A Maryland commission recently concluded that state leaders and institutions were complicit in 38 lynchings and the widespread racial terror that followed the Civil War — and said current leaders should atone with cash payments to descendants of the victims.

The recommendations set Maryland on a course to undertake a politically complex debate on reparations against the backdrop of President Donald Trump’s criticism of institutions that he says are too fixated on slavery. While Trump called museums that document African American history, such as the Smithsonian Institution, “essentially thelast remaining segment of ‘WOKE,’” Maryland’s commission finished work on what it called the nation’s only government-backed effort to hold itself accountable for lynching.

“The fires of resentment, mistrust, and division that burn in our communities today were lit by torches of racial terror centuries ago, and we cannot extinguish those fires by ignoring how they started,” the commission’s report said.

The commission spent six years and 630 pagesdocumenting how law enforcement, politicians, judges and media contributed to either the deaths, the lack of justice for victims or the systemic racism that empowered White mobs to act with impunity.

Victim by victim, the Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s sprawling final report details that complicity. It recommends $100,000 for every surviving descendant of lynching victims and $10,000 for descendants of people who lived in communities terrorized by lynchings, among 84 suggestions for how Maryland could atone for the extrajudicial killings and the racial terror created in Black communities.

“The trauma inflicted by these crimes, often carried out as public spectacles, reverberated through generations. Communities were left to live in the shadow of violence without recourse, justice or recognition,” the report said.

No perpetrators were ever held accountable in any of the deaths, which occurred between 1854 and 1933. Some included mutilations or burnings. Photos of some lynchings were made into postcards as souvenirs. All killed were Black men or boys; one was 14 years old.

Three commissioners described their report and its unvarnished retelling of the brutal truth about racial terror as a form of resistance against the attacks on diversity, equity and inclusion efforts the president has encouraged.

“It’s not just a form of resistance, but it is remaining faithful to the truth,” said Nicholas Creary, a Bowie State University professor and commissioner who helped build the historical record for the report.

“Lynching was not just the murder of an individual,” he said. “It was a communal act, and it was a message crime, intended to silence African American communities and to ensure that they — to use the old colloquial phrase — that Black folks stayed in their place.”

Maryland’s newly elected House speaker, Joseline A. Peña-Melnyk (D-Prince George’s), sponsored the law to create the lynching commission in 2019, when she was a delegate, and has championed its mission.

“This is just the beginning, and there’s a lot of work to be done,” Peña-Melnyk said in an interview.

The law granted the commission subpoena power and resources to collect oral histories, documents, testimony and existing local research, as well as hold public hearings and hire genealogists to track down the full truth about the state’s brutal history.

