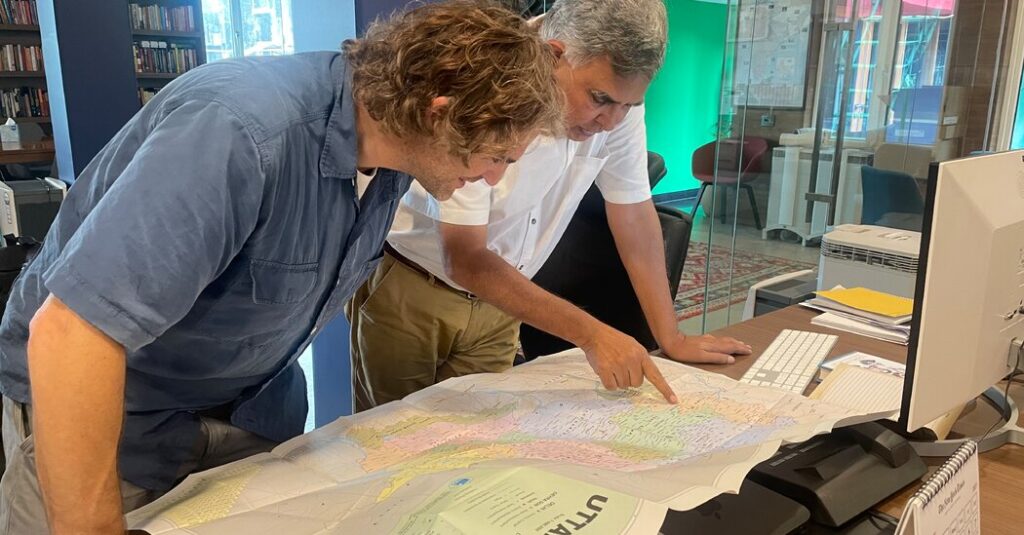

It was a complicated one, involving a secret Cold War spy mission that the C.I.A. had cooked up to snoop on China and then bungled. The mission had unfolded in the Indian Himalayas. So my longtime colleague at The New York Times, Hari Kumar, a stalwart of the New Delhi bureau, and I opened up old maps, hiked around the Himalayan foothills, unearthed once classified documents and tracked down people with insider knowledge of what happened.

We reconstructed nearly the entire covert mission, which involved the disappearance of a generator powered by radioactive fuel that posed all sorts of risks to people and the environment. The generator remains lost, which is why the story still matters.

But in November, right before we were about to publish the story, I received a text message: “We should talk,” wrote Brent Bishop, son of Barry Bishop, the famous mountain climber who helped organize the secret mission. “I found the box of files!”

He added: “It’s a treasure trove of information.”

Shoot, I thought. The trove sounded juicy, but the timing almost couldn’t have been worse. Our article was slated to be published as a special section in the Sunday Times, and for special sections we lock in the copy more than a week in advance. Complicating things even further, Brent, who is an accomplished climber himself (he has summited Everest three times) had a tiny window for me to visit, between a first-aid refresher course and a climb he was about to make in Nevada.

So I rushed off from London, where I live, to Seattle, where he lives. We stayed up late into the night poring over the files piece by piece. It was overwhelming how much he had found: bank records, phony business cards, handwritten notes, typed letters, old receipts, telegram copies, intelligence briefings, secret material about the missing nuclear device, even menus for the climbers. Those included honey, Toblerone chocolate, biscuits and something called bacon bars.

The files revealed a whole new layer to the mission that few knew about and had never been published before. Barry Bishop, with the C.I.A.’s help, had created an elaborate cover to obfuscate the real reason a team of India’s and America’s best climbers were about to disappear into the Himalayas. Reading all the material was like stepping into a scene from “Argo.”

I was excited but stressed. We had only a few days to digest all the documents and integrate them into what we had already written.

I’ve worked as a correspondent at The Times for more than 20 years, mostly in Africa, India and Europe. Hari has worked for us in India for nearly 30. And this sometimes happens — you’re nearly done with a big story and someone important suddenly agrees to talk with you, or you find some key document. Then you need to figure out how the new information relates to what you have already collected. It’s like finding new pieces to a puzzle you thought was done and dusted. Now you need to take it apart and figure out where the new pieces fit.

Luckily, the Print Hub, which runs The Times’s print operations, was able to push back our publication deadline by a couple of weeks to early December to give us enough time to make sense of what we had just discovered.

Another reporting challenge: The mission to Nanda Devi (the name of the mountain the C.I.A. chose for its surveillance station) took place in 1965. Only a few people, in their late 80s and early 90s, knew the salient details of what transpired. A paper trail was even more important for a story like this.

And now it was even longer.

The story we ultimately delivered is a narrative-driven feature that starts with the perilous journey up the icy slopes of Nanda Devi and ends in the present day, with the nuclear device still out there, somewhere, and the key players trying to make sense of what they did. It’s a blend of memory, description, scientific analysis and documentary evidence. Our Graphics and Photo departments brought the story to life, showing the key players, then and now, and explaining how all the science works and the risks that still exist.

Brent tried to talk with his father about the mission before he died in 1994.

The younger Bishop didn’t get very far. His father acknowledged his involvement but didn’t say much.

But as we sat together on a rainy, cold Seattle night, looking over a table stacked with papers that his father had meticulously kept (and kept secret), it was as if he were talking to us.

And we listened.

Jeffrey Gettleman is an international correspondent based in London covering global events. He has worked for The Times for more than 20 years.

The post Just Before Publishing, a Reporter Receives a Crucial Tip appeared first on New York Times.