I was blown away last summer by an exhibition of Gabriele Münter’s paintings at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. Here was an artist, born in Berlin in 1877, who channeled the lessons of 20th-century expressionism — including the bold colors of Fauvism — while still going strong into the mid-20th century, long after those explosive discoveries by modernist painters had waned. Her paintings looked incredibly contemporary, like they could have been made today. It was easily one of my favorite exhibitions of 2025.

The current show at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, titled “Gabriele Münter: Contours of a World,” isn’t quite as electrifying. It focuses on her early alliances and influences rather than her breakout use of color, and it is presented in three galleries over two tower floors, so you have to leave the exhibition, walk through Rashid Johnson’s plant-filled showcase in the rotunda and re-enter the Münter to see it all. However, it’s a good survey that continues the important work of showcasing women and other marginalized figures who contributed to European modernism.

And with some 50 paintings, it is also a fine introduction to Münter, an overlooked founder of the avant-garde group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). Known for using color and line for expressive purposes, they paved the way to abstract painting — including New York’s own abstract expressionists.

“Contours of a World” also includes a generous selection showcasing Münter’s youthful foray into black-and-white photography from the late 1890s and early 1900s, suggesting that she might have carved out a robust career in that medium if she had chosen it over painting and printmaking. (The show is curated by Megan Fontanella and Victoria Horrocks.)

It’s fitting that this show is at the Guggenheim because Münter’s romantic and professional partner from 1903 to 1914 — the years when great strides were made in German painting — was Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), whose pioneering abstract paintings formed the core of the museum’s permanent collection after its opening in 1939. He often overshadowed Münter’s contributions; the museum’s founder, Solomon R. Guggenheim, eventually bought more than 150 Kandinsky paintings, while the Guggenheim owns one painting by Münter, “Snow-Covered Fir Tree” from 1933, which was purchased in the 1980s.

Born into a liberal, upper-middle-class family, Münter at first received private art lessons, since women were not allowed to enroll in German art academies until 1919. In 1902, she took an evening life-drawing class with the Russian-born Kandinsky, who would soon become her romantic partner. (Kandinsky was married to a cousin; they parted in 1911.)

Münter and Kandinsky spent 14 months in Paris in 1906 and 1907 absorbing the lessons of radical French painting, particularly around color and flattening the representation of people, objects and landscapes on the canvas, instead of treating a painting like a Renaissance window looking into deep space. After returning to Germany, Münter and Kandinsky, along with Franz Marc, founded Der Blaue Reiter in 1911.

