President Trump’s operation to capture Nicolás Maduro, the ousted president of Venezuela, and his wife, seems to have been a military success. What is far less clear is what happens next. Stephen Stromberg, an editor in Opinion covering politics and economics, joins the columnists M. Gessen and David French to discuss the legality of America’s attack on Venezuela, the state of the global order and what “America first” means for MAGA now.

Below is a transcript of an episode of “The Opinions.” We recommend listening to it in its original form for the full effect. You can do so using the player above or on the NYTimes app, Apple, Spotify, Amazon Music, YouTube, iHeartRadio or wherever you get your podcasts.

The transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

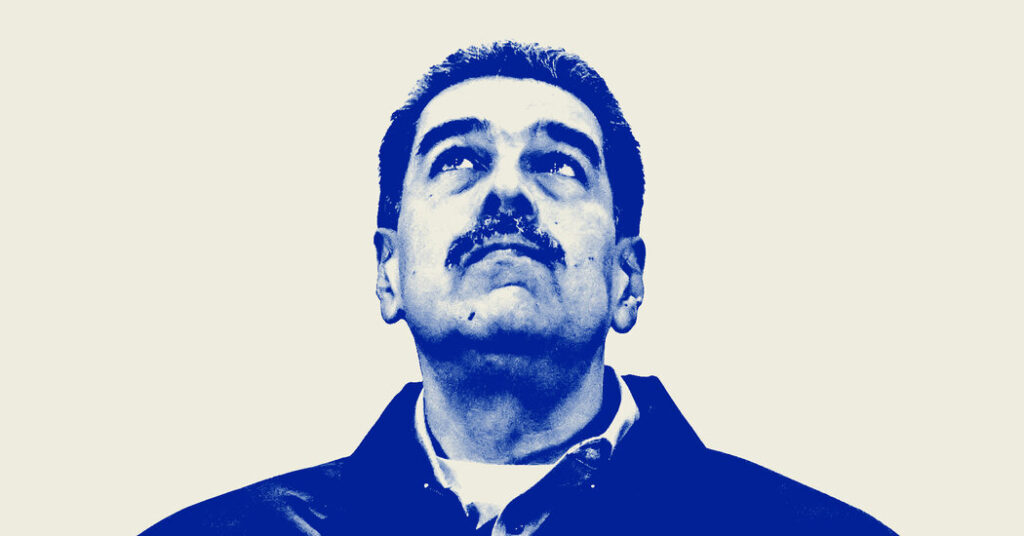

Stephen Stromberg: Masha, David, you both write about international law and justice and, of course, about President Trump. David is also an Iraq war veteran and a former JAG officer. You’ve both written columns about the U.S. attack on Venezuela and the capture of Nicolás Maduro and his wife, who are now in New York City to appear in court.

In the weeks leading up to last Saturday’s strike, many observers speculated that a major military action might be coming. The Trump administration had been blowing up suspected drug-running boats off Venezuela’s coast and amassing military resources in the area.

Briefly, what was your very first reaction to the news of the military action and capture of Maduro? David?

David French: I would say the very first thought that came into my mind was: The ends do not justify the means here. I’m very pleased to have Maduro gone from Venezuela. However, I’m not pleased in the way that it was done, and my concerns about the latter far outweigh my happiness or satisfaction about the former.

Stromberg: We’ll definitely get into that. Masha, what did you think right after you heard about the strikes?

M. Gessen: I’m impressed with how civilized David’s first reaction to the news was, as mine was probably not fit for a family newspaper. But I agree, and I was looking at it partly through the eyes of a lot of Russian dissidents — who, I think, in our dreams, we see somebody swooping in and removing Vladimir Putin.

But not like this. Because I agree that the ends don’t justify the means, and the means here are the means of really demolishing any semblance of hope for international law, for respect, for norms, for a post-World War II order that we hadn’t still given up hope of creating.

