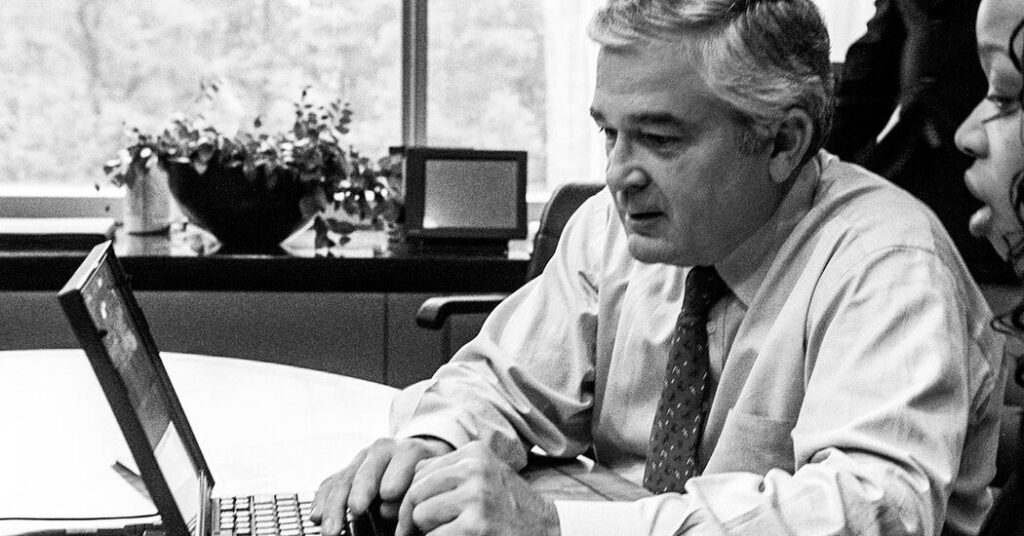

Louis V. Gerstner Jr., an outsider who became the leader of IBM when that giant computer company was in a tailspin, and who engineered a remarkable revival of its fortunes in the 1990s, died on Saturday in Jupiter, Fla. He was 83.

His death, in a hospital, was confirmed by Kara Klein, the executive director of Gerstner Philanthropies, the family’s charitable foundation. The family did not disclose the cause of death, she said. Mr. Gerstner lived in Hobe Sound, Fla., north of Jupiter.

Mr. Gerstner became chief executive of IBM in 1993, and his selection was a sign of the company’s deep troubles. Arriving from RJR Nabisco, where he had been chief executive, he was the first IBM leader to be recruited from outside the company’s ranks since it was founded in 1911.

By the early 1990s, the mainframe era of computing that IBM had dominated was in eclipse. The technology of personal computing, with its low-cost hardware and software, was taking over the industry, led by Microsoft and Intel, and was extending to larger machines in data centers.

That shift hit IBM hard, and its mainframe revenue was plummeting. Predictions of IBM’s demise were commonplace in magazines and books.

When Mr. Gerstner arrived at IBM’s headquarters in Armonk, N.Y., in Westchester County, and examined the company’s finances, he was alarmed. Listing his immediate challenges, he wrote at the top: “Stop hemorrhaging cash,” as he recalled in a 2002 memoir, “Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? Inside IBM’s Historic Turnaround.” “We were precariously close to running out of money,” he wrote.

He quickly slashed costs and the work force. He traveled the globe to reassure skittish corporate and government customers, and ordered senior executives to do the same. He shook up the culture of a company that had become mired in bureaucracy and slow-motion decision-making. Long meetings with elaborate presentations were replaced by short reports and candid conversations.

Mr. Gerstner shifted IBM’s focus, making it less on hardware and more on consulting and services, helping customers use technology effectively rather than just selling them products. He oversaw the overhaul of its mainframes to run on lower-cost chip technology, stabilizing that crucial business.

With the internet beginning to take off, Mr. Gerstner positioned IBM as a trusted partner to companies that were uncertainly embracing the new online technology.

Mr. Gerstner’s moves steadied the company and led to IBM’s revival in the 1990s. During his tenure as chief executive, which ended in 2002, IBM’s stock market value rose nearly sixfold.

“Lou Gerstner saved IBM,” David Yoffie, a professor at the Harvard Business School, said in an interview.

Shortly after he took the IBM job, Mr. Gerstner was asked about his vision for the company. He replied tersely, “The last thing IBM needs right now is a vision.”

The remark was greeted with a chorus of scorn in Silicon Valley, seen as proof that Mr. Gerstner had no technical vision for IBM’s future and thus was likely to fail.

The comment, he explained later, was meant to communicate that IBM had more immediate problems at the time in just trying to stay afloat.

Mr. Gerstner was an outsider to the technology industry. When he came to IBM, he was generally regarded as a management gun for hire. His résumé included American Express and McKinsey, the management and consulting company, as well as RJR Nabisco.

