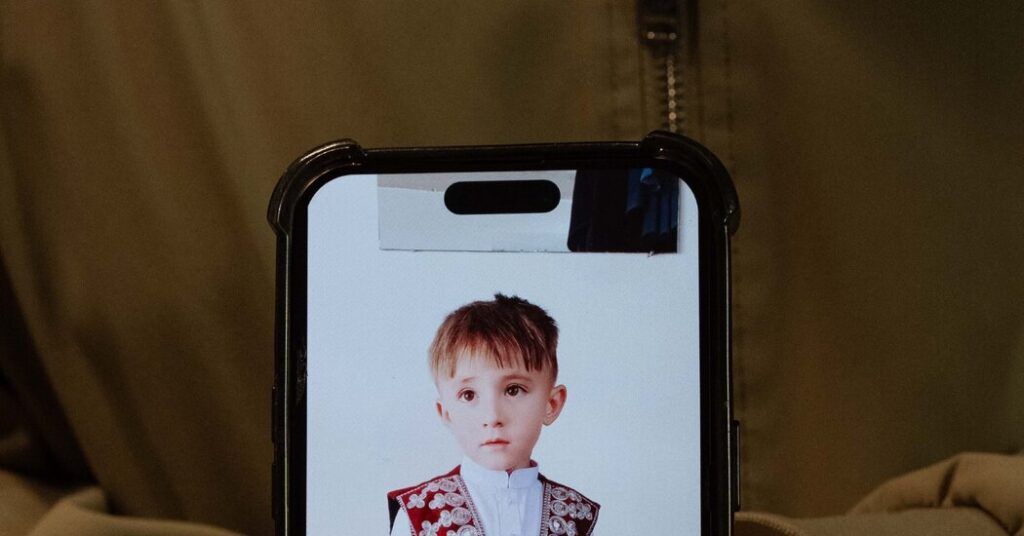

Husna Hashemi keeps photos on her phone from the day more than three years ago when she handed her infant son, asleep and swaddled in blankets, to her husband’s parents and brother in a city park in Kabul.

She didn’t want to leave — even now, speaking in Dari through an interpreter, she wept as she talked about returning to Afghanistan to be with her youngest child. But her husband, Sayed Rasool Hashemi, had worked for years with the American military, and after the U.S. government fled Afghanistan, the Hashemis faced a terrible choice: Stay and risk everyone’s lives or leave their newborn behind.

“I did not want to go without him,” Ms. Hashemi said. “What kind of mother does that?”

The Hashemis’ story, told from their neat, snug suburban apartment in Beaverton, Ore., where the immigrants are building new lives, holds twists and bureaucratic dead ends that span two presidential administrations and would make Franz Kafka proud. It’s capped, for now, by President Trump’s near-total blockade on Afghan immigration. In its infuriating absurdity is a metaphor of sorts for the long war’s chaotic end.

On a recent evening, the laughter of the Hashemis’ two older children broke the quiet every now and then, but their youngest child’s voice remains missing from their attempt at the American dream.

“It’s just so stupid,” said Brian Torres, a family friend. “So stupid and cruel.”

Sayed Anas Hashemi was just a month old, with no visa or passport, when his parents were forced to leave him behind. Efforts to bring him to the United States have lurched onward, but an attack on two U.S. National Guard soldiers near the White House in November, and the charging of an Afghan immigrant who had also worked for the United States, has left any reunion on hold.

“Every time we get so close, then something happens,” Mr. Hashemi said. “Now, we just don’t know.”

Mr. Hashemi was in his late teens when he began working for the U.S. government in 2004, first doing odd jobs for the military, then serving as an interpreter for American contractors. He considered it the right thing to do — he remembered life as a child under the Taliban as violent and frightening — and an economic opportunity, particularly after he married and started a family.

“They said they will take care of us,” he said of his employers. “I heard that many times.”

When President Joseph R. Biden Jr. set the final timeline for the American withdrawal from Afghanistan, culminating in the frenzied departure from Kabul in August 2021, Mr. Hashemi took his family into hiding.

“Everybody was scared,” Mr. Hashemi said.

The risks to Afghan citizens seen as cooperating with the United States were apparent enough that the United States established an office within the State Department — the Coordinator for Afghan Relocation Efforts, or CARE — and offered a special immigrant visa for Afghans deemed likely to face Taliban reprisal. The system, crafted by the Biden administration, was overwhelmed from the start.