Stromberg: Let’s get into some of that. David, how does this strike compare with previous U.S. military operations? I’m interested specifically in how the Trump administration’s justifications stack up, relative to history and to international law, and simply to what countries should have to do to justify military action.

French: That’s a great question, and I’m not going to be one to sit here and defend all our military actions before this one. There have been many lawless military actions, especially in Central and South America, over the many years of American history. But I would say, even by the standards of some of our most brazen, lawless military actions, this one stands out.

When I talked about “the ends don’t justify the means,” I was talking an awful lot about the lawlessness of the action itself. First, it’s an aggressive war, waged without legal justification, in violation of the U.N. Charter, which we are a party to, by the way.

Ever since World War I, the Western powers have been trying to come to a world consensus against the notion of aggressive war, without a direct attack on the United States or an act of collective self-defense, according to treaty. For example, going in and seizing the head of state with military force is an act of war. And when you look at the justifications, though, it begins to become even more disturbing. Because what they’re looking back at is a historical record, and they’re relying a lot on the 1989 invasion of Panama. That’s a real problem for them, for one reason, and for us in the world order, for another reason.

So the problem for us as we’re looking at it is, really, there’s just no real comparison between the two, in the sense of what were the events leading up to it. Right before the invasion of Panama, the Panamanian government declared a state of war against the U.S., so that’s a big difference.

No. 2, the Panamanian government had killed a Marine, seriously injured another and had taken another service member into custody, where he was brutally beaten. So you had direct attacks on American military forces. You had — not congressional authorization for war — you had a bipartisan consensus here. You had some congressional action afterward, as well, that essentially ratifies many of the president’s actions. That’s very, very different from here. This is completely unilateral.

The other thing that’s a real problem, I think, for the nation, going forward, is the legal justification that the administration used in ’89 had its own problems.

And in ’89, they used a Bill Barr legal opinion to justify the actions in Panama that essentially said: When there has been an indictment of a foreign person — like, in that case, Manuel Noriega, in this case, Maduro — then there’s going to be a way in which American law enforcement can then execute that indictment, perhaps with the assistance of the American military.

Why is this such a problem? What a short circuit of the entire process of declaring war: We don’t need an authorization for the use of military force against Saddam Hussein. Let’s just indict him for trying to kill George H.W. Bush, and then use the 101st Airborne and First Marines to protect the F.B.I. when they arrest him. No, that’s absurd. That’s a self-reinforcing bootstrapping of war-making power into the executive, at the expense of the Constitution.

So there are big differences with previous American military engagements and also the legal justifications for past American military engagements are being bootstrapped into this one or being brought into this one in a way that’s extremely dangerous for the future of separation of powers and accountability of the executive.

Stromberg: So you don’t buy the argument that this is not, in fact, a military action but actually something more like a law enforcement action.

French: Totally absurd. It’s just totally absurd. It doesn’t pass the straight face test. If you use the U.S. military to enter into a foreign capital and seize the head of state, I don’t care if you have a couple of F.B.I. agents with you. This is an act of war.

Imagine if you had an indictment of Donald Trump for, say, some sort of financial crime in the United Kingdom or France or whatever, and they execute a raid in the White House with air support. Would we sit there and go, “Well, what a spectacular police operation that was just executed?” No. Everyone would know that was a brazen act of war. There’s nothing civilian about this, despite the fig leaf of the F.B.I. presence in the actual attack.

Stromberg: Masha, you’ve observed Putin as closely as anyone. You mentioned him a little bit earlier in this podcast. What is he thinking right now?

Gessen: Let me just pick up where David left off, and then I’ll go to Putin. I think this is one of those times that the Trump administration has done something where an increase in quantity really creates an entirely new quality of phenomenon. Things that are somewhat like this invasion of Venezuela happened before. The United States has gone to war without the authorization of the United Nations. The United States has engaged in regime change. Presidents have carried out strikes on foreign countries without briefing Congress.

But the combination of all of that, the scale of all of that, the amount of time that has now passed without Congress still being briefed — we’re taping this on Monday morning, and from what I understand, there still hasn’t been a briefing for Congress, and we’re two days out from the operation.