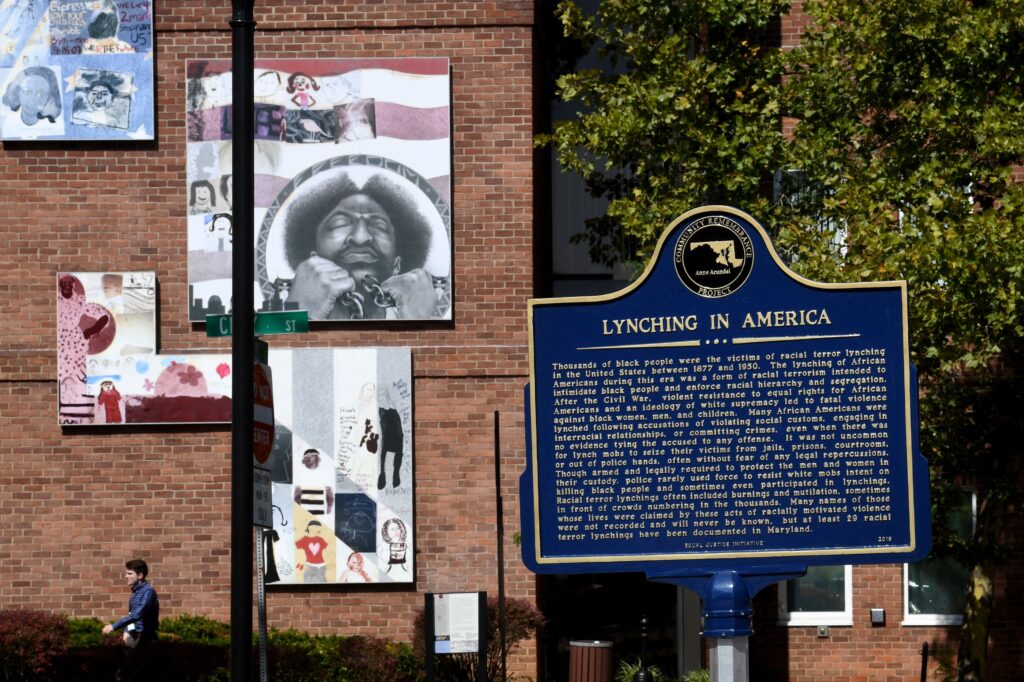

Maryland is among eight states outside the Deep South where lynching was common albeit less frequent, according to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative.

More than 4,000 lynchings happened in 12 Southern states between the Civil War and World War II, the EJI report found, with the most — 654 — documented in Mississippi. Another 361 were in Alabama, 549 in Louisiana and 84 in Virginia. Historians have struggled for years to pinpoint how many Black people died in lynchings. As recently as 2020, researchers documented an additional 2,000 lynchings that had not be included in their previous tallies. The current estimate stands at 6,500.

Maryland Gov. Wes Moore (D), a potential 2028 presidential contender and the only Black governor of a U.S. state, ran on a “Leave No One Behind” platform in 2022 that included closing the racial wealth gap and dismantling systems of racial oppression.

This year, he vetoed a bill to study reparations for the legacy of slavery, saying that the enduring racial disparity in Maryland had been sufficiently studied and that he wanted to enact policies, not study them.

The General Assembly overrode his veto last month, on the same day the House of Delegates elected Peña-Melnyk as its new leader. The commission details 84 specific policies, divided into nine categories, to remedy the injustice. It’s now working on turning those into legislation for Peña-Melnyk to consider championing in the upcoming General Assembly session.

“Every Black person who modified their behavior out of fear, who lost property to White mobs, who was denied economic opportunity, who fled their community to protect their family, was a victim of this system,” the report said.

The proposals range from the cash compensation to strengthening current due-process protections, law school scholarships, integrating the history of racial terror into school classrooms, and an array of “symbolic reparations” that include apologies and memorials.

The governor’s office has so far been noncommittal about all of them.

“Given the scope of the report, it would be premature to commit to specific proposals before completing a full review,” spokesman Ammar Moussa said in a statement.

But, Moussa said, “Gov. Moore believes the work of repair demands urgent, measurable action — and his administration will keep delivering results that expand opportunity and close gaps that have held Black Marylanders back for generations.”

Senate President Bill Ferguson (D-Baltimore City) said through a spokesman he looks forward to reviewing the recommendations, and “recognizes the painful and necessary work” the commission undertook.

The $100,000 and $10,000 amounts of the proposed reparations are drawn from history: They represent the present-day value of compensation proposed in anti-lynching bills Maryland state lawmakers drafted but did not approve in the 1930s.

David O. Fakunle, commission chair and an assistant professor at Morgan State University, said that while the cash reparations constitute the most eye-catching recommendation, it’s not the most important.

“The number-one recommendation is to tell the truth,” Fakunle said.

“It’s the story that nobody wants to talk about. We’ll talk about slavery, Jim Crow, all that stuff before we want to talk about lynching. There’s a reason: because it’s heinous. It’s the worst of humanity.”

Fakunle said that over the course of six years, the commission notified some people of the fact that their ancestors had been lynched, and heard from descendants of people who had been perpetrators and wanted to make amends. Institutions, such as the Baltimore Sun, acknowledged the role they played in creating a culture that allowed lynching to fester, he said.

