PARIS — Life, says Merry Levov, the troubled young character at the center of Philip Roth’s “American Pastoral,” “is just a short period of time in which you are alive.” More than any other artist I can think of, Gerhard Richter confirms the essential truth of this bleak, Beckettianworldview.

Why, then, do so many of us revere him?

Perhaps the most notable thing about the 93-year-old German artist, who is the subject of a retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, is that he refuses to wring meanings from life that aren’t there.

We know they’re not there because history and unimaginable loss have taught us they’re not there. The very search for meaning, his work suggests, is a histrionic response to reality, and, to that extent, in bad taste.

Yet, despite this, Richter presents us, again and again, with works of ravishing beauty. His abstract paintings, in particular, evoke sensations of speed and teeming plenitude. They shimmer and pulse like Ottoman silks, pixelated digital screens or sunset ripples on a wind-ruffled lake.

The paint’s smoothed-out striations are punctuated with rips, like stockings stretched past their breaking point, each tear in the paint uncovering complex color harmonies beneath. Richter’s surface textures alone are a marvel: They are to Gustave Courbet’s cakey, palette knife effects as the sonic world of late Radioheadis to the Beatles.

But unlike the paintings of America’s abstract expressionists, which benefited from a hopped-up rhetoric of authentic self-expression, Richter’s abstract paintings have a deliberately random, mechanical quality. One painting might be slightly more or less beautiful than another, but they are basically interchangeable. Lacking any convincing claim to uniqueness, they routinely slump back into nihilism, numbness, banality.

Richter is the most sensitive and cerebral of artists. Like Jasper Johns, with whom he shares a fascination with mirroring, duplication and loss, he has often been seen as cool and impervious, but he is deeply humane. Unlike his German contemporaries Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz, he is against melodrama. His natural modes are modesty, fastidiousness and a kind of prolonged existential hesitation.

The visual correlative to this hesitation is the blur for which Richter is best known. In his photorealist paintings, he achieves this blurry effect by feathering the yet-to-dry surface with a dry brush.

In his abstract paintings, he achieves it by dragging a long rubber squeegee attached to what looks like a steel girder across large canvases preloaded with paint.

The two effects, clearly related, suggest degrees of veiling or erasure. The unpredictability baked into the abstract works’ making reveals Richter’s indebtedness to Marcel Duchamp, modernism’s ringmaster of randomness. (Richter’s “Ema (Nude on a Staircase)” is his homage to Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase.”) He is also a cousin to Duchamp’s American, chance-loving progeny: John Cage, Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly and Andy Warhol.

“Somehow the tools do what they want,” Richter said in a 2011 documentary. “I would have done it differently.”

If the process behind the photorealist paintings is more deliberate, the choice of subjects is not. The images are chosen from “Atlas,” Richter’s archive of random-seeming photographs, which range from family snapshots to sensational news.

In the resulting paintings, it is as if the blurred subjects are at risk of sinking back into a repressed or forgotten past, which may, in turn, make us care for them more. Richter speaks of his images in terms of doubt and perseverance. They may hang on the walls of museums, but the impression they give is of hanging on by a thread.

Something like that is presumably how much of Richter’s early life must have felt.

Richter, born in Dresden in 1932, was obliged as a boy to join the Pimpfen, a feeder organization for the Hitler Youth. He was in a village about 60 miles from Dresden when it was firebombed in February 1945.

In the war’s aftermath, shame and denial permeated German life — and Richter’s life in particular. His aunt Marianne, diagnosed with schizophrenia, had been sterilized, then starved to death at the mental hospital run by Richter’s father-in-law. His uncle Rudi, with whom he was close, had been killed on the Western Front in 1944. Richter’s father, drafted into the military in 1939, became a prisoner of war in 1945 and was barred from returning to his teaching profession because he had been a (compulsory) member of the Nazi party.

Richter was given his first camera in 1945. So it comes as little surprise that he became curious about how photographs capture — and, at the same time, fail to capture — intimate aspects of family life. Richter would address this decades later with his gently blurred photorealist paintings of himself, as a child, in the arms of his murdered aunt; of his wife reading and nursing their baby; and of his 11-year-old daughter poignantly turning away.

But he has always been equally concerned with how photographs simultaneously bear witness to and repress the real experience of historical catastrophe. His most celebrated paintings begin with photographs of death and disaster, then submit them to doubt, blur, abstraction, redaction.

