The dream of return has animated the Palestinian struggle for more than seven decades. In 1948, more than 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes during the violence surrounding the creation of Israel. That foundational trauma — known to Palestinians as the Nakba, or “catastrophe” — continues to ripple across generations and borders.

Palestinian refugees, in neighboring Arab countries and across the world, claim a right to return to their ancestral homes. They see a historic injustice unaccounted for and an ongoing occupation that hems their people into ever-smaller spaces with fewer rights. Israel sees an existential threat to its identity as a Jewish state. The resulting conflict has become one of the world’s most intractable, erupting with fresh ferocity on Oct. 7, 2023. That’s when Palestinian militants led by Hamas, the Islamist movement that has ruled Gaza since 2007, stormed southern Israel, killed about 1,200 people — many of them civilians — and took 251 hostage. In response, Israel unleashed one of the most ferocious assaults in modern warfare on the Gaza Strip, The Washington Post has previously reported based on visual forensic analysis, sparking fears among Palestinians and in Arab countries of another Nakba.

Today, the global Palestinian population has reached close to 15 million, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Half of them live outside of historic Palestine, mostly in Arab countries. More than a third are still registered refugees. Many Palestinians trace their family history through multiple displacements. Exile, and a longing to return to the homeland, is the thread running through contemporary Palestinian identity, culture and politics.

Israel’s war in Gaza is this generation’s defining trauma. It has killed more than 70,000 people, erasing entire families, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, which does not distinguish between civilians and combatants but says the majority of the dead are women and children. The vast majority of Gaza has been flattened by the bombardment, rendered unrecognizable. Some 1.9 million people — about 90 percent of the population — are internally displaced. Hunger remains widespread. A U.N. commission said in September that Israel has committed genocide in Gaza, a charge Israel denies.

A fragile ceasefire has held since October. The United States is pushing an ambitious plan for a new order in Gaza, one that it says will keep Palestinians there, but it remains unclear if it can get buy-in from the warring parties and foreign countries. Far-right politicians in Israel, meanwhile, continue to call for the mass expulsion of Palestinians from Gaza and the annexation of the West Bank. Opposition by Arab countries has so far prevented the mass displacement of Palestinians from the Gaza Strip. Still, more than 100,000 Palestinians have trickled out over the course of the war. In Egypt and farther afield, they are caught between trying to move on and hoping to move back. At this juncture, it remains unclear whether their ranks will shrink or swell.