“It costs nothing to apologize,” Fakunle said. “If you truly believe that the unnecessary taking of lives, regardless of who they are, without due process is wrong, is immoral, is unethical, is against the law, there has to be some form of atonement.”

The commission uncovered a case that had not been previously catalogued on the Maryland State Archives’ Legacy of Slavery.

On the state’s Eastern Shore, in roughly the same region and era in which Harriet Tubman was conducting the Underground Railroad, leading enslaved people to freedom in the north, a 14-year-old enslaved boy named Frederick Pearce was accused of attempting to rape a 14-year-old White girl after pulling her off a horse in 1861.

A White mob later lynched him from a tree at the site of the alleged incident, and while three newspapers reported on the killing, “the newspapers did not question whether Frederick Pearce committed a crime,” the report said. “The newspapers celebrated the lynching of Frederick Pearce.”

One headline said that “the residents of Cecilton upon hearing of the outrage, caught the negro and hung him to the nearest tree.”

The report acknowledged that most of the lynching victims were similarly accused of crimes, though it noted that throughout history many were targeted on spurious charges. “We honor these victims not to endorse alleged crimes, but to affirm that every person — regardless of accusation — deserves due process, a fair trial, and protection from mob violence. In so doing, we honor the rule of law itself,” the report said.

The commission researched 42 killings but excluded four. One case assigned to Maryland actually happened outside its borders, Fakunle said, and others didn’t meet the definition of a racial terror lynching, although a hanging may have occurred.

As the commission did its work, Maryland’s then-governor, Larry Hogan (R), posthumously pardoned 34 Black lynching victims in 2021, the first country’s first systemic pardon of all known lynching victims in a state.

The Eastern Shore accounted for more than a third of Maryland’s documented lynching cases.

“What set the Shore apart was not just the frequency of these acts, but the broad complicity of local institutions — law enforcement, churches, schools, political leaders — and the deliberate suppression of Black autonomy through both formal segregation and extralegal violence,” the report said.

One of the most extensively documented extrajudicial killings was the death of Matthew Williams, 23, in 1931. Williams was accused of shooting and killing his boss, Daniel J. Elliott, owner of a box factory, but there were conflicting accounts of the alleged crime.

At the scene where Elliott died, Williams had also been shot. A mob took him from his hospital bed in Salisbury and lynched him in front of the courthouse, with several of his toes cut off as souvenirs, the report said. Williams’s body was dragged behind a truck to a Black neighborhood, tied to a lamppost and doused in gasoline, burning while firefighters looked on, the report said. A sheriff dumped his body in a field outside of town. A second, unidentified man is believed to have been killed by the same mob.

“It was the lynching of [an] entire community,” Charles Chavis, vice chair of commission and author of a book on Williams, said in the report. “You had African Americans who were running, jumping in the river, individuals who were just running for their lives. It was a night of terror. It was not one targeted incident where the individual was obtained, and it was over. The entire black community was put on notice.”

The report shares two of the surviving — and conflicting — explanations about what transpired before Elliott’s death.

One alleges that communists had stoked local outrage over wages, and that Williams had shot his boss after an argument over a raise. This account says Williams then shot himself in the chest, and then was shot a second time when Elliott’s son saw Williams trying to flee the scene. An alternative contemporary telling of the crime says Williams had lent Elliott’s son money, and the son shot them both after Williams asked his boss to help him recover it. According to the report, Williams had worked in the family’s business for nine years and earned 15 cents an hour. That’s about $3 an hour in today’s dollars.

It was the first lynching in Maryland in two decades, and the governor, Albert Ritchie, called for prosecution against the mob and an investigation into what happened.

A grand jury heard from 124 witnesses but did not identify any member of the mob, and no one was indicted in the killing.

The post Maryland studied its complicity in lynchings. Are reparations next? appeared first on Washington Post.