People are dancing and somebody comes up with an eye-catching new move. Other people copy, vary it. Moves like it accrue into a dance style, and the style gets a name.

This has been going on in America for hundreds of years. Most often, it has been Black Americans who have done the inventing, moving on to the next thing as the old one is picked up by the wider population. Some people, though, stick to a style, deepen it and pass it on with pride.

“American Street Dancer,” a touring production by the acclaimed hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris, traces the common roots of street dance in African rhythms and American tap dance and then showcases three regional styles: Detroit Jit, Chicago Footwork and, from Harris’s hometown, Philly GQ.

The New York Times invited cast members of “American Street Dancer” to demonstrate the fundamentals of the three styles. It was an extremely lively history lesson in continuity and change.

Detroit Jit

The name is generally said to derive from the Jitterbugs, a trio of Detroit brothers who started dancing together in the 1970s (and traced the name to local slang for criminals). Some of the twisty jazz steps they adapted to funk music recalled an earlier generation of jitterbug or Lindy Hop dancers, but more of their moves came from the tap teams of the swing era like the Nicholas Brothers, as fed through Motown groups like the Temptations (who were choreographed by the tap dancer Cholly Atkins). Both smooth and spectacular, the Jitterbugs would spin down to the floor then unwind right back up, only to flip forward and land in splits.

Michael Manson Jr., the leader and choreographer of House of Jit, acknowledged the importance of the Jitterbugs but also pointed to other Detroit crews — Madd Dancers, the Dream Team — who sped up their moves as local music accelerated into techno and ghettotech in the 1990s and early 2000s.

“The foundation comes from tap,” Manson said. “When I talk to jit elders, they always say: ‘We didn’t take classes. We imitated what we saw on TV.’” What they saw were movies with the Nicholas Brothers and other Black dancers immortalized in Hollywood musicals.

Shuffle

That foundation is clear in the first move that Manson demonstrated with his colleague Tristan Hutchinson: the shuffle. “We know what we are doing because of the sound on the floor,” Manson said. “I know my man is with me because I can hear him.”

Kick Wiggle Back

After showing the self-explanatory Kick Wiggle Back, Manson noted the precedent for such kicking and wiggling in the Charleston, the dance that was born in Black neighborhoods and exploded into cultural ubiquity in the 1920s.

For advanced jit dancers, these steps are the basics, which must be done correctly to earn respect — and jumping-off points for the make-it-your-own variations of individual style.

Chicago Footwork

Dancers of jit and footwork have a longstanding argument about which style came first. (Manson said that the influence flowed from Michigan to Illinois when Detroit hair stylists brought jit dancers with them to hair shows in Chicago.) But nobody disputes that the Chicago way is even faster. It emerged in the late 1980s and ’90s, when DJs took the house music that had developed in Chicago’s underground clubs and jacked up the tempo. The amphetamine-spiked pulse of footwork music, also called juke, matched the manic swivels and scissoring of footwork dancers, who faced off in dance battles.

Erk ’N’ Jerks

Donnetta Jackson and Eddie Martin Jr. of Creation Global showed one of the oldest moves: Erk ’N’ Jerks. Feet bounce together and apart, twisting toward one side and then the other, as arms dig the air in opposition.

Mike ’N’ Ikes

In Mike ’N’ Ikes (named after the chewy candy), knees and ankles pivot in and out as the body bounces percussively in pendulum motion. Jackson and Martin increase the difficulty by moving the step in a circle.

Running Man

The Running Man describes itself, except that the person running seems to be on a super-speed treadmill that pauses every three steps. “I don’t play with it,” said Martin, known in the footwork scene as Pause Eddie. He and Jackson bend deeply forward, reaching the arms opposite their standing legs nearly to the floor. That piked stance recalls Over the Tops and Trenches, tap steps introduced around the time of World War I.

Jackson, who goes by Lil Bit, was a tap dancer before she added footwork to her skill set. “I had to figure out the body and the look and the bounce, but I never had any problem with the feet,” she said.