Mr. Hashemi began the visa application process even before the Americans left and waited more than a year for the paperwork allowing him to leave for Qatar, the first stop for many Afghans fleeing to America. During that interlude, Ms. Hashemi became pregnant with their third child, and Sayed Anas was born in September 2022.

The family’s paperwork came through one month later. The infant did not have a passport and hadn’t been included on the family’s visa applications because he hadn’t been born. They spent almost four months in Qatar, but Sayed Anas still didn’t have the proper documents when the rest of the family received permission to fly to the United States in February 2023.

They thought their son would be allowed out in months, not years.

Their friend Mr. Torres, a former middle school teacher, started volunteering with a refugee resettlement group after listening to a ride-share driver in Washington, D.C., recount his story about leaving Afghanistan so his children could get an education. The Hashemis were Mr. Torres’s first assignment. He thought the work meant helping with the basics of building a life in a new country, in the suburbs of Portland, Ore., such as how to schedule doctor’s appointments or buy car insurance.

But every conversation with the Hashemis came back to the same reality, that their life in the United States couldn’t truly begin until they had their son.

Mr. Hashemi initially tried to work through CARE, but by the time the boy’s passport arrived last year, the agency was overloaded and understaffed. Calls and emails went unreturned. Then, the Trump administration closed the office earlier this year, part of a broader State Department restructuring that included deep staff cuts.

Even before that, the family’s lawyer, Gabe Espinal, suggested they work directly with a U.S. embassy in Central Asia or the Middle East. But different countries, even different U.S. embassies, have their own policies about when and how they process visa applications or whether they’ll even work with Afghan nationals. Many that do remain are plagued by backlogs.

The Hashemis secured a visa interview appointment for Sayed Anas at the U.S. Embassy in Qatar but with four days’ notice, nowhere near enough time to get him there. Officials at the U.S. Embassy in Tajikistan told them to fill out an online visa form for Sayed Anas. For months, they could not get the link to work.

“I don’t want to call this a comedy of errors because none of it is funny,” Mr. Torres said. “But at every step, something seemed to go wrong.”

This past fall, a reunion felt close. The embassy in Tajikistan told Mr. Hashemi and his lawyer that if they could get Sayed Anas to Dushanbe, the country’s capital, the embassy would process his case.

Then came the National Guard attack.

President Trump declared that “every single alien who has entered our country from Afghanistan” during the Biden administration must be re-examined. The State Department has frozen visas for Afghans, though the U.S. government website about the presidential proclamation barring Afghan nationals notes that limited exceptions may be made for people younger than 8 with special immigrant visas.

The White House referred questions to the Department of Homeland Security. A spokeswoman for the department did not respond to requests for comment.

Mr. Espinal thinks the evolving federal policy could allow Sayed Anas into the United States, but he’s not certain and has struggled to find someone who can answer his questions. The family also doesn’t know whether Mr. Hashemi, who hopes to fly to Asia to take his son through the final steps in the process and bring him to the United States, would be allowed back in if he made the trip. The State Department and the White House did not respond to requests for comment.

“This family could be reunited in three months,” Mr. Torres said. “Or it could be another three years.”

Meantime, their older children, now 11 and 8, are thriving in school. Mr. Hashemi, who said he was not angry at the U.S. government, has a job with a company that makes gun sights and has created a small support group for other Afghan refugees in Oregon. Ms. Hashemi is taking English classes with other Afghan women but struggles to focus on anything but her missing child.

“She is sick all the time,” Mr. Hashemi said. “She cannot stop crying.”

They’ve watched Sayed Anas grow from a baby to a boy through a screen. The child, now 3, knows who his parents are thanks to regular WhatsApp calls and that they’re trying to bring him to the United States. Like them, he just doesn’t know when that will happen.

“All the time when we call, he says, ‘I want to come there, I want to see your house,’” Mr. Hashemi said. “My brother tells him that I will come get him on a plane. So sometimes he tells me, ‘I see your plane today.’ He sees planes, and he thinks we are coming to take him.”

Anna Griffin the Pacific Northwest bureau chief for The Times, leading coverage of Washington, Idaho, Alaska, Montana and Oregon.

The post 3 Years After a Toddler’s Parents Fled Kabul, a Reunion Is Still on Hold appeared first on New York Times.