Life as second class

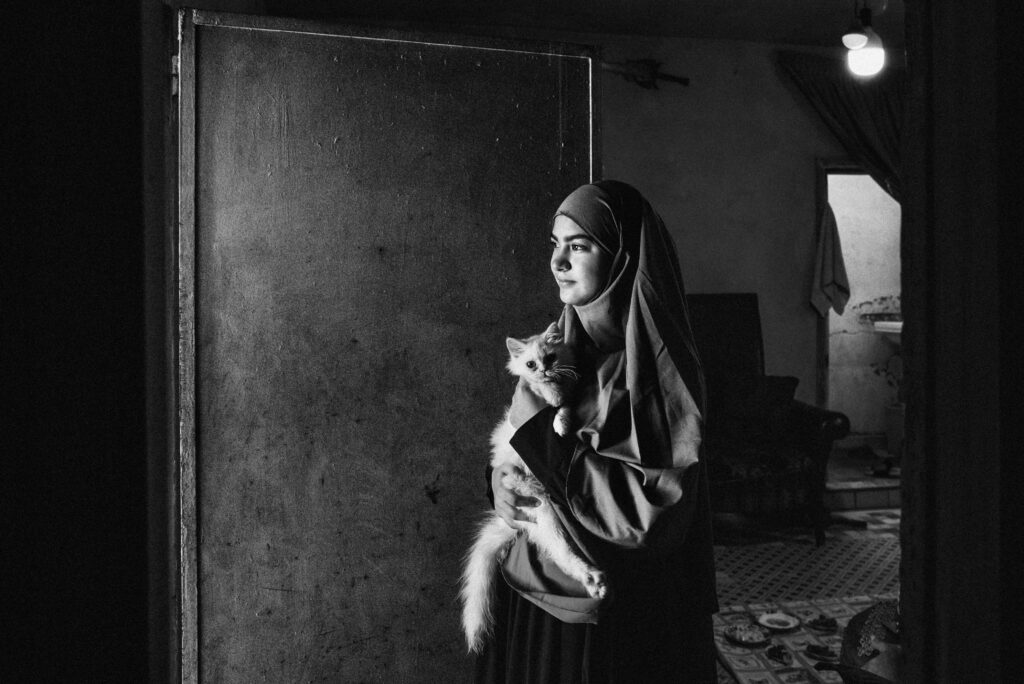

For Palestinians in Lebanon, life is precarious and tightly circumscribed. Most of their families came to the country after fleeing or being expelled from what became Israel in 1948. The United Nations estimates that more than 200,000 Palestinians reside in Lebanon — about half of them in the country’s 12 refugee camps. They are barred from practicing many professions and from owning homes. Poverty is high; legal rights are lacking.

In Shatila, a dense refugee camp in southern Beirut, the pride and the trauma of being Palestinian is passed through generations. The elderly remember their flight from Palestinian territories and the violent, transient years that followed. The middle-aged are scarred by the infamous massacre there in 1982, when Israeli-backed Christian militiamen rampaged through the camp, killing at least 700 and potentially as many as 3,500 people. The young, excluded from Lebanese society, seek escape — by sea to Europe, or through drugs.

Fresh wounds of exile

In Egypt, the newest wave of Palestinian exiles live in limbo. Since the war in Gaza began in 2023, the Egyptian government has firmly opposed the mass displacement of Palestinians to Sinai, fearing this would amount to ethnic cleansing of Gaza and undermine Egyptian national security. Still, tens of thousands of Gazans arrived in the country during the first months of the war — either as medical evacuees or by paying a hefty “coordination” fee to an Egyptian company to cross the border. After Israeli forces seized the Gaza side of the border in May 2024, that escape route largely shut.

Once in Egypt, Gazans were mostly given 45-day tourist visas. Some with connections to other countries moved on; many stayed in Egypt, existing in a legal gray area. They can’t enroll their kids in public schools or apply for formal work. They have tried to begin to heal and to settle into new rhythms. But Gaza and the suffering of those left behind are always on their minds. From Cairo, Palestinian artists have created and showcased works that trace life and war in the troubled enclave.

An identity straddling the border

Jordan, which borders the West Bank and controlled it before the 1967 war, has long had an intimate, and complex, relationship with Palestinians. Jordan gave citizenship to most Palestinian refugees displaced from their homes in 1948. (Those who came later from Gaza have fewer rights.) Three-quarters of a century later, more than 2 million Palestinian refugees are officially registered with the U.N. in Jordan — but scholars estimate the actual proportion of people of Palestinian descent to be much higher, perhaps more than half of the population.

Unlike Palestinians in Lebanon, which does not have diplomatic relations with Israel, some Palestinians in Jordan are able to travel to the West Bank to visit relatives there. Their identity straddles the heavily securitized border: They have integrated into the society and economy of Jordan, but they often display their Palestinian heritage loudly and proudly. To the Hashemite monarchy, though, Palestinians could pose a threat to its traditional Jordanian power base. That’s one reason King Abdullah II firmly rejected President Donald Trump’s call for Jordan to accept Gazans in large numbers during the current war.

About this story

Photography by Lorenzo Tugnoli. Text by Claire Parker. Editing by Alan Sipress and Olivier Laurent. Copy editing by Jeremy Hester.

The post Portraits of a Palestinian diaspora appeared first on Washington Post.