Near the end of the show in Paris, for instance, is a gallery filled with four huge, abstract paintings that draw on — and conceal behind mechanically applied paint — the clandestine photographs of a gas chamber and mass burials at Birkenau. The photographs themselves, which were taken by Jewish Sonderkommandos(the negatives were smuggled out in a tube of toothpaste), hang on the farthest wall from the entrance.

The display is a statement about the necessity of historical memory — but it’s also, of course, about the impossibility of representing the unthinkable.

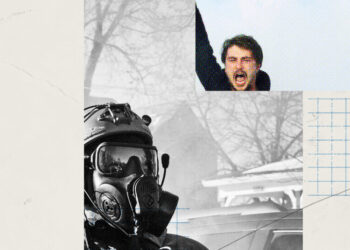

Another gallery earlier in the exhibition gathers the works in “October 18, 1977,” Richter’s 1988 series of blurred, photorealist paintings of members of the far-left Baader-Meinhof terrorists — including images of their group suicide in prison in 1977. These black-and-white images are presented with no editorializing, no explanation.

The show also included Richter’s small, paint-veiled image of a hijacked plane hitting a New York skyscraper in September 2001.

But these strangely reticent stabs at old-fashioned history painting are relatively unusual in his oeuvre. They are surrounded by imagery that can best be described as humdrum, shopworn and, above all, arbitrary — images of candles (one even featured on the cover of an iconic Sonic Youth album), fighter jets, flowers, cities and pleasant-enough European landscapes, all based on photographs, all gently blurred.

In communist East Germany after the war, Richter received rigorous technical training at the Dresden art academy. Modern art was off-limits. Everything from impressionism on, Richter was taught, was marred by bourgeois decadence. (The Nazis had characterized the same art as “degenerate.”)

Richter enjoyed some success as a painter of socialist realist murals. In 1959, he was permitted to travel to Paris and then to Kassel in West Germany to see the Documentaexhibition. This was his first exposure to avant-garde Western art, and it upended his world. Two years later, having defected to the West, he reenrolled in art school in Düsseldorf.

In West Germany’s thriving capitalist economy, Richter was inundated by imagery in the forms of advertising, photography, film and other mass media. He became interested in pop artists, and from 1963 to 1971 he established, with two friends (including the protean Sigmar Polke), a mini-movement, sardonically dubbed “capitalist realism.”

Emulating Warhol’s appropriation of news photography and advertisements, along with his reproduction-based techniques, Richter converted American pop art’s deadpan yet secretly gleeful acceptance of everything into images characterized by a pervasive, postwar European numbness.

Against Warhol’s ebullience (the flowers, the cows, the celebrities!), Richter’s paintings are the aesthetic equivalent of ashes in the mouth. They were once something. But at some point they were burned up, carbonized. You look at them, and absolutely nothing comes back.

There are, however, exceptions. Some of Richter’s human subjects, in particular, can appear alive, or almost alive. Blurry, haunted, they are like ghosts yearning (it can seem — but this is clearly my projection) to achieve a fullness of being that is being denied them.

What, exactly, is denying them this fullness of being? Is it simply the passage of time — the inevitable passing of all that we saw and cared about? Has it to do with the difficulty of ever truly bearing witness to historical trauma? Or is it something sick at the heart of our fanatical culture of image-making?

I can never decide. But I return to the paintings’ beauty. Richter’s best works resonate like a sustained, shimmering chord made up of dozens of tones and quarter tones and subtly shifting timbres. To spend time with them is to sit inside this chord, listening as it shifts almost imperceptibly from white noise to exquisitely calibrated symphonic bliss and back again.

After he painted his “October 18, 1977” series, Richter wrote the following statement: “Deadly reality, inhuman reality. Our rebellion. Impotence. Failure. Death. That is why I paint these pictures.”

Such is this artist’s refusal to offer reassurance. But if there is hope in Richter’s work, it derives precisely from his allergy to false hope. It comes from accepting the reality of our world, in which beauty routinely erupts without goodness or meaning anywhere in sight.

And hope emerges, too, from the haunting emotion produced by a handful of his best pictures. This emotion, which is set off and enhanced by the randomness of all that surrounds them, is akin to wisps of steam coming off a body emerging into cold air after having bathed, however briefly, in love.

“Gerhard Richter” is at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris through March 2.

The post The ravishing beauty and (almost) nihilism of Gerhard Richter’s art appeared first on Washington Post.