“I can’t believe you haven’t read this,” my husband said one day right before Thanksgiving. He was holding Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, “Hamnet.” “This book has your name all over it.”

Haywood wasn’t the first person to tell me I’d love “Hamnet.” But I found myself avoiding it when it first came out — a book subtitled “A Novel of the Plague” was not what I wanted to read in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic — and never got back to it later on.

That was most likely a matter of unconscious design. This beautiful, haunting novel is an imagined account of the death of William Shakespeare’s 11-year-old son, and even Ms. O’Farrell found its subject a challenge. “One of the reasons I kept putting off writing the book was because I had a weird superstition about not writing it before my son was past the age of 11,” she told People magazine. My own sons are long since grown, but it takes only the smallest imaginative leap for me to fall into similar atavistic thoughts.

But the possibility of encountering a devastating plot point is not a reasonable measure by which to judge a work of art. Art is supposed to break our hearts. It’s supposed to crack us open to every raw, elemental feeling a human heart can bear. That’s how it makes us more human.

It’s also what makes the sometimes brutal world itself seem a little more bearable, if only in helping us to understand how far from alone we are. Surely this truth is as relevant in our own precarious era as it was during Shakespeare’s. We turn to art in part to make sense of a life that is heartbreakingly fragile.

At the end of a devastating year, when every value I hold close was under attack, the imagined death at the heart of a brilliant book no longer seemed to me like something to fear. So I finally read “Hamnet.” It was every bit as transcendent as Haywood told me it was.

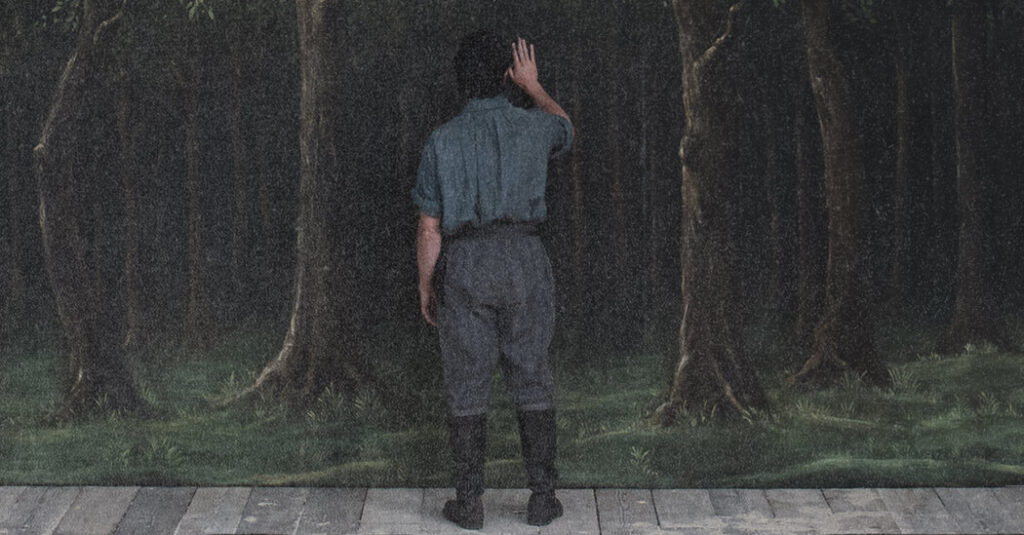

Not long after I finished reading, the film version came out. Haywood and I saw it with friends at the Belcourt, Nashville’s historic art house theater. We all left stunned by the film’s beauty and its power, by its unleashed intensity. We talked about it on the walk to dinner. We talked about it during dinner, and again at our house afterward.

For the better part of a month, I could not stop thinking about “Hamnet.” I kept returning to the book, rereading parts of it. I went back to the Belcourt and saw the film again, this time alone, registering details I’d missed on the first viewing. The more time I spent with “Hamnet,” both novel and film, the more it seemed like every glorious thing that art can be.

We don’t know how the historical Hamnet died. We don’t know whether Shakespeare wrote his great tragedy “Hamlet” in response to the loss of his son, as “Hamnet” posits. What we do know is that in Elizabethan England, where spelling had not yet been standardized, Hamnet and Hamlet were different spellings of the same name. And though “Hamnet” leads to and falls from the death of the title character, it is primarily the story of Hamnet’s mother, about whom next to nothing exists in the historical record.

In Ms. O’Farrell’s account, Agnes, “the daughter of a forest witch,” inherits her mother’s gift for healing and piercing insight. She grows up feeling “too dark, too tall, too unruly, too opinionated.” She is as out of place in the provincial world of Stratford-upon-Avon as her brilliant husband is.

The Latin tutor, as Shakespeare is called in the novel, loves her because she sees the world “as no one else does.” She loves him back because she sees in him a “landscape” of “spaces and vacancies, dense patches, underground caves, rises and descents.” She recognizes this internal landscape as “bigger than both of them.”

“Hamnet,” then, is not only an exploration of the relationship between grief and dramatic art, but it also proposes an answer to the question that continues to vex a small subset of Shakespeareans: Could a glover’s son from a muddy backwater of Tudor England really write some of the greatest works of literary art the English language has ever produced?

Of course he could. In the imagined world of “Hamnet,” this extraordinary transformation happens the same way it happens in Shakespeare’s tragedies: through a combination of character and circumstance. Shakespeare is a writer because he was born a writer. In “Hamnet,” he escapes the limitations of Stratford because he married a woman who sees his truth and encourages his gift even as she protects her own.

In other words, this is as much a book — and a film — about art as it is a tale of love and grief. It tells us something about how art is formed, and informed, not only by life but also by felt imagination.

“The Tragedy of Hamlet” is not a true account of the death of Shakespeare’s young son any more than Ms. O’Farrell’s novel is. Art simply doesn’t work that way. True art makes of life a kind of collage, a patchwork of real and unreal, of thought and memory and imagination. By the end of the story, we understand Ms. O’Farrell’s Shakespeare to be a genius by what he makes of the raw material of unspeakable grief. It’s fair to say the same for what Ms. O’Farrell has made of her own unspeakable fears. So many shards of the living world, small and large, go into making a work of art. So many shards of the living artist do so as well.

Genius is a lightning bolt. Very few of the slings and arrows that we will inevitably suffer could ever be fashioned into anything as enduring as “Hamlet.” But they can make us cling to the beauty of the world, newly reminded of how fleeting it all is. How fleeting we all are.

I spent the end of 2025 immersed in the lush language and visual palette of “Hamnet,” just as online algorithms, anticipating the season of fruitless goals, fed me promises of transformative weight-loss plans and exercise routines and methods for achieving a life that is calmer/happier/better-organized/fill-in-the-blank-here.

The repeated collision between commercial manipulation and high art became almost comical. We’re here such a short while, I kept thinking. Aren’t most of us basically OK as we are? Will it matter in 400 years if we’re a little overweight, a bit out of shape, somewhat disorganized, definitely too distracted?

Sure, it’s facile and shallow to draw any simplistic moral from a story as magnificent as “Hamnet,” never mind a moral related to the futility of New Year’s resolutions. Nevertheless, wouldn’t it make more sense to skip the self-improvement resolutions this year and look instead for great works of art to surrender to? To let our hearts keep breaking as the fleeting world makes us just a little more human?

Because the rest, as Shakespeare knew, is silence.

Margaret Renkl, a contributing Opinion writer, is the author most recently of “The Comfort of Crows.” Her new book for children is “The Weedy Garden.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post A Case for Beauty in a Fleeting World appeared first on New York Times.