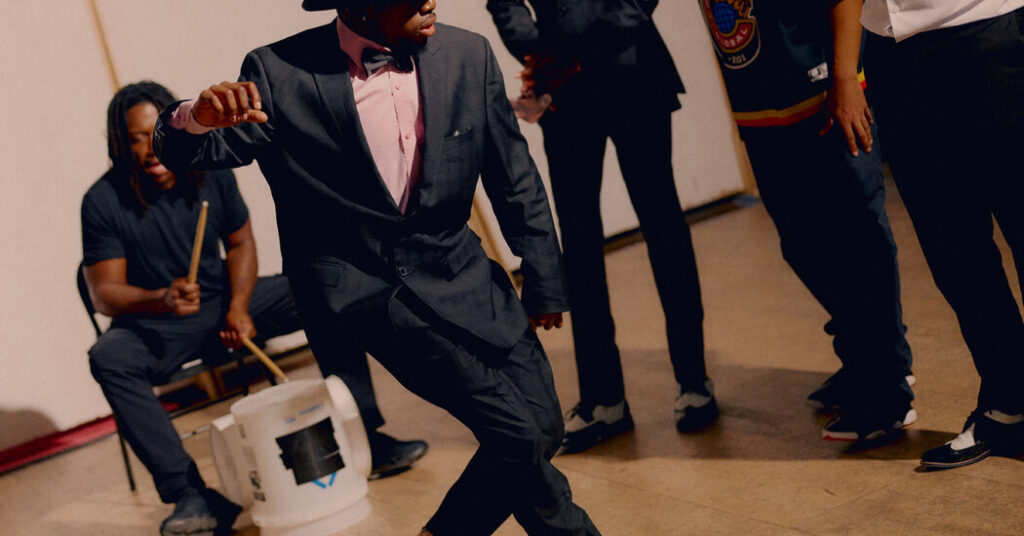

Philly GQ

Of the three styles, GQ is the most historical in that it is no longer practiced much outside of Harris’s works. (Jit and Footwork still have active communities with rival groups and battles.) He first encountered it in the mid 1970s, when he was entering his teens. “It came out of Black social clubs of the 1960s,” he said. “It started out as a partner dance, a man and woman doing the Cha Cha. But as different clubs started to challenge each other, it became more frontal and performative.”

What remained, most visibly, was sartorial style: suits, collared shirts, dress shoes. “We started calling it GQ after Gentlemen’s Quarterly magazine,” Harris said. “You always knew a GQ dancer by how he dressed.” (There were some female GQ dancers, too, who tended to wear vests instead of jackets.)

But the motions and rhythms of Cha Cha are also easily detectable in the foundational steps of GQ, as demonstrated by Tyreis Hunte and Zakhele Grabowski.

Cha Cha

“Philadelphia was a big tap town,” Harris said. He cited local tap greats like Bill Bailey and Honi Coles, who once recalled that tap dancers were so profuse in the 1930s that the city’s street corners were categorized by skill level — this one for challenge matches between beginners, that one reserved for experts.

Step Master Time Step

The presence of tap in GQ is most obvious in the percussive heel-and-toe work of moves like the Step Master Time Step.

Webster-Split

GQ also adopted the flash steps of tap acts. In the Webster into a Split, Grabowski springs into the air off one leg and rotates in a tight ball (a Webster flip) before sinking into splits and sliding back up. It’s a where-did-that-come-from move that Grabowski executes with nonchalant control. He doesn’t lose his hat.

GQ, Harris said, was almost totally a dance of choreographed routines, rather than freestyle improvisation. It was a style of collective unity with room for individual flare.

By the middle 1980s, GQ was on its way out, replaced by hip-hop crews like the one Harris joined. That eclipse doesn’t mean that GQ disappeared, though. “It’s in everything I’ve ever choreographed,” Harris said.

Harris has received more praise as a hip-hop choreographer than anyone, but he thinks that label is misleading and overused. The term “hip-hop dance,” he said, can obscure the diversity of street dance, which should really be thought of as a big family of “community” dances — styles that have differentiated from region to region, city to city, usually connected umbilically with the local music scene. Styles like jit, footwork and GQ.

After all the teams had illustrated the basics, everyone regrouped for a mixed-style jam session. That’s the ending of “American Street Dancer,” which had its New York debut at the Joyce Theater in November. It’s in that context that it’s easiest to see how each of the styles still lives, even GQ — the performers riffing off one another, borrowing, competing, conversing. Joined by the bucket drummer Edward Smallwood (best known as Uptown Eddie), the demonstrators became dancers.

The post Dance Moves From the Street, City Edition appeared first on New York Times.