And then the rhetorical framing of it, Trump standing in front of reporters and repeating in various ways: “We’re going to run that country” — all of that just puts us in an entirely different kind of territory, and I think it’s terrifying.

As for Putin, I think that early on Saturday there were some commentators who said: Oh, Putin is probably upset because Maduro was his ally. Venezuela has been historically an ally of Russia. But I think actually this operation comports with Putin’s worldview perfectly. He views the world as a place that some very powerful men can carve up. They can make backroom deals, and they can decide where their spheres of influence are. It’s sort of the other post-World War II order. It’s not the legal order, the liberal order that we usually refer to. It’s not rights based. It’s not human rights based. It’s men sitting around in Yalta saying, “You take that, and we’ll leave you alone, and we’ll take this.”

And this is exactly what Putin has been advancing in his speeches and his articles and in his actions for more than a decade. So to him, this is a signal that his hands are untied in Europe.

Stromberg: Let’s dig a little deeper into the broader implications. Yalta, of course, was the site of a summit near the end of World War II, where the major Allied powers determined the postwar territorial order in Europe. I’m reminded of a 2012 presidential debate in which President Barack Obama criticized Mitt Romney for adopting the foreign policies of the 1980s, saying something like, “The 1980s are calling. They want their foreign policy back.”

Trump, by contrast, is reaching back to something more like 1908, maybe.

Gessen: 1823?

Stromberg: Speaking of that, on Saturday he invoked the Donroe Doctrine, which seems to envision splitting the world into three major spheres of influence led by the United States, Russia and China. That gives off a Cold War vibe. Trump’s desire to dominate areas physically close to the United States reflects even older thinking: We invaded Iraq, and the problem was that was 10,000 miles away, whereas this is in our backyard. Does any of this make sense in the world of the internet and B-21 bombers rather than steamships and cavalry charges? David, why don’t we start with you?

French: When you said the ’80s called, and in the case of Trump, we all have our different date range. I was thinking 1880 and the gunboat diplomacy of the Gilded Age. I don’t necessarily think that technology is changing that dynamic as much as technology might be changing the consequences of conflict, the way it does so often. The Industrial Revolution made conflict so much more deadly. The nuclear age can make it even more deadly still.

But when Masha talks about this carving up of the world, I think that is really the key insight here, because let’s go back and look at why we have this much-maligned world order to begin with. The architects of it — almost all of them had been through two world wars by that point. World War I was so catastrophic, it was called the “war to end all wars.” It had 16 million to 18 million people who died in it.

Well, the structures and institutions designed to prevent World War II failed utterly, largely because we didn’t participate in them. So then we had World War II, which was even worse than World War I, beyond human imagination — that’s how bad it was.

So after World War II, we tried again. What are the institutions that we can create that can prevent a World War III? That’s the central animating, virtuous purpose of, say, the United Nations. But this time we participated. We participated with the other four victorious powers, creating a U.N. Security Council. And you can barely hold this together with three of the five permanent members largely complying with the laws of war and the rules of international engagement, so long as one of them is the United States of America. You can deter China; you can deter Russia — although we’ve had a failure of deterrence in Ukraine, of course. There’s a way to deter.

But if you take the United States and pull it out of the intended way the U.N. is supposed to function, the way the international institutions are supposed to function, and put it right beside Russia and China in not believing in the post-World War II order but believing in spheres of influence and great-power competition, more a pre-World War I order, then the whole thing cannot be sustained. It will collapse.

A lot of people will look at this post-World War II order and say I’m too Pollyanna-ish about it. I look at it with rose-colored glasses. It’s failed in many ways. Yes, it has. There has been an aggressive war. Millions of people have died in armed conflict since World War II. But what it has been very good at is that it’s accomplishing its central purpose, which is preventing that global, total war that we experienced two times in the previous century.

