Here’s a quick quiz about some cultural icons on the verge of experiencing a kind of rebirth:

1. What was the original storyline of the Dagwood and Blondie comics? 2. What was Blondie’s maiden name? 3. In her original incarnation, what animal was Betty Boop?

Those characters all date from 1930, which means that on New Year’s Day 2026 they lose their copyright protection — or at least some of it — and enter the public domain. That means that, creatively speaking, they’re available for anyone to copy, share, slice and dice, reconfigure and recreate without payment to their former rights holders. But they’ve been sequestered for so long that their origins have been obscured, allowing the public to rediscover them anew.

Thanks to our convoluted copyright laws in the U.S., the wait has been 95 years.

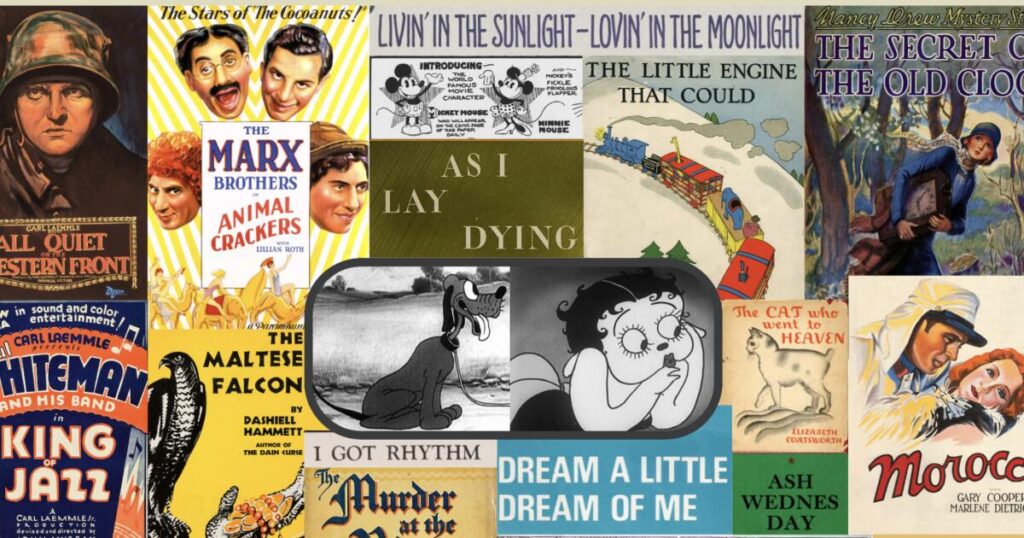

These characters aren’t the only artistic creations entering the public domain this year. As Jennifer Jenkins and James Boyle of Duke Law School report in their indispensable annual report about public domain day, the list includes Dashiell Hammett’s fully realized book version of “The Maltese Falcon” (perhaps better known through the 1941 Humphrey Bogart movie); Nancy Drew; Dick and Jane, those icons of reading instruction through the 1970s; the Gershwin brothers’ song “I Got Rhythm”; the Marx Brothers’ second full-length film, “Animal Crackers”; and The Little Engine that Could.

Before we explore the consequences of the long wait for copyright expiration, here are the answers to the above quiz:

1. Dagwood Bumstead was the scion of a rich family that disowned him when he married Blondie, a flapper — forcing him to take an office job under the irascible J.C. Dithers. 2. Blondie’s maiden name was Boopadoop. 3. Betty Boop was a dog.

Those characters have been part of America’s cultural heritage almost since their first appearance — the Blondie comic strip still runs daily in The Times, and Betty Boop’s image is widely and popularly merchandised.

Why the long wait? Blame commercial interests, including the Walt Disney Co., which agitated for the long term chiefly to maintain control of Mickey Mouse for as long as possible. (Mickey entered the public domain in 2024, which was 95 years after his first appearance in the 1928 short “Steamboat Willie.”)

Congress has gifted those commercial actors with repeated copyright extensions. The initial copyright act, passed in 1790, provided for a term of 28 years including a 14-year renewal. In 1909 that was extended to 56 years including a 28-year renewal.

In 1976 the term for material owned by their creators or heirs was changed to the creator’s life plus 50 years. In 1998, Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, which is known as the Sonny Bono Act after its chief promoter on Capitol Hill. That law extended the basic term to life plus 70 years; works for hire (in which a third party owns the rights to a creative work), pseudonymous and anonymous works were protected for 95 years from first publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter.

Along the way Congress extended copyright protection from written works to movies, recordings, performances and ultimately to almost all works, both published and unpublished.

The extensions were rationalized by the theory that creators (or their heirs) should be entitled to income from a work well into the distant future in order to incentivize artists to create.

But that’s a category error. In truth the income stream from all but a tiny minority of published works largely disappears after a few years, and what does arrive decades in the future has a minuscule present value at the time of creation. The 20-year extension in the 1998 law, as 17 economists (including five Nobel laureates) wrote in a 2002 Supreme Court brief, provided “no significant incentive to create new works” and arguably less for existing works. The beneficiaries of the extended term generally are businesses that desire not to create something new, but to keep exploiting old content that still produces a strong revenue stream (i.e., Mickey Mouse).

There’s something to be said for the virtue of relegating important works to a period of obscurity to turbo-charge the excitement of rediscovery. But not much, and especially only after a wait of 95 years.

Duke’s Jenkins refers to “the harm of the long term — so many works could have been rediscovered earlier.” Moreover, she says, “so many works don’t make it out of obscurity.” The long consignment to the wilderness thwarts “preservation, access, education, creative reuse, scholarship, etc., when most of the works are out of circulation and not benefiting any rights holders.”