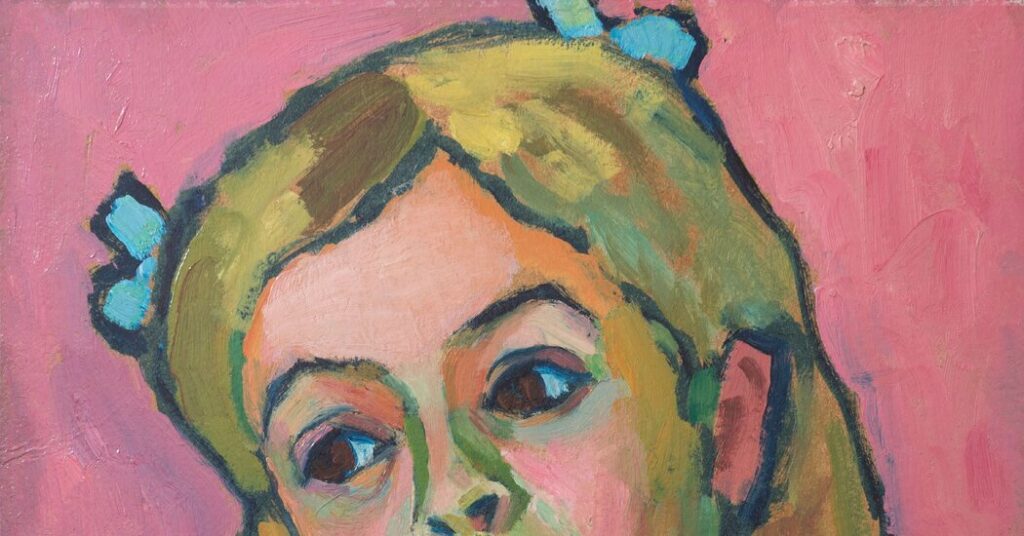

Münter’s best paintings here, like “Head of a Young Girl” (1908), with its bold contrasts of pink and red, show the impact of Fauvism, particularly Matisse, and the Nabis painters (from the Hebrew word “Nebiim,” or prophets) such as Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who were responding to Gauguin and Cézanne. When she lived in Paris in 1906, Münter had neighbors who collected Fauvist paintings and she attended the salons of Gertrude Stein, which were populated by artists, writers, collectors and art dealers.

Slightly later works like “Kandinsky and Erma Bossi” (1910) and “Man in Armchair (Paul Klee)” (1913) feature members of Münter’s artistic milieu and depict the sitters in a flatly drawn, almost naïve style. Klee, who would go on to teach at the Bauhaus and inspire generations of abstract and spiritually inclined artists, hardly needs an introduction. Bossi was another talented woman working in an expressionist vein, with Van Gogh-style expressive drawing and deep, moody coloring.

After her acrimonious split with Kandinsky, who had moved back to Moscow and married another woman without telling her, Münter focused on drawing for nearly a decade. She also kept her head down during the Nazi regime, exhibiting in Nazi-curated propaganda shows like “The Streets of Adolf Hitler in Art” (1936) but also hiding her collection of modern art in the basement of her house in Murnau, outside Munich — a gathering place for the Blue Rider group and now a museum. It might have been considered “degenerate” by the Nazis and confiscated.

“The Blue Lake” (1954), a much later work by Münter, belongs to that period that caught my attention in Paris. Here, she has come out the other side of World War II and depicts a landscape with acid hues. Long after the period of Fauvism, Münter was still thinking about how color could be used to enhance her subjects. There is a resolution in these late paintings: They don’t feel like German expression as much as they seem to absorb the glow of electric lights — or even of television, which predicted the illuminated screens of computers, tablets and smartphones.

And then there are the photographs. From 1898 to 1900, Münter visited her mother’s relatives who had migrated to the United States. Displayed in a different Tower gallery from the paintings, suddenly we are confronted with images of people in Missouri, Arkansas and Texas. Taken with a mass-marketed No. 2 Bulls-Eye, her landscapes and portraits show a keen eye for composition and scenes she wouldn’t have witnessed in Germany. “Willie [William Graham] reading on the floor of his bedroom, Guion, Texas” from 1900 is a lovely gelatin silver print that recalls modernist photographers like Alfred Stieglitz or Jacques-Henri Lartigue, who also photographed his family.

“Three boys, probably St. Louis, Missouri,” photographed in July to September 1900 (and printed in 2006 to 2007), shows us three laughing youths in a spontaneous moment of joy, while “Three women, Marshall, Texas” was taken on Juneteenth — Emancipation Day, June 19, 1900, and captures a group of elegantly dressed Black women, two of whom look directly into the camera lens.

This, of course, is another world, far from Murnau, and, theoretically, the concerns of European painting. When Münter returned to Germany, she followed a different path. And yet, you wonder what did Münter bring with her from America, and photography, to her painting? Perhaps a sensitivity to composition, to interiors and landscape and light, and an expanded view of the world’s people.

You also can’t help wonder, while gazing at Münter’s photographs, what if she had remained in America and become a photographer? The art world, including the Guggenheim itself and its grounding in Kandinsky’s circle, might look very different today.

Gabriele Münter: Contours of a World

Through April 26, 2026. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue; 212-423-3500, guggenheim.org.

The post Gabriele Münter, an Overshadowed Pillar of Modern Art, Gets a Spotlight appeared first on New York Times.