.op-aside { display: none; border-top: 1px solid var(–color-stroke-tertiary,#C7C7C7); border-bottom: 1px solid var(–color-stroke-tertiary,#C7C7C7); font-family: nyt-franklin, helvetica, sans-serif; flex-direction: row; justify-content: space-between; padding-top: 1.25rem; padding-bottom: 1.25rem; position: relative; max-width: 600px; margin: 2rem 20px; }

.op-aside p { margin: 0; font-family: nyt-franklin, helvetica, sans-serif; font-size: 1rem; line-height: 1.3rem; margin-top: 0.4rem; margin-right: 2rem; font-weight: 600; flex-grow: 1; }

.SHA_opinionPrompt_0325_1_Prompt .op-aside { display: flex; }

@media (min-width: 640px) { .op-aside { margin: 2rem auto; } }

.op-buttonWrap { visibility: hidden; display: flex; right: 42px; position: absolute; background: var(–color-background-inverseSecondary, hsla(0,0%,21.18%,1)); border-radius: 3px; height: 25px; padding: 0 10px; align-items: center; justify-content: center; top: calc((100% – 25px) / 2); }

.op-copiedText { font-size: 0.75rem; line-height: 0.75rem; color: var(–color-content-inversePrimary, #fff); white-space: pre; margin-top: 1px; }

.op-button { display: flex; border: 1px solid var(–color-stroke-tertiary, #C7C7C7); height: 2rem; width: 2rem; background: transparent; border-radius: 50%; cursor: pointer; margin: auto; padding-inline: 6px; flex-direction: column; justify-content: center; flex-shrink: 0; }

.op-button:hover { background-color: var(–color-background-tertiary, #EBEBEB); }

.op-button path { fill: var(–color-content-primary,#121212); }

Know someone who would want to read this? Share the column.

If you think you can just yank the U.S. out of it or think we can go back to 19th-century gunboat diplomacy and spheres of influence — which, by the way, it’s never so neat that the great powers all agree on what their spheres are and harmoniously go about their business in their respective spheres. That is not the way this works, and if you look at it from that standpoint of what it was designed to do and what it has done, as imperfect as it’s been, it’s blocked, it’s stopped, it’s prevented the nightmare. And when we mess with the systems that have prevented the nightmare, we risk the nightmare. And that’s what makes me so concerned about where we are.

Stromberg: When we talk about the international order, the post-World War II order, the criticism that often comes to mind focuses on the economic system that was built. But in many ways, that economic order — the I.M.F., the World Bank and other institutions — was ancillary, in service of the primary mission you described: preventing another world war and ending the great-power competition that led to those human catastrophes.

We have a war on the ground right now in Europe, in Ukraine. And I’m wondering — these are obviously very different situations, Venezuela and Ukraine — but I do wonder how you see this action in Venezuela interacting with the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Gessen: They’re different, but they’re also similar. I think it’s actually a good moment to focus on those similarities. Obviously the difference is that in one case, the United States went in, removed a dictator who had been holding on to power by falsifying elections. That’s Maduro. In the other situation, Putin went in as an act of aggression to try to remove a legitimate democratically elected president in Ukraine. But the design of those missions was remarkably similar.

What Putin envisioned was that he was going to bomb Kyiv, swoop in, remove Zelensky and, using the rhetorical cover of liberating the people of Ukraine, repairing infrastructure that had fallen into disrepair — you could almost word for word use Trump’s news conference after the Saturday operation to write what Putin imagined he would be saying if his initial military foray into Ukraine hadn’t failed.

So I think that similarity is super-important to keep in mind as we analyze what has happened to the world that we live in. And four years into the war in Ukraine, Trump has been pressuring Ukraine to agree to a poor peace deal that would be hugely disadvantageous to Ukraine but would give him a feather in his cap and would maybe, finally get him the Nobel Peace Prize that he dreams of.

The message that Venezuela sends, combined with the pressure Trump has been exerting on Ukraine, is directed at the rest of Europe. And that message is that Europe is being left on its own in the face of Russian aggression. Putin has made it very clear that he’s not going to stop at Ukraine. Russian hybrid warfare in Europe — which I think many people in this country aren’t fully aware of — has been ongoing for years and has really intensified over the last year. That includes political meddling, sabotage, acts of terrorism and the jamming of radio frequencies at European airports. It’s become almost routine.

Stromberg: Let’s shift focus for a minute. Let’s look at how people are responding in the United States. David, the Venezuela attack violated one of Trump’s most consistent campaign promises. In all three of his presidential races, he promised to end American interventionism abroad. It was crystal clear. He’s now saying he will run Venezuela until a proper transition can take place but hasn’t really defined what that is. He has threatened to intervene in Iran if peaceful protesters are killed. He keeps talking about Greenland. So this has riled people, such as the former Trump ally Marjorie Taylor Greene, who’s criticized Trump and his focus on foreign policy rather than on domestic matters.

How, if at all, does his flexing of American power abroad fit into MAGA’s “America first” ethos? Can Trump defend or explain his actions to the MAGA base in a way that will satisfy his supporters?

French: Easily on this, because this is not their first rodeo when it comes to foreign intervention. The bottom line is that I believe a lot of MAGA’s rhetoric about war has been much more a matter of internal Republican politics than it has been a deep-seated principle.

I do think that there are some people in the Republican coalition who are old school, longtime Patrick Buchanan types who might have some discomfort with this. But 99 percent of MAGA is not old-school paleoconservative Patrick Buchanan types. MAGA truly is a relatively new phenomenon that is much more centered on the personal success of Donald Trump than it is on a particular ideology.

Had this mission failed, had a helicopter been shot down and American soldiers had been killed, had it turned into a Desert One-type fiasco like Jimmy Carter had in the sands of Iran, there might’ve been some rumblings, but this comes across as a big Trump win.

To test out this hypothesis, that this is not going to be an issue at all, I did a perusal very, very late last night through some of the Twitter feeds of the MAGA figures who’d been most derisive in mocking toward people like me, for example — Reagan/Bush-era conservatives. I found them being very mocking and derisive but against anyone who is criticizing the operation in Venezuela. This is not the Epstein files, and not even the Epstein files have really driven a true wedge between Trump and MAGA. They have opened some fissures, some very slight cracks, but this is not something that really hits at core convictions of some key members of the coalition. No, no, no. This is something else.

The foreign policy side of the MAGA fight hasn’t really been a grass-roots issue so much as a grass-tips or grass-tops issue, something driven by competing ideological factions within the Republican Party that don’t actually have much hold over the populist MAGA movement itself. But I do think the moment something like this goes poorly for Trump — when he isn’t seen as having accomplished something remarkable — that dynamic could change. This military operation appears to have been brilliantly executed, and that’s allowed Trump to adopt a victorious posture, which I think his base ultimately loves more than any particular ideology.

Stromberg: Masha, how do you see this? Is MAGA just a Trump personality cult? They’ll be happy as long as he seems successful? Or is it more complicated than that?

Gessen: Yes, it is just a Trump personality cult. Also, I think Trump is either discovering or remembering what other autocrats have known for a long time: There’s no easier way to build “greatness” than to wage imperial wars. It’s much harder to build greatness by making people’s lives better at home. Trump has not been very good at that. But to project greatness by taking over neighboring countries, well, that trick is as old as autocracy itself, and it usually works. It works particularly well in a fractured media universe like the one that we live in now.

David is right that Trump is lucky to some extent, in that this operation did go extremely well — to the extent that we can evaluate the military operation. What’s going to happen on the ground in Venezuela? We have no idea. Nobody seems to have given that any thought. But even if it hadn’t gone well, the MAGA media universe is going to project that very far away place and events that are happening outside anybody’s field of vision as further proof of Trump’s greatness.

Stromberg: It does interest me that Stephen Miller, who’s a senior Trump aide, an immigration hard-liner, early MAGA believer and somebody who actually really does care about specific outcomes, reportedly favored the Venezuela attack. I think he and folks like him might care because they want Venezuelan migrants to leave the United States and to prevent more from trying to come here. Do you think that is enough to square the Venezuela attack with “America first”? What kinds of justifications are they going to come up with to sell this?

French: I think it’s very important to understand that when Trump is saying “America first” and when this Trump movement is saying “America first,” we cannot think of it as isolationist. That is not what it is. It is spheres of influence. That’s the way that we need to think about the Trump mind-set right now. “America first” means just: America runs its sphere of influence. This is the main consideration.

If American national interests dictate that, say, Maduro needs to go, then unlike previous administrations — which would say, yes, Maduro needs to go, but we need to do this in a lawful way. In that circumstance, what we have to do is exercise diplomatic economic pressure to achieve national interest.

The way the Trump administration views it is much closer to Carl von Clausewitz: War is an extension of policy by other means. So if persuasion fails, if diplomacy or economic pressure fails, then that alone becomes reason enough for war within the American sphere of influence. You really began to see this in the first hours of Trump’s second term, when he started bullying Canada and Mexico. At that point, it should have locked in: Oh, Canada and Mexico are like Trump’s Ukraine. They’re nations in our sphere of influence that we, as the biggest kid on the block, should be able to dictate terms to — to create economic arrangements more favorable to us — and their national interests don’t matter at all.

That’s what “America first” is in this second Trump term. It’s not truly isolationist. It’s much more a so-called Donroe Doctrine. And if anyone doubts that, just look at the laundry list of countries he’s suggested need some form of American intervention. He’s talked about Colombia. He keeps talking about annexing Greenland. And at this point, I’m not even chuckling about it anymore. It sounded weird and fantastical at first, but he won’t let it go. I still don’t think it will happen, but it’s so consequentially awful, and Trump is so erratic and so demonstrably willing to act on his own authority, full stop, that I’m now worried he might conceivably do something dangerous in Greenland.

In fact, the Danish government is concerned enough that it recently issued a very clear public statement. And if you want to talk about something that would absolutely wreck NATO at its core, at its foundation, it would be seizing the territory of a NATO country — which could arguably allow that country to invoke Article 5 against us. Just imagine that for half a second. We’re in a world right now where “America first” means only American interests matter within this sphere of influence and force will be used — liberally — to accomplish what Trump believes those interests are, on his own authority, on his own accord.

That creates tension abroad. And when you engage in serial military actions without building public consensus at home, it creates tension at home, too. There hasn’t been the kind of rally-around-the-flag effect — at least not yet — after the Venezuela operation that we’ve seen after many other military actions. I think part of that is that he didn’t prepare the American public for it. He didn’t sell it. He just did it. And when you put all of this together, “America first” isn’t isolationist; it’s sphere-of-influence-based, and it’s very, very, very aggressive in Trump’s second term.

Stromberg: “Spheres of influence,” I guess, is the phrase of the month. Maybe the phrase of our future. Trump is claiming some particular interest — rights — in the Western Hemisphere that was mapped out in the national security strategy that his administration recently released. But also, as we mentioned before, he struck Iran in concert with Israel. He has tried to play peacemaker in Gaza, in Ukraine.

So are spheres of influence even the best way to think about it? Is it that we have our backyard, where we have a particularly strong interest, but we really have interests everywhere that the United States can pursue and defend? How do you see this, Masha?

Gessen: I’m going to mount an argument against using the term “spheres of influence,” because “spheres of influence” generally implies using soft power and the threat of hard power to exert influence. That’s not what we’re seeing. We’re seeing colonization of an entire country. That’s beyond spheres of influence. We need some other term for it, probably something better than “the Donroe Doctrine,” but at least I would favor that because it’s new.

One thing I want to add in thinking through how Trump views all of this — and how MAGA views it — is that Trump is a president who watches himself on television and has a remarkably good memory for certain things. Some of what he remembers from his first term is dropping the “mother of all bombs” for the first time and suddenly getting a lot of television buy-in, even from traditionally liberal talking heads. He saw that as a way to assert himself as presidential. Something else he’s clearly fixated on, for very good reason, is the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan during the Biden administration. And I think when he compares the television images of the extraction of Maduro with the television coverage of the withdrawal from Afghanistan, it inspires him to do more things like this.

So rather than think about what’s in the American interest — in the way someone like Stephen Miller might think about it or even the way a totally unhinged national security strategy might articulate it — think about how he imagines the television picture. What’s going to look great?

Stromberg: I think an apt way to think about a lot of his psychology is that he’s famously a cable news addict. So the question becomes: How is this going to play in the short term and the long term across America? Successful military operations — and this one was really successful — generally attract public support. Could the American public see some logic in directing Venezuela remotely, through coercion, backed by air and sea power?

French: I think the actual realistic answer about American public opinion is that nobody is going to be talking about this very much in days — not weeks — if nothing else happens. Even if there’s some violence or chaos on the streets in Venezuela, people will check out from this. Why? Because Americans aren’t there and Americans aren’t being harmed by it.

There’s a long history of American intervention in South America. The gunboat diplomacy era — there were serial interventions into Central and South America that didn’t leave much of an imprint on American politics at home or American public opinion at home compared with other kinds of wars and conflicts.

What American presidents do in Central and South America tends not to really matter to American public opinion unless it creates a crisis at home. So presidents tend to have this free hand that then allows them to do things like Trump did and create an environment in Central and South America that actually ends up to be deeply harmful for the entire region. So the region itself struggles and suffers because of serial American engagement, serial American involvement. But the American people are largely checked out of it. And to me, that creates a particularly dangerous kind of situation.

You can create the conditions for a foreign policy disaster largely immune from any kind of real public scrutiny and accountability in the meantime. I know there’s a lot of interest in this right now, but again, unless there’s a big crisis, that will fade. And that gives Trump a lot of room to maneuver and to put us into a position that could get very dark very fast.

So Trump’s got a free hand for now, but he’s unleashing chaotic forces. And if those chaotic forces create consequences during this term, he’ll feel it.

Gessen: And that will mean starting other wars, right?

French: Potentially.

Stromberg: Elaborate on that, Masha. If this becomes a crisis, he’s going to be invading or decapitating the regime in Havana? What’s your prediction there?

Gessen: Steve, we all know better than to make predictions, so I’m not going to name countries. But I’m going to say that the autocratic playbook distracts from bad wars with new, better wars. Because the television effect of Venezuela is going to be short-lived. And David is absolutely right: Americans are going to stop thinking about Venezuela and stop talking about it in a matter of days. So to have another hit, Trump is going to want to have another hit.

Stromberg: David, you’re nodding your head. Anything you’d add there?

French: Yeah. I love Masha’s formulation of reading a playbook versus forming a prediction. The playbook here is historically quite clear, and with Trump, so far, it’s been clear. Authoritarian personalities, when they face military adversity, do not tend to back away like somebody has touched a hot stove. They tend to double down because, as Masha said, that is the way to glory. That is the quickest way to truly achieve — at least in their own mind — this stature, this power, this historical weight. It’s accomplished through armed conflict.

One thing we’ve seen is that Trump — and this is what makes me very nervous — believes he’s hacked the system. He thinks he’s figured out how to use force in a way that Bush, Obama, Clinton, the Bush before him and Reagan just didn’t know how to do, and that was: Never put an actual boot on the ground, or if you do, do it in such a way that the risk is minimal.

Instead, his approach is to hammer, hit hard, leave and end it. But there’s a reason that hasn’t been the pattern or practice of previous presidents who wanted to create enduring change. It’s because it doesn’t work. It can create very specific real-world outcomes. When Qassim Suleimani of Iran was killed in a strike, for example, that was a very significant real-world outcome. And of course, seizing Maduro would be a very significant real-world outcome as well. But as a general matter, in the absence of real, long-term investment in a place or a region, those actions end up being little more than cosmetic — window-dressing operations. They don’t have an enduring impact.

What happens instead is that they create more reasons for future conflict, because you haven’t actually transformed conditions on the ground. You get one quick hit, then another quick hit and another quick hit. But each one carries risk. There is no such thing as having hacked war. That’s what concerns me. You have a person unleashing historical forces that are not within his control, without any sense that he understands he’s doing this or that he can handle the knock-on effects of what he’s unleashing.

We have international rules and laws for very good reasons. They weren’t dreamed up by people sitting around a conference table trying to oppress America. They’re built on hard-earned wisdom and experience. Disregarding them risks unleashing forces beyond Trump’s control.

Stromberg: And on your point about hacking the system: I think another element of his thinking is that “Oh, those fools who came before me cared about things like human rights and democracy. We will be much smarter in simply absorbing the current government, the existing government and structures, no matter who’s in charge.” It’s a little bit more Kissengerian.

OK, let’s wrap up. What specifically will each of you be watching over the next few days, weeks, months? Let’s start with Masha.

Gessen: I don’t know about watching, but I’ll tell you what I’ve been thinking about and what I think we haven’t quite touched on, which is: I’ve been working on a series on international justice for the last few months, based on the premise that we’re at a real crisis point in international injustice.

On the one hand, there’s Ukraine, and there was real hope of seeing the multilateral structures of international justice really kick into action because there was such robust consensus on what was happening in Ukraine. And then there was Gaza, and that consensus shattered. And so I’ve been traveling around and talking to different people and covering different processes.

What has just happened, I think, has really shattered an 80-year-old hope for a world order that’s not only intended to prevent global war — which David has talked about, and he’s absolutely right — but it’s also a fundamentally humanistic project. It’s a project based on affirming the value of human life and affirming the value of human dignity.

That’s why it includes protections from war crimes, protections from civilian casualties, protections for asylum seekers as part of our — at least intended — international order. And the Trump administration has been waging an attack on these multilateral structures since the beginning. Well, since, really, his first term but in an all-out way since the beginning of his second term. And this extraction of Maduro under the rhetorical cover of pursuing justice is possibly a fatal blow to this hope of creating international justice.

French: What I’m looking for and what I’m concerned about is something we’ve been talking about, kind of weaving throughout, which is: What do Trump and his team mean when they think about Make America Great Again?

Are they thinking about peace and prosperity, or are they thinking about power and majesty? I think it’s becoming pretty clear that they’re thinking more about power and majesty. One of the reasons I raised that is if you look at some of that rhetoric from Stephen Miller, who — he looks back at the post-World War II era as a time when essentially the Western world gave away its majesty and might. Well, wait a minute. The Western world post-World War II reached heights of prosperity and peace internally and on the European continent that are unprecedented in world history and without comparison in European history. There’s not the same power and majesty, but there’s infinitely greater peace and prosperity and, critically, justice than there was under the colonial structure.

But that is not what they’re after. That is not the fundamental, ultimate motivation. So we’re talking about a movement very much animated by grandeur, by power, by majesty, by might. And when you understand that, you can begin to see the scale and the dimension of the risks that we’re facing, going forward.

Stromberg: David French, Masha Gessen, thank you for being here today.

French: Thank you so much.

Gessen: Thank you, Steve.

Thoughts? Email us at [email protected].

This episode of “The Opinions” was produced by Derek Arthur. It was edited by Alison Bruzek and Kaari Pitkin. Mixing by Carole Sabouruad. Original music by Sonia Herrero and Carole Sabouraud. Fact-checking by Marge Marge Locker, Michelle Harris and Kate Sinclair with help from Vishakha Darbha. Audience strategy by Kristina Samulewski. The director of Opinion Audio is Annie-Rose Strasser.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Is This MAGA Foreign Policy or Something Else Entirely? appeared first on New York Times.