One widely held view was that he had been brought in to oversee the breakup of the company. The theory was that the spun-off pieces of IBM would be more valuable than the whole and the best deal for shareholders.

There was, in fact, a breakup plan on the table. In his book, Mr. Gerstner described investment bankers “scrambling over most parts of the company, dollar signs in their eyes.”

But after early customer visits and a trip to IBM’s research lab, Mr. Gerstner came to the conclusion that keeping IBM intact, as a supplier of both products and know-how, potentially offered a distinct advantage. “Keeping IBM together was the first strategic decision and, I believe, the most important decision I ever made,” he wrote.

In a letter to IBM employees on Sunday, Arvind Krishna, IBM’s current chief executive, echoed that view, writing, “Lou made what may have been the most consequential decision in IBM’s modern history: to keep IBM together.”

If not a technology visionary, Mr. Gerstner nonetheless had a clear plan for the best way forward for the company. “Lou Gerstner came to technology from a customer’s point of view partly because he had been a technology customer at his previous companies,” Michael Cusumano, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management, said. “He thought the one-stop shop was good for customers, and it often was.”

Much has changed at IBM in the more than two decades since Mr. Gerstner retired. Today, the term “big tech company” is used to refer to Google, Microsoft and Nvidia rather than IBM. But while it is smaller, IBM is still a sizable corporation: It generated more than $60 billion in revenue last year and has about 270,000 employees worldwide. Its current focus is helping other companies adopt cloud computing and artificial intelligence technology, and it’s a leading investor in the emerging field of quantum computing.

“Solving hard problems for businesses has been IBM’s strength over the years, and Gerstner really emphasized that,” Mr. Cusumano, of M.I.T., said.

Louis Vincent Gerstner Jr. was born on March 1, 1942, in Mineola, N.Y., on Long Island, the second of four sons of Marjorie and Louis Gerstner Sr. His father was a dispatcher for the F. & M. Schaefer Brewing Company, and his mother was an administrator at a community college.

Education was highly valued in the Gerstner household. “My parents remortgaged their house every four years to pay for schooling,” he wrote in his 2002 book.

He was on a fast-track to success in school and at work. He went to Chaminade High School, a Roman Catholic school, in Mineola. His undergraduate degree was in engineering science, from Dartmouth College, and he went to Harvard Business School for an M.B.A. Fresh from Harvard, he joined McKinsey & Company at 23. He rose to become partner at 28 and senior partner at 31.

In 1977, Mr. Gerstner left McKinsey to join his largest client, American Express, to head its credit card and traveler’s check businesses. He stayed at American Express for 11 years as the business grew and flourished. While there, he developed “a sense of the strategic value of information technology,” he recalled in his book, as the credit card operation was essentially “a gigantic e-business,” though no one used that term in those pre-internet days.

Mr. Gerstner was tapped to become the chief executive of RJR Nabisco in 1989. It was essentially a slash-and-cleanup assignment after the company had been the object of a furious bidding contest at the end of the leveraged-buyout boom of the 1980s — a corporate battle that was the subject of the best-selling book “Barbarians at the Gate.”

The winning bidder was the investment firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, and RJR Nabisco became a private company saddled with a mountain of debt. The leveraged-buyout bubble burst shortly after, “sending a tidal wave of trouble over the deal,” Mr. Gerstner wrote in his book.

To make debt payments, billions of dollars of assets were sold. By 1992, despite all the cost-cutting, it was apparent that the financial returns on the deal would not meet expectations. “It was clear to me that KKR was headed for the exit, so it made sense for me to do the same,” Mr. Gerstner wrote.

He is survived by his wife, Robin (Link) Gerstner; his daughter, Dr. Elizabeth Gerstner, a clinical neuro-oncologist at the Mass General Brigham Cancer Institute in Boston; and four grandchildren. His son, Louis Gerstner III, died in 2013 at 41 after a choking incident in a restaurant.

Gerstner Philanthropies, founded in 1989, has made grants totaling more than $300 million in four areas: biomedical research, environment, education and short-term financial assistance to prevent homelessness. Support for medical research included the creation of the Gerstner Sloan Kettering Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences in Manhattan in 2004.

The financial assistance program, called Helping Hands, is an effort to prevent homelessness with emergency grants so that, for example, caring for an ill child, which reduces work hours, does not lead to eviction and homelessness.

Last year, Helping Hands rent grants, typically made through social service organizations, went to more than 5,700 households — about 1,000 more than the previous year. The grants average $1,350 a household. Roughly 95 percent of grant recipients who responded to outreach are stably housed a year later, the organization said.

In an essay in The Wall Street Journal two years ago, Mr. Gerstner described such programs as “the least expensive policy interventions for preventing homelessness.”

“Now, more than ever,” he wrote, “we need others to join us in this effort.”

Steve Lohr writes about technology and its impact on the economy, jobs and the workplace.

The post Louis V. Gerstner, Who Revived a Faltering IBM in the ’90s, Dies at 83 appeared first on New York Times.