Among other drawbacks, she notes, “films have disintegrated because preservationists can’t digitize them.” Many films from the 1930s are theoretically available to the public domain now, but not really because they’ve been lost forever.

What would be the right length of time? “We could have that same experience after a much shorter term,” Jenkins told me. “Looking back at works from the ‘70s and ‘80s has similar excitement for me.” Economic models, she adds, have placed the optimal term at about 35 years.

It’s proper to note that just because something is scheduled to enter the public domain, that doesn’t mean legal wrangling over its copyright protection is settled.

With recurring characters, for instance, only the version appearing in a given threshold year enters the public domain 95 years later; subsequent alternations or enhancements retain protection until their term is up. That has led to courthouse disputes over just what changes are significant enough to retain copyright for those changes.

“Copyrightable aspects of a character’s evolution that appear in later, still-protected works may remain off-limits until those later works themselves expire,” Los Angeles copyright lawyer Aaron Moss said. That aspect of copyright law engendered a lengthy dispute waged by the estate of Arthur Conan Doyle against creative artists wishing to put Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson into new works.

Holmes and Watson first appeared in the novel “A Study in Scarlet,” published in 1887, but the estate attempted to block an anthology of Holmes stories by outside authors planned for 2013. Its argument was that it retained the rights to the characters as long as any of Conan Doyle’s novels or stories remained under copyright, which wouldn’t expire until 2023. A federal judge threw out that argument in 2014; in 2023 the estate’s claim breathed its last breath, and Holmes and Watson indisputably belonged to the public.

That brings us to the case of Betty Boop, which may occupy the copyright bar for years to come.

The argument for Betty’s entry into the public domain stems from her initial appearance in a short titled “Dizzy Dishes,” by the brilliant animator Max Fleischer and his brother Dave.

The Fleischers and Disney were contemporaries, but the resemblance ends there. Their animation techniques were utterly different, as was their character.

“Broadly speaking, there was an innocence in Disney’s view of the world, while Fleischer projected an underlying kinkiness,” Charles Silver, the film curator at the Museum of Modern Art, wrote in 2011. “Although the films were shown to all audiences, one can’t escape the feeling that Disney saw his audience as children while Fleischer’s target was more knowing adults, attuned to Betty Boop’s seductiveness.”

Fleischer Studios went out of business in 1946. By then it had sold the rights to its cartoons and the Betty Boop character. A new Fleischer Studios was formed in the 1970s by Fleischer descendants, including Max’s grandson Mark Fleischer, and set about repurchasing the rights that had been sold.

Whether it reacquired the rights to Betty Boop is up for discussion. (The controversy doesn’t involve Fleischer’s trademark rights in Betty Boop, which are separate from copyrights and bars anyone from using the character in a way that suggests they represent Fleischer.)

According to a federal appeals court ruling in 2011, the answer is no. Having navigated its way through the three or four copyright transfers that followed the original rights sale, the appeals court concluded that the original Fleischer studios sold the rights to Betty Boop and the related cartoons to Paramount in 1941 but couldn’t verify that the rights to the character had been sold in an unbroken chain placing them with the new studio.

The “chain of title” was broken, the appellate judges found — but they didn’t say who ended up with Betty Boop. The Fleischers maintain that they own the Betty Boop rights through “several different chains of title, which we believe are all valid,” Mark Fleischer says.

What about the Betty Boop of “Dizzy Dishes,” which is indisputably entering the public domain in 2026? Mark Fleischer told me the Betty Boop-like character in that short may be in the public domain but “is not the Betty Boop we know today.”

In a “fact check” posted on its website, Fleischer Studios states bluntly that the idea that Betty Boop is entering the public domain is “actually not true.”

Yet the character in “Dizzy Dishes” certainly looks and sounds a lot like the Betty Boop we know today. She’s a flapper with a short skirt and spit-curled coif, the facial structure of Betty Boop, speaks with the high-pitched voice of Betty Boop and utters the catchphrase “boop-boop-ba-doop” (which was identified with a popular singer of the period). But she also has a few canine characteristics that soon disappeared — chiefly flapping dog ears, which morphed into hoop earrings by 1932.

It’s hard not to see the strong resemblance between the 1930 version and later incarnations; indeed, on a Fleischer Studios web page tracking the evolution of Betty Boop in illustrations, the very first entry is the “Dizzy Dishes” character.

Fleischer says his company hasn’t sued purported copyright infringers since the appellate case, though it has “contacted one or two” to explain its position “and we’ll see how they respond.” But he says he wouldn’t be surprised to see that some people will accept the assumption that Betty Boop enters the public domain next year without delving into the legal technicalities.

Jenkins maintains that the copyright protection given to post-1930 depictions of Betty doesn’t extend to “‘merely trivial’ or stereotypical modifications of Boop 1.0, such as replacing the dog ears with human ones, [or] dressing her in standard attire for a cabaret performer or homemaker.” Whether that’s the case might have to await further court rulings, if purported infringers appear.

In the meantime we still have a treasure trove of indisputably copyright-free creations — William Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying”; Evelyn Waugh’s second novel, “Vile Bodies”; and the songs “Dream a Little Dream of Me,” “Body and Soul” and “Georgia on My Mind,” among much, much more. Enjoy.

The post Blondie and Dagwood are entering the public domain, but Betty Boop still may be trapped in copyright jail appeared first on Los